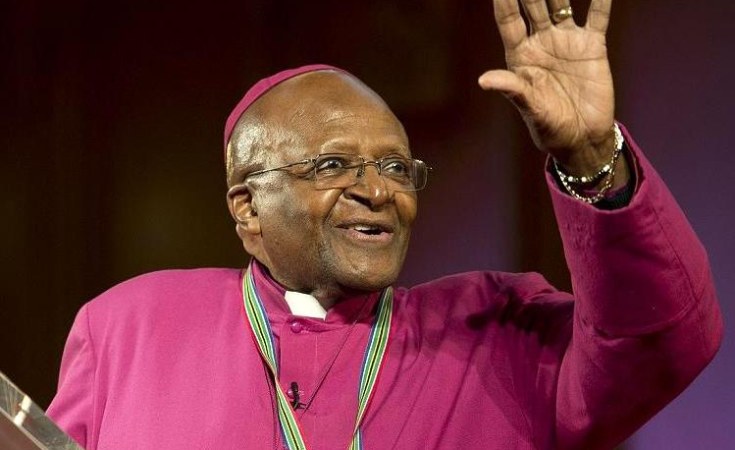

Washington, DC — Last month, Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu turned 70, triggering a flood of congratulations from around the globe.

The son of a schoolteacher and a domestic worker, he joined the priesthood only after starting life as a teacher.

In 1976, in the wake of the uprising by young black South Africans, Tutu was appointed General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches (SACC) and became a nationally and internationally known campaigner against apartheid, eventually being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

In 1985, he was elected Bishop of Johannesburg and a year later, Archbishop of Cape Town, where he was a thorn in the side of the National Party regime in Pretoria and a powerful advocate for change. It finally came in 1990 when President F.W. De Klerk unbanned the ANC and the Communist Party and opened the way to negotiations about a transfer of political power.

A year after the country's first democratic election in 1994, President Mandela asked Archbishop Tutu to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and investigate human rights violations under apartheid. Archbishop Tutu and his fellow Commissioners presented the TRC's report in October 1998, after hearing three gruelling years of testimony.

He retired as Archbishop of Cape Town in June 1996, but was named Archbishop Emeritus from July 1996. There has been widespread anxiety about his health since he was diagnosed as having prostate cancer.

On October 31, 2001, Desmond Tutu delivered the second Oliver Tambo Lecture at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. It contained a powerful call for reconciliation and against revenge which many saw as a thinly-veiled critique of the US assault on Afghanistan. The philosophy of "an eye for an eye" could not achieve security, he said. "Violent reaction to the suicide bombers... just seems to give rise to further suicide bombers."

Akwe Amosu interviewed Archbishop Tutu the day after he spoke in Washington, DC. Excerpts:

Are we right to read your Georgetown speech as a suggestion to the US and the American people that they should reconsider the bombing campaign in Afghanistan?

Oh yes. I think so. I was hoping that, by being oblique, one would still be able - without making people too defensive - to begin to open up and try to look at the consequences of what were doing and why were doing it, to look at what were trying to achieve and whether it is achievable. For their own sakes, really.

Do you think that message will be heard in the right places?

(laughter) Well, you keep hoping that itll get through, but there is, at the moment, an almost obsessive demand that something must happen. And even if it isnt succeeding, that people should see that action is taking place.

Because I think that there is a sense of bewilderment amongst the people in this country. They have always been the ones who have been hitting out and it was something that was happening out there, thousands of miles away, with their smart bombs, often with very few American casualties. So they had this distance. And they also had, I think, a very deep sense of security which turns out, in fact, to have been false.

They are not yet able to understand how a defence system that is so sophisticated, so expensive, could have been rendered so thoroughly obsolete [by the events of September 11] and useless to defend them. They cant quite understand that yet, not surprisingly, I dont think. If youve always been the top dog, and suddenly you discover, "Hey, Im just like any other human being. We are like any other human society. Were vulnerable. Vulnerable."

Whats the worst thing that could happen if this message doesnt get heard?

Well, one of the things is what it will do to the American people. Which is that they might want to turn a blind eye to something that they know is wrong. And that will erode their true greatness. And in a way, I think one has to say, look, this is a remarkable community of people. They are a really good, really generous, caring people. And yet, in an odd kind of way, theyre also a vindictive people. I mean when you look at how they still hold on to capital punishment, when it is abandoned in so many places. I mean America could not become a member of the European Union. They would be disqualified because they still support capital punishment. They are, as it were, subverting the possibilities of true greatness. And the reaction from the world will be the sort of thing that makes September the 11th possible.

There is an anger, a resentment in the rest of the world, especially in the so-called Third World, that the United States can support whoever they want to support, if, at that time, it is in their so-called national interest. They have tended to support despots, people whose human rights record is appalling. I mean, when you consider that Osama bin Laden is really a creature of the United States, something they maybe do not want to face up to. Think of whats happened with Contras in Nicaragua, with Savimbi in Angola, with Marcos in the Philippines; you can go on and on like that and it is worrisome. It is worrisome that they can have seemed so reckless about the consequences of their policies for other people. And one is saying, please, please, for your own sakes - and of course for the sake of the rest of the world - reconsider, reappraise, what you are about.

Moving away from Afghanistan now, to South Africa, your own country. I know that youre deeply concerned about the problem of poverty in South Africa today and, in fact, youve recently said that if the gap between the rich and the poor is not closed, we can "kiss reconciliation goodbye". Is South Africa's transition really as vulnerable as that?

Well, it is not just an unreasonable idea that comes from Archbishop Desmond Tutu; it was contained as one of major recommendations of our five-volume report of the TRC, that reconciliation means that those who have been on the underside of history must see that there is a qualitative difference between repression and freedom.

And for them, freedom translates into having a supply of clean water, having electricity on tap; being able to live in a decent home and have a good job; to be able to send your children to school and to have accessible health care. I mean, whats the point of having made this transition if the quality of life of these people is not enhanced and improved? If not, the vote is useless.

So how do you explain, that seven years on, this is the situation were faced with?

In part, I think weve had a failure of leadership on the part of the white community where, you would have hoped that many of the leaders would have said, "hey, were very, very fortunate. We have people on the other side who could so easily have gone on the rampage, and destroyed everything that we have. They havent done so. They have been patient seven years."

I mean, I am, myself, still very, very, very amazed that people can show that kind of patience. But weve already seen what could be warning lights with the land invasions. I mean, it may be copycatting the things in Zimbabwe, but I dont think so. I think that there are people who are beginning to say, "whats the point?"

But are you right to place the blame at the door of the white leadership? I mean, youve got an ANC government which has a huge majority, which many other governments would love to have, and support from all over the world for the transition. Surely, tackling poverty is a job for the government?

Well, you can distribute resources only if you have resources. Im not exonerating the government from all blame, but I still believe that it would have been far better for the acts of generosity to emanate from those who have benefited from apartheid for all these years and who still own a big share of the resources. I mean when you look at the Stock Exchange, only maybe about 10% has changed hands.

You know, it's possible for the government to pass legislation and therefore force people to do what is in their own interests. But it would be better if they were to say, we really do want to see transformation happen, we are ready to do as much as we can, voluntarily; because you dont want to build up resentment in them. Because you are trying to create a new kind of society, a new kind of people, not a situation where this has to happen because the law says it has to happen. Theres got to be a generosity in response to the magnanimity that came from the other side. Thats the idealistic view.

But you know, some people would say: "Look, the government started out right; they said they were going to follow the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which was specifically designed to give the poor a new start; but then they abandoned it and adopted what even the South African Council of Churches leadership has described as a kind of homegrown structural adjustment program that could have been created by the World Bank." (laughter) So many would say that the government has set the example.

Well, we mustnt be too harsh on them because I think, for one thing, weve forgotten that were talking about people who, apart from having never voted at all, had no experience of government. And weve got to take our hats off to them, that we have been able to maintain the kind of stability that we have.

I mean there are things like the supply of water to so many people who previously didnt have it and the housing units... I mean Im not too enamored with what they have built, but they have built probably about a million, or something like that. There are some achievements to their credit. But they are also struggling in this globalised economy. To try to reassure foreign investors that we are not just spendthrift socialists, as people have feared. And it may be that they have bent over too far backwards in trying to reassure foreign investors, at the expense of maybe some real intervention by the public sector, where they could have justified a great deal more public spending on so many projects that would have benefited the people. And yes, they leave themselves open, to some extent. Their fiscal policies, their military policies, are perhaps far too stringent.

But the RDP is apparently making a kind of comeback. The Black Empowerment Commission Report publicised a few months ago looks very like the old RDP...

I havent seen that. But you know, part of the reason why one has been making the plea for the 'Marshall Plan' kind of strategy is that it is actually a bit much to expect this new democratic government to deal with a quite horrendous legacy left behind by apartheid, and, equally, to be trying to modernize, to do the things that a government should be doing, without worrying about the backlog. I think it is a bit unfair. (laughter)

So tell me about the Marshall Plan idea. What does it consist of?

Well, as you can realize, Im not an economist. Im not too smart with figures. I thought that it would be peanuts for the United States to give us two billion dollars - not for keeps - say, over a five year period. They could put down very strong, stringent conditions of what it should be spent on - maybe housing, education, health, releasing, therefore, what the government would be spending on these things, to do other things. You see, its not just South Africa that was devastated, but Namibia, the Frontline states, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Zambia and all those places. And it ends up being very enlightened self-interest. Because if you are able then to get those economies vibrant, Voila! You may be able to open a market for western economies. And when there is a relative measure of prosperity, you know that its more likely that area will be stable. And this spin-off is tremendous. Because it is a lot easier to promote democracy and good governance in a situation where there is relative prosperity.

Have you had any kind of response, any kind of government or corporate reaction, to this proposal?

Well, when I first floated the idea, I did meet up with some people from Congress - members of the Black Congressional Caucus, one or two senators. And I was actually quite surprised at how warmly they responded to it; but of course this was pre-September the 11th. They were very supportive. And didnt shoot it down, I mean as something that wouldnt even reach first base. I spoke to one or two prime ministers in Europe. And again, they werent saying, "Oh, this is an outlandish, bizarre idea." They thought there was merit.

Let me ask you about Aids. We read a lot of terrible stories about HIV/Aids in South Africa. Is it really as bad as they suggest?

Its very bad. Its quite shattering. I mean, when you look at the obituary notices in newspapers, the Sowetan publishes a list of obituary notices every Friday and its quite amazing. My wife is not ghoulish, but she likes looking at it because you get to hear about people that you know. What is now note-worthy is, how young the deceased are. Increasingly, it's young people. And they cant all be dying from TB or something like this. It is devastating and there is no doubt at all, that unless there is a very significant and decisive intervention, were going to be decimated.

The church has put itself right at the forefront of the fight against Aids with the trade unions and other elements of civil society. Is that the right place for the church to be and what should it be doing?

Well they were in the forefront in the struggle for freedom. And its the same kind of justification that the Gospel speaks about, the issues that are important to people. Health is important to people. Good life is important to people. Our faith is not one that says, "Were going to have to wait for pie in the sky, by and by, kind of thing." Human life in the 'here and now' is of very great concern to God. And I mean, our Lord could have very well told people, who came, who were sick, "dont worry. Youll have a wonderful time in heaven." He spent time healing them. And when they were hungry, he spent time feeding them. And thats the mandate for the church. And Im very thrilled that my successor as Archbishop is way out there in front and really giving outstanding leadership in a very critical, actually catastrophic - thing that is facing us.

There appears to be a deep division and ambivalence within the foremost ranks of the South African government about tackling this problem head on. Whats going wrong?

Were spending far too much time that we cant afford, in academic discussions about what causes Aids - is it this or that? And I think that its something that we should please desist from. We cant afford to be fiddling, as our particular Rome burns.

But what seems to be happening is that the lack of leadership is filtering further down through the ranks and showing up in some very immoderate language. For example, the ANC in KwaZulu accused the head of the South African Council of Churches of being an agent of the pharmaceutical companies because he had said that anti-retroviral treatments should be available.

Well, I dont want to be involved in all the mud-slinging. But Im just saying that we ought to acknowledge that were facing a very, very serious challenge and that we ought to stop playing marbles. People are dying.

It is possible - the evidence is there - for the lives of people to be extended; for the quality of life to improve, once they have been diagnosed as having Aids. Through being given the right kind of drugs; that seems to be incontrovertible. And for goodness sake, let's try to use the methods that have been tried and found to be reasonably effective. There is no cure as yet, but we are aware that you can make a very significant difference if you tackle the thing head on.

Leaving the government aside, which obstacle is the biggest? Is it that people just dont want to talk about the realities of whats going on, or that people just dont want to talk about sex?

That used to be the case, but I dont think that it is any longer. I mean there are still people who may be in denial, but I believe, that in the overall, people are saying, we are facing a massive challenge. We really ought to get our act together, and the new alliance between the churches and the trade unions gives very considerable cause for hope.

Even the government will realize that they cant just dismiss people as being irresponsible, because I dont think the Archbishop of Cape Town would want to be associated with something that was not a serious venture.

Finally, I know youre always so modest, but I think you know that youre very loved all over the world. And the main question most people would ask is, how are you? Hows your health and are you making your way out of your illness?

People are very, very good and many have prayed for me. I sometimes say, half facetiously, that God must have been saying, "Oh dear, not all these many prayers for this one man? The best way to deal with this thing is to make him better!" So Im better. And I want to say a very big 'thank you' to everybody who has been praying for me, and thank you to people who have provided me with medical care.

Thank you very much indeed.

God bless you. Thank you.