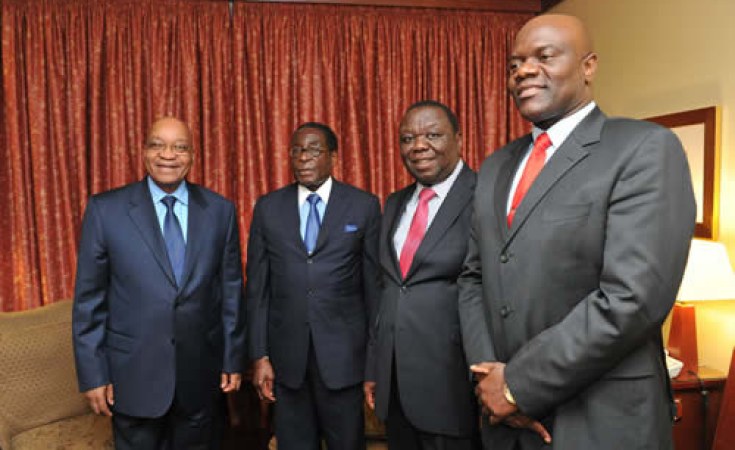

As leaders of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) meet in Johannesburg this weekend in yet another attempt to resolve the Zimbabwe crisis, the question remains whether a credible election is possible without concrete steps to end ongoing human rights violations.

Until March 31, when the SADC Organ Troika on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation categorically acknowledged the "resurgence of violence, arrests and intimidation in Zimbabwe" it was doubtful whether SADC had the political will to speak out against human rights abuses.

The regional bloc seemed oblivious to the arbitrary arrests, malicious prosecutions, torture and other blatant violations of human rights afflicting the country.

Any durable solution for Zimbabwe will need to place respect for human rights at its heart, and SADC will need to speak out strongly when these rights are violated. President Robert Mugabe and his Zanu-PF party are effectively in control of the police, army and other state institutions which violate human rights. Despite the formation of a multi-party Government of National Unity more than two years ago, the president has done little to ensure that those institutions respect the rights enshrined in the country's own constitution and in the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights.

This weekend, behind the closed doors of the extraordinary summit, SADC leaders will presumably hear Zanu-PF accusing Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai's Movement for Democratic Change (MDC-T) of committing violence, with some evidence compiled by the police to support this argument. They will hear claims that the troika's condemnation in March was based on false information. MDC activists are not all saints: in recent weeks, particularly in the run-up to the party's congress in April, members were involved in intra-party violence, for which they should be held accountable.

Prime Minister Tsvangirai and his party will presumably also tell the SADC leaders of the malicious prosecutions of members of his party, including the arrest of senior members serving in the unity government. He may also talk about vilification of his party in state media. He might report on the threats and intimidation which members of his party face in rural areas and how, paradoxically, police often arrest the victims of violence, rather than the perpetrators (usually Zanu-PF supporters).

However, the SADC leaders may not hear that which is most important: the voice of ordinary Zimbabweans. They need to hear of the suffering that the unresolved contestation of political power has caused to ordinary people.

They need to know about the 17-year-old boy who was beaten on May 20 by police trying to force him to disclose the telephone number of a leader of the social justice movement, Women of Zimbabwe Arise (WOZA). The boy was arrested by the Law and Order Section of the Zimbabwe Republic Police's Criminal Investigation Department after they failed to locate his mother, who is a member of WOZA.

Six WOZA activists arrested around the same time spent five nights in police cells. Their lawyers told the courts that the women had been denied food and access to the lawyers. Police also verbally abused them, calling them prostitutes. Even more seriously, police threatened them with death and enforced disappearance. The women's "crime" is that they engage in peaceful action drawing attention to lack of clean water, exorbitant electricity bills and the high cost of food, health care and other basic services.

SADC leaders need to hear about the 45 social justice activists arrested in February when they attended a discussion of events in North Africa. They were charged with treason and were at risk of being sentenced to death if convicted. Thirty-nine were acquitted because the court found they had no case to answer. The remaining six still face charges of subverting the constitution, though the treason charges have been dropped.

The list of human rights violations against perceived opponents of President Mugabe's party is long. It includes the arrests of actors for producing a play calling on the government to address rights violations during the state-sponsored violence around the 2008 elections; the arrest and prosecution of a Facebook user for posting a comment on the Prime Minister's website; and the arrests of human rights workers for facilitating meetings with victims of violence.

Most Zimbabweans are afraid that the country could slide back to the levels of violence witnessed in 2008 simply because little, if anything, has been done to implement fundamental issues identified for reform - including human rights training for the police, army and other state institutions - in the Global Political Agreement (GPA) which established the unity government.

In their deliberations on the road map to elections, SADC leaders need to look beyond the immediate political objective of securing an accord between Zanu-PF and the MDC-T. An accord will not end the human rights crisis in Zimbabwe and will certainly not result in an undisputed election. SADC must insist that President Mugabe and Prime Minister Tsvangirai take clear steps within their parties and government to address the legacy of impunity for human rights abuses.

SADC's reputation is at stake as the guarantor of the GPA. As the region's leaders meet in Johannesburg, will they act impartially and stand on the side of victims of human rights violations? Or will they allow themselves to be talked into issuing another hollow statement that perpetuates a climate of fear in Zimbabwe?

Michelle Kagari is the Africa deputy programme director of Amnesty International.