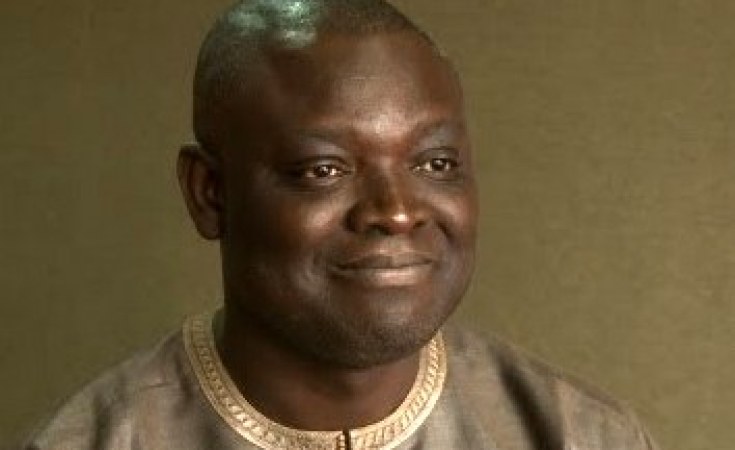

An agriculture economist by training, Mamadou Biteye has worked in many parts of Africa for organizations as diverse as the African Development Foundation, Oxfam and the World Conservation Union. He holds two Masters degrees and a Bachelor of Science and speaks five languages. As managing director for Africa at the Rockefeller Foundation, he oversees Africa-wide initiatives from the foundation's regional office in Nairobi, Kenya. He spoke to AllAfrica about the foundation at 100.

The Rockefeller Foundation has been observing its centennial year. Would you talk a bit about what the aim of 'promoting the well being of humanity' means for a century-old institution?

In 1913 John D. Rockefeller defined the mission for what would become the Rockefeller Foundation. That mission, which really is a timeless mission, is something the foundation has been working hard to implement but also has been revisiting occasionally - because the world we live in is a dynamic world. What 'promoting the well being of humanity' meant 100 years ago is different from what it means today.

In the run up to the centennial year, the foundation revisited or reinterpreted that mission to understand what it means in the world of the 21st century. Among the many global trends that we've looked at we've found that two were really overarching.

One was growing inequality - inequality between individuals, between communities, between countries, which leaves part of the world community vulnerable to being excluded from the global economy. That led the foundation to decide to elevate two goals.

One of them is building inclusive economies – looking at how we can make sure the benefits of globalization are shared. How can we multiply economic opportunities that would allow poorer and vulnerable people to access the resources, information, skills and partnerships they need to better realize their potential?

The second overarching change we have seen is the increasing vulnerability of people to shocks and stresses. If there is something that has been really constant during the past years, it's the multiplicity of shocks and stresses. Preparedness to these shocks is really important to increase people's well being.

A second goal - derived from the analysis of that second overarching theme - is building resilience. We define that as building the capacity of people, of communities and systems to anticipate and withstand shocks, but also to be able to emerge from those shocks even stronger.

Those are two goals the foundation is pursuing through its four areas of focus: advancing health, revaluing ecosystems, securing livelihoods, and transforming cities. These come from reevaluating our mission in the face of the changes and the dynamism of the 21st century.

Are there major challenges specific to Africa in pursuing the Rockefeller Foundation's goals of promoting economic inclusiveness and resilience – or is every country around the world different? In other words, are there particular regional challenges to advancing those goals in Africa?

I think Africa is in a unique position, although the issue of building inclusive economies is really a global challenge. Almost everywhere in the world, a small portion of the population owns a lion's share the resources.

Around the world, countries have been challenged to recover from the 2007- 2008 global economic and financial crisis. Africa is no exception to that.

The particular challenge for Africa is that by and large it is still registering high growth rates. The story of Africa's growth is everywhere. Yet much of the African population is not experiencing the benefits of that growth. It is not translating directly to their pockets or to their table. It is really important to address that in Africa.

If you also look at the issue of stresses and shocks, we can see that most African countries are ill prepared to face those stresses because of lack of comprehensive planning - and with a resilience lens.

The 100 Resilient Cities challenge, whose 2014 round of winners will be announced 3 December – how does that fit with the priorities and concerns of the Foundation?

Africa has seen the fastest urbanization, with challenges of congestion, infrastructure, service delivery, security, vulnerability and growth of slums. 100 Resilient Cities is an opportunity for Africans to rethink cities, not just in terms of urban development, but with the goal of developing cities with the ability to be resilient. When we talk about resilience, it's not just in the face of natural disasters. It is important that African look at different dimensions, whether it is social resilience, economic resilience, or infrastructure to manage natural disasters.

Only two of the 33 cities selected in the first round were African.

During the first year of the challenge in 2013, we received a respectable number of applications from African cities. These applications were different from cities from around the world, because in Africa we still think of cities in terms of urban planning and development rather than really bringing the lens of 'resilience to shocks'.

However I have to say that there were a couple of very good, very thoughtful applications. In the first batch of 33 cities, two African cities submitted extremely high-quality applications and were selected. These cities are Durban in South Africa, and Dakkar in Senegal.

We learned a lot as a foundation by analyzing all of the applications we received from throughout the world. Naturally the team worked to incorporate lessons learned into the 2014 challenge. Questions were different, things that cities had to prepare were more to the point. We tried to mobilize global partners to create awareness with African cities but also linked them with relevant capacities to support them in preparing their applications.

For the second round, what did you do to encourage more and stronger applications from Africa?

The resilience effort is really a collaborative effort. It's not just the responsibility of municipal authorities. Of course, they should be leading, but it also involves other government entities. When you think about it, municipalities have just a few devolved responsibilities. Many of the responsibilities or sectors that are required in building resilience skills sit in central governments.

It also requires the input of populations who actually face the challenges, moving rapidly, on a day to day basis – the private sector, civil society organizations and others to bring the diversity and multiplicity of points of view to make these resilience plans much more comprehensive. That's what was done to improve the quality of the African cities applications.

We have learned a lot and will continue to learn in this process. It will continue for three years, so every year we can improve on the challenge process and make it much more collaborative and much more targeted.

Selected cities get funding to hire a 'resilience officer', as well as assistance and tools to help implement their resilience strategies. Is working with cities to build more resilience in some way a form of impact investing?

Not really. Impact investing is looking at addressing market failures and specific problems, related to our issue areas. It helps corporate and individual investors to really think about the 'double bottom line'- which is maximizing shareholder benefit while at the same time having a social impact. That work is still continuing through the platform we've supported, which is the Global Impact Investing Network. It promotes the adoption of impact investing by more and more corporates globally.

The 100 Resilient cities will look at having a good plan, a plan that is comprehensive, a plan that looks at development, but also looks at resilience in ways reduce the risks of cities – and of borrowing, because they become better credit risks. This plan is going to support cities in raising and leveraging the billions of dollars of funds they will need to invest in infrastructure, whether it's physical infrastructure, or social infrastructure or economic infrastructure. We're working together with the World Bank to build credit worthiness of cities. This project is designed to also link cities to eventual investors so cities can raise those resources.

Job creation, the digital economy, climate change – these also are continuing Rockefeller themes for your second century?

Absolutely! When you think about social resilience, it's actually making sure that all groups in a population or society are included.

Today we have a big issue with youth and women being mostly excluded from the economy. Today youth in most African countries represent most of the population, yet the opportunities for them are very, very few.

This is why we launched 'Digital Jobs Africa' last year, with the goal of impacting the lives of one million people in six African countries. This means creating about 250,000 jobs in these countries. We have different pathways to job creation: one is in collaboration with the private sector; another is with governments.

The nature of the jobs we are looking at are more in service provision, outsource services and other types of services. So we are working with corporates so we can have impact sourcing. Impact sourcing is something that we define as a socially responsibly arm of the private sector to provide employment opportunities to young people who otherwise would be unable to access the job market. That is really the social impact.

Like impact investing, that makes perfect business sense for the companies in terms of reducing costs but retaining high quality of performance. At the same time, these corporates would be able to have social impact in a way that is more powerful than just corporate social responsibility.

The second stream of work is partnering training institutions to provide the prerequisite skills to young people who are highly talented, but socially and economically disadvantaged, which keeps them out of the market. These are essentially what we call personal skills. We try to work with these training institutions to create curriculum that will allow them to provide demand-led training - training these young people to the specifications and needs of the private sector.

The third theme is working with governments and other institutions to create an enabling environment to increase investments in the digital sector, in the ICT sector to create those jobs – and, at the same time, to mainstream such training through the national education systems.

One of the biggest problems that everyone raises in Africa is that the education system doesn't always produce the type of skills that corporations and other employers need. This approach is bridging the gap.

In the face of all these challenges you've mentioned – and many we haven't discussed, including health and food security. Are you still optimistic about Africa's future?

Yes, absolutely. I'm one of the Afro-optimists, because I think that Africa is set on the path to development. We have resources - natural resources, but also human resources. We are seeing increasing democracy. We are still challenged in terms of really good government and issues of corruption and inclusiveness. Today you have more highly educated populations that are able to hold their governments accountable. We have the vision, we have the confidence, and we have the resources to make it happen. Yes, I am absolutely optimistic.