45 years since their eviction from their island home by the USA and Britain

It's been 45 years since the forced eviction of the Chagossian people from their island in the Indian Ocean, to make way for a military base; time has done nothing to suppress their desire for justice, and the right to return to their homeland. The Chagos islands are situated in the Indian Ocean, about 500 kilometers south of the Maldives. Their plight reflects the worldwide struggles for human rights and speaks out against land dispossession, which remain as real today as they were for South Africans pre-1994.

Let Us Return - The Story of the Chagos Islanders - 2015 from Evoque on Vimeo.

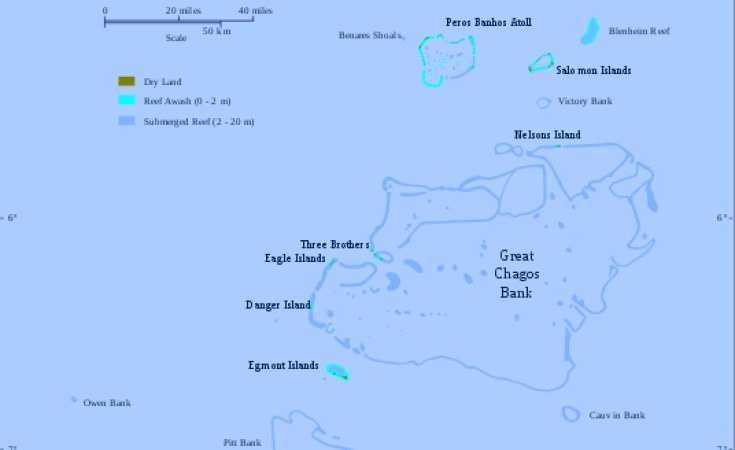

The Chagos Islands look like the kind of blue ocean paradise destinations advertised in travel magazines. Otherwise known as Chagossian Archipelago, it is made up of no less than 60 exquisite tropical islands. It is situated in the Indian Ocean between Madagascar and the Indian subcontinent, and despite its beauty, it has a bitter history of displacement and despair. After five decades, the people of the island are still fighting for the return of their land.

During the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War, the American navy travelled the Indian Ocean in search of an island to build a military base. The largest of the Chagos Islands, Diego Garcia (which spans 33km²), was selected for this purpose, and the 2000 inhabitants were deported from the island by the British government in order to make way for the American base.

Those who remember the deportations recall being escorted off the islands, forced to leave their belongings behind and shoved onto ships, never to see their home again. "When we were deported, we were taken with a stick at our back, put on a boat" said one man, who was a young boy at the time of the deportations.

"As we were deported, our animals and dogs were killed," said another inhabitant. "And we were taken out of the island like animals ourselves."

The British have kept the story of the islands complex, confusing and hidden from public scrutiny but the fact of the matter is that one of the most powerful known empires has wilfully suppressed the most basic right, the right to land, in the full glare of the international community and international law. Before the rule book on geo-political pragmatism and international stability is thrown at us, let's consider the facts.

The sovereignty of the islands has long been disputed, primarily between the United Kingdom (UK) and Mauritius. In arrangements dating back to 1814 between France and the UK, Mauritius and the Chagos Islands were considered a single entity, even until the United Nation's (UN) proclamations on decolonisation in the 1960s, which required that the entire Chagos Islands and Mauritius be decolonised, with sovereign ownership of the entire complex, including Diego Garcia, accruing to Mauritius.

This position is also currently advanced by none other than pre-eminent International Law and Human Rights Law expert, Sir Geoffrey Robertson. The long legal battles fought within the British and European courts have not resolved the matter one way or the other. However, the Chagossian leadership are still hopeful that victory will be achieved.

The dispute is rooted in the twin issues of the act of independence, itself, granted by the United Kingdom to Mauritius in 1968, and the simultaneous act on the part of the United Kingdom not to relinquish control over the Chagos Islands, which is a case of colonialism continued, to this very day.

At the centre of the UK's intransigence in this matter sits the island of Diego Garcia and the off-the-table negotiations between, on the one hand, key persons within the UK Harold Wilson Labour Government (circa. 1967-1970), and on the other, the Lyndon Johnson [US] administration (November 1963 - January 1969). In essence, and at the height of Cold War paranoia, the United States of America negotiated a lease with the UK government for the Chagos Islands, subject to the following conditions. Firstly, that the Chagos Islands be extricated or disentangled from any rights of control which may have accrued to Mauritius over the islands following it gaining independence and secondly, that the islands be offered to the United States free of any Chagossians. In exchange for the government of the UK being able to deliver on these conditions, it would receive from the USA a set of premium Polaris missiles valued at £14 Million, without a cent being exchanged across the pond, thus rendering any inquiry or ratification by the US Congress or Senate or the British Parliament as being surplus to requirements. The path was now clear for another chapter in the growing global militarisation which has characterised the last 35 years of international politics and International Law.

Caught in this muffled Cold War crossfire played out over one of the most idyllic and pristine suburbs of this universe we find 2 000 Chagossians whose roots on the island can be traced back 200 years. The United Kingdom opted for the first and easiest resolution to the vexed problem as to what to do with 2000 human beings who had gotten in the way of a key strategic location for military expansion. In 1971, the Chagossian were hurriedly alienated from their place of birth and summarily shipped off to Mauritius and the Seychelles. Although many later took up residence in England, the Chagossian diaspora has remained in unison throughout regarding their right of return not being denied.

What followed the 1971 forced exodus of the Chagossian people from their homeland was a complex web of political and legal wrangling on the part of the United Kingdom to ensure that it holds on to the islands in order to honour its lease arrangements with the United States, and to ensure its continued place within the Axis-of-Empire.

To its credit, the African Union were unambiguous in their condemnation of the actions of the United Kingdom on the Chagos Archipelago and called for the right of return of the Chagossians to the islands and for the sovereignty of the archipelago, undivided, to return to Mauritius. The AU Resolution [AU25/2005] was clear on its call for Diego Garcia to remain a part of the Chagos Archipelago and held that this position was in keeping with International Law, which required that territory previously colonised, cannot be divided, with separate portions held onto by the coloniser, prior to the act of official decolonisation.

One need not have to be a scholar of history or international law to grasp the nettle here; that the simplest, most elementary and yet pivotal principle of International Law which screams out from this case is that the strength of the law is derived from it being applicable to all peoples everywhere. The application of this principle almost immediately demystifies many of the battles for territorial sovereignty and human rights which prevail today; the case of Palestine not being excluded.

Alongside this universal rule on sovereignty must stand the concomitant rule on the right of return.

Whilst much has been said and written on the plight of the Chagossian people, the risk of the issue going to ground is a real one. Although it is now almost a given that the renewal of the lease of the islands to America, which comes up for official renewal in December 2016, will be a formality, it does nothing for the reinstatement of the rights of the dispossessed. The Chagossian people, who have been remarkably resilient in pursuing their end goal, declared that they are not principally opposed to the continuation of the US military base at Diego Garcia, but that they simply wish to have their right of return reserved, to be exercised as they wish.

This cause, alongside others of the kind, must be popularised and brought into the public realm and into the public conscience. This violence has continued for far too long. The UK simply needs to do the right thing and negotiate in good faith for the return of the Chagossian people to the land from which they were exiled. The manner in which this case is resolved or lost forever will determine which of the forces ultimately triumphs; the influence of military might, or the strength and efficacy of the international legal system.

For thousands of South Africans the experience of land dispossession is all too familiar. No South African can claim not to have been affected by this, not even the beneficiaries of what was the systemic dispossession of land from many for the benefit of a few; an injustice which we still skirt around to this day. South Africans don't have to try hard to understand this reality, land dispossession is a part of our history and current social fabric, which makes South Africa's silence on the case of the Chagos Islands all the more conspicuous and puzzling.

As glorious as Shakespearean literature may be, we needn't have to quote the 'journeys end' extract from Twelfth Night to understand that, to most, us and the Chagossians no different; life's 'journeys end' is with those we love dearly, in the land we love completely.