Kampala — DISAPPOINTED. That is how Henry Kyemba felt on receiving the news that his former boss, Idi Amin, was dead. Disappointed that Amin passed away without being tried for the numerous crimes he committed while head of state.

"He has cheated us all," lamented Kyemba during an interview with The New Vision. "Now we have to mourn him, and sympathise with his family and friends, as dictated by African culture."

The retired senior civil servant turned politician served as Private Personal Secretary, Permanent Secretary and later cabinet minister in Amin's regime, before fleeing into exile in 1977. That is after receiving an unsigned handwritten note warning him that his life was in danger.

The warning marked the end of a long-surviving relationship between the two men that started in the 50s, when Kyemba was still a student and Amin a junior officer in the King's African Rifles (KAR) headquartered in Jinja.

Kyemba's older brother Kisajja and Amin were dating sisters; Mariam and Mary, both sisters of Wanume Kibedi.

Amin went on to marry Mariam, while Kisajja had a child with Mary. Technically, the two men were Basangi (marrying from the family), according to African culture. Ironically Kisajja, who was NYTIL Jinja personnel manager, was one of the first victims of Amin's regime.

He was abducted and eventually killed in 1972, on the same day as the Chief Justice, Ben Kiwanuka.

On graduating from Makerere University, Kyemba joined the Prime Minister's office as assistant secretary in charge of protocol and ceremonials. His work, which involved liaising with state house, foreign affairs ministry, police and the army, kept him in constant touch with Amin, then a senior officer in the KAR. "We would meet to discuss things like troop colours, while preparing for public functions," recalls Kyemba.

Kyemba was flying home with Obote from a Commonwealth Summit in Singapore in 1971, when news of Amin's coup reached them. After a short spell in exile with Obote in Tanzania, Kyemba returned home to Uganda, where Amin was the new head of state. Amin ordered the retired civil servant to immediately report back to his office and continue with his duties.

Before the coup, Kyemba had been working in the President's office as Principal Private Secretary. So he continued in that capacity until Amin made him Permanent Secretary, and eventually cabinet minister.

As someone who worked closely with Amin right from his salad days, Kyemba strongly believes the dictator who is credited with 500,000 deaths was a creation of the very same people who are now busy condemning him.

A British trained career army officer, Amin originally had never dreamt of becoming a head of state, let alone life president.

His British mentors in the KAR had drilled into him the belief that a soldier's life was in the barracks, and it had sunk in well. So when he promised to hand over power to civilian rule within a short time, during his inaugural public address, he meant it.

According to Kyemba, Amin grabbed power to save his skin, which Obote was determined to have at all cost.

Obote was already in the process of stripping Amin of his powers as army commander, so that he could be prosecuted for the numerous crimes he had committed over the years.

Amin took advantage of Obote's many weaknesses, the main one being his attempt to divide the army along tribal lines, to sway the disgruntled soldiers to his side, and eventually use them to overthrow his boss.

Amin's strategy was to take over power and hand it over to a more "understanding" person, then fade back into military uniform. "At first Amin was convinced the presidential boots were rather too big for him, and most of us agreed with him. Personally I never expected him to survive beyond two weeks." Explains Kyemba, who is convinced that it is the public's warm reception, which gave Amin the confidence to hang on to power.

Instead of questioning his unconstitutional actions, and lack of basic qualifications to head a state, people just treated Amin like a hero who had saved them from Obote's dictatorship.

In Ankole, he was given 10,000 heads of cattle, in Buganda he was given a wife, all in appreciation of his "heroic act." It was at this point that, according to Kyemba, the-chair-is-sweet syndrome started setting in. That is when Amin started getting ideas, and started bumping off people who threatened his hold on power.

Ben Kiwanuka and hundreds of army officers hailing from Obote's home area were killed, in response to the 1972 aborted invasion from Tanzania.

Kyemba believes this failure by Ugandans to stand up to the dictator right at the beginning, is another factor that gave Amin the green light to step up on his brutality.

"People (Ugandans) would rather die in sequence than die collectively, which suits a dictator like Amin just fine," argues Kyemba, who studied the history of world politics, to come to that conclusion.

Instead, as people kept on disappearing one after the other, the survivors just looked on and waited for their turn, which was not long in coming.

When he finally fled into exile, Kyemba had problems explaining to the puzzled western world, how Amin could kill half a million people, and the rest of the population, just look on.

Kyemba further argues that Amin was also able to get away with the numerous atrocities he committed, because of his deceptive character. "Amin had this posture of a simple and friendly person, that is why he was so popular with the ordinary people, especially the ladies."

Kyemba analyses the character of a man often described as the "gentle giant." An accomplished sportsman, a keen cultural dancer, a smart soldier, it was just impossible to resist Amin's charm.

That is the image Amin beamed out to the world, both at home and abroad. But behind the picture of a benevolent leader and man of the people, lurked a ruthless mind, with an overdeveloped sense of self-preservation. He was the kind of man who would dance with you in the evening, and have you bumped off in the morning.

To avoid getting caught on the wrong foot, people who interacted closely with Amin needed to master the art of monitoring his erratic mood swings, just like Kyemba did.

"I could easily tell his mood, from the way he started his conversation, especially on phone." Kyemba shares the tricks that helped him survive Amin for five years; "If he opened the conversation with the words; You see... I would straight away conclude the man was very angry, and I would immediately regret picking the phone."

When in a light mood, Amin would switch to Luganda with words like Owange, okola ki? (Hey buddy, what are you up to?)

Such a call would come dead in the night, when most normal people are already asleep. Amin would then burst out laughing at the polite answer of: I was sleeping your excellence. He would eventually conclude the conversation with a lewd comment like olowooza simanyi ky'okola (You think I don't know what you are doing?)

While Kyemba agrees Amin was generally a bad ruler, he insists not every negative thing that has been written about the late dictator is true.

"The attitude of most people is that with Amin anything goes, which is sad," laments Kyemba. "The truth about Amin is bad enough, so there is no need for exaggeration."

Amin's alleged craving for human flesh is one example.

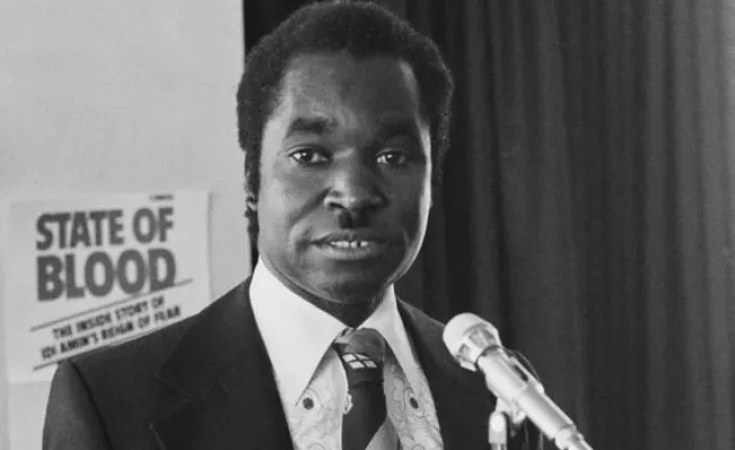

Although in his book State of Blood, Kyemba quotes Amin describing the taste of human flesh as very salty, the former health minister dismisses the stories of Amin's cannibalism as old wives' tales.

"I would have known," he insists. He says he had many friends among people who worked closely with Amin, and they would certainly have informed him about Amin's unusual preference for human hamburgers. At least they informed him in time, when Amin decided it was Kyemba's turn to feed the crocodiles.

Although he lists his late older brother Kisajja among Amin's victims, Kyemba highly doubts if the former head of state really had a hand in the abduction and murder of his Musangi. Kyemba suspects several of Amin's top henchmen, who once worked as labourers in NYTIL, with Kisajja as their boss. That is before Amin came into power, and they fell into things.

Kisajja may have slighted one of them, or they just wanted him out of the way, so they could replace him with someone who would favour their kinsmen.

Even after the death of his brother, Kyemba decided to continue serving in Amin's government, a decision that earned him a lot of criticism.

According to Kyemba, circumstances forced him to stay behind, when most of the country's elite class were fleeing into exile. "During Amin's time, it was not possible to resign, and stay in the country," he says.

Kyemba was also reluctant to leave behind his elderly mother who lived with him, and to whom he was deeply attached. In the end, it is the old woman who made the decision on Kyemba's behalf, following the murder of Archbishop Janan Luwum and two cabinet ministers.

Taking advantage of his position as chairman of African health ministers, Kyemba travelled to Geneva for a World Health Organisation (WHO) summit.

Kyemba had sought and received clearance from Amin to travel to Geneva, and even instructed him to lobby hard for an African to become the next Director General of WHO.

But just to ensure that Kyemba returns home after the summit, Amin had the minister's wife and her sister detained in Gadaffi army barracks in Jinja, while soldiers were posted at his residence.

When Kyemba called the president to brief him about the summit, Amin feigned ignorance about the detention of the minister's wife and her sister. "I knew he was lying." To throw his boss off his guard, Kyemba kept on calling Amin to update him about his progress at the summit.

Amin eventually released Kyemba's wife and her sister, and also withdrew the soldiers from the minister's home. With help from influential friends, Kyemba managed to smuggle his family out of the country into Kenya, and eventually to join him in London.

Today, Kyemba , who is currently doing voluntary work with Rotary International, is not surprised that while some Ugandans are mourning, others are celebrating his demise.

In order to please some people, Amin had to annoy so many others. Those who benefited from his rule are justified to mourn his death, just like those who lost their loved ones during his regime are justified to celebrate his death.