Washington, DC — In three years, Samasource has paid more than U.S.$1.5 million in real wages to over 2,000 trained workers in places where most people survive on less than $3 a day. The social enterprise links major technology companies with people living in poverty. In particular, Samasource provides women and youth with the skills and resources to deliver digital services to companies in the United States and abroad.

The San Francisco-based company was started three years ago by Leila Janah and has completed over six million tasks for clients in an effort to combat the almost 70 percent unemployment rate faced by people living in impoverished countries. After accepting the Innovation Award for the Empowerment of Women and Girls, sponsored by the U.S. State Department and the Rockefeller Foundation in March, Janah sat down with AllAfrica's Trevor Ballantyne to tell the Samasource story, and to discuss the impact of empowering people through employment.

You traveled to Ghana when you were 17, and you say that was a defining moment for you. What did you experience there that inspired you?

I had a scholarship from a tobacco company for $10,000. I was one of those nerdy Indian kids who applied for every scholarship, and so I got this one and I felt kind of weird using tobacco money to go to college.

I also wanted to have an adventure so I left Los Angeles and volunteered through the American Field Service for this school for blind kids in Ghana, about two hours north of Accra, in a town called Akropong.

When I got there I thought I was going to be this 'American who saved the day' and teach these poor desperate children English and give them some basic skills so they could survive in the world. But then I discovered that all of my students were really bright. They could name U.S. senators that my high school classmates couldn't name because they listened to the BBC and Voice of America radio, and they were just incredibly bright and talented.

I ended up designing a creative writing class for them. They were just so hungry for knowledge, and it kind of broke my heart because I think there is this myth that poor people are somehow incapable and that they are just these charity cases. But then you meet people and you realize that they could all easily be flourishing if they had a fraction of the opportunities that we have. If my students had the same chance to attend good American public schools the way that my brother and I did, their lives would be so different. That really profoundly impacted me, and I began thinking about how we could change this situation and allow these people to use their capabilities to be productive in the global economy.

It seemed like the biggest problem was there weren't any jobs in Ghana. So even if you are really bright and motivated, and worked really hard, there is just no way to get any employment that would cover your cost of living. That is why so many really smart, educated people from developing countries come [to the U.S.] and they end up being taxi drivers, or they come here and take on lower wage work because they are just so desperate for employment.

Some time later, I stumbled into the outsourcing sector as a consultant, and had this ah-ha moment one day where I said, 'If you can take this work, that is all done through the Internet, and transport it to very poor communities, you could create a way for them to generate cash, just with the brain power that is already there.'

We have already invested so much in educating the world's poor, and then these people go through secondary school, they graduate and there is nothing for them to do. And to me that is the most dangerous situation - a large number of unemployed young people who are completely aware of what they're missing. So Samasource's goal is to bring employment to as many of them as possible through digital work.

In your opinion, what does Samasource do well compared to other capacity building initiatives?

Well, I should say that we are only three years old, and there are many other organizations that probably do a much better job than we do across the board. But I think one of the reasons that people are probably interested in our model is that we are harnessing this new form of work, digital work. We call it micro work because we actually divide the work into really small units.

We think micro work is to outsourcing what micro finance is to banking. The idea is that you can take this thing that was only done with middle class or rich people and you can break it down so that you can really bring opportunity to people who would otherwise be overlooked by the sector. This is exactly what micro finance did for banking; it exposed the world to this new constituency that had previously been written-off. Micro work does the same thing for workers who are in really poor places.

I think what is innovative about our model is that we are using the Internet to distribute work and to pay people, which has really only been made possible in the last couple of years, when mobile payments, increased Internet access and low cost computing hardware is now proliferating. So I think we have a lot to learn, and there are many amazing organizations that have worked on this issue of work force development or job creation, but I think we do bring something new to the table that is cool to share.

So how did you find your first employees?

It's a great story. I was in Kenya in 2007 on vacation with a Kenyan friend of mine. He comes from a great family - his father is a dean at a big university. Now I am one of those people who after a day at the beach I need to do something - I need to read, I have to meet some people. So I was talking to his dad and I said that I had this idea of bringing outsourcing work to Kenya, and hiring really poor people from slums and rural areas to do it. In Kenya you meet young guys on the street who speak beautiful English, who might be hawking newspapers to earn a dollar a day. My friend's father loved the idea. He took me to meet this business incubator called Enablis. So I go there and I said that I have this crazy idea, and they said, 'We love crazy ideas, come on in.'

I asked if they could bring me entrepreneurs who run Internet cafes or data entry firms, or basically mom-and-pop shops that have Internet access and computers so I could see if this idea makes sense. And Enablis brought 80 people to me, and we had a day-long focus group.

Bitange Ndemo, who is the ICT minister of Kenya, showed up and it turned into this big to-do, but really it was just a conversation, and I said, 'Hey, can you guys do this work?' At the time I thought it would just be HTML coding or graphic design, that sort of thing, all the way down to really basic data entry.

One of the people in that audience was Steve Muthai who was 25 at the time, my age, and I was really inspired by him. He was a serious entrepreneur and he was just really restless, and wanted to grow his company. He had four people who were doing data entry, graphic design and running an Internet cafe. And he told me that it's really hard to run an Internet business in Kenya because everyone makes roughly two dollars a day, so there is not a huge number of people that can pay retail prices for Internet usage.

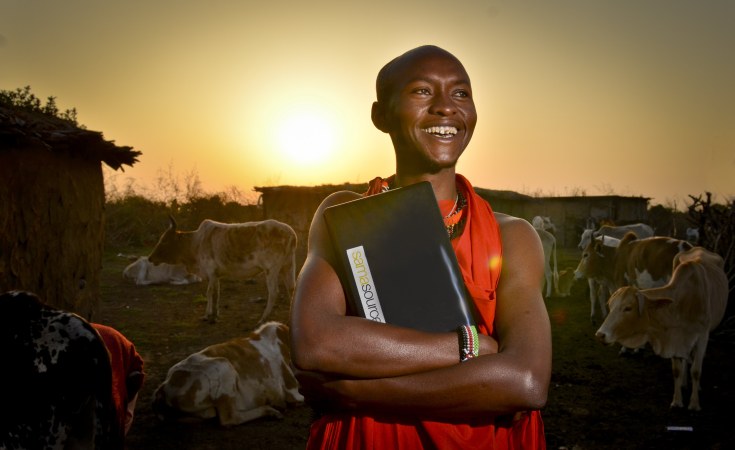

But if you take that capacity that Steve has already built and you turn that into a revenue generator for that community, all of a sudden that becomes a viable business. So we like to say, 'The laptop is the new sewing machine.' I love that because really it's just latent capacity.

So Steve became our first partner in Kenya, and now he has grown his company to over 150 people all doing Samasource work, and his sister has joined the network as an entrepreneur. So that is kind of how it got started and then through word of mouth.

Now we have a network of 16 entrepreneurs in six countries who do this work in Kenya, Uganda and South Africa. And we have paid and trained over 2,000 people and about 51 percent of our workforce is women.

We are trying to find ways to make it easier for women to work, things like offering child care, it is really inexpensive to have a person sitting in a room next to the tech center who can watch the kids for the women who are in the tech center. It adds marginally to our cost, but think about the benefit - if a woman can come to work with her kids, leave them right there and visit them throughout the day. Because our work is unitized it really permits frequent breaks, so someone can do micro tasks for an hour, then go say hi to her kids, then come back and do some more work. But the real win for us would be if women could do this work from their homes.

How have you seen your work impact women's lives and the communities they live in?

Deeply. There is one woman in particular who I just met the last time I visited, named Jacqueline. She is 25 and has three sisters, and grew up living in poverty with a single mom. Jacqueline is so smart; she studied computer hardware in vocational school before she had to drop out because she couldn't pay her fees. Then she got a job at Steve's center in Nairobi, and she started making so much money that she was able to send her sisters to school, pay part of her mom's rent and save for her own education. Then she got poached after seven or eight months to work in a computer store where she fixes computers. So it is a really cool story.

So what we strive to do is be a bridge, a bridge for people who often don't see themselves as formal workers, or as capable or worth the investment of a company's time. And what is so cool for someone like Jacqueline is that we have done work for major companies such as Linkedin, and our employees know that. It is extremely empowering to feel like: 'I am contributing data to this company in Silicon Valley on the other side of the world, and this company values me enough to pay me for what I am doing.'

This is especially important for a women from a poor community who has probably been told by the world around her - maybe not explicitly but certainly implicitly - that she is not really capable and she is not really a producer and at best she can receive a handout. So for that person to feel like she's a producer and that she is being taken seriously in the real economy, by a really big company, is a huge deal.