"What we're doing matters," says Jeannine Mabunda Lioko Mudiayi, the personal representative of President Joseph Kabila of the Democratic Republic of Congo on sexual violence and the recruitment of child soldiers. Appointed in July 2014, she has pursued strengthening the justice system and has "sought to tackle issues of impunity and accountability, both in the military and in society as a whole". A 2011 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that women were being raped at the rate of 48 per hour, especially in militia-plagued eastern Congo, which created a culture of impunity that has persisted even though the conflict has lessened somewhat . Mabunda has set a goal of ending her country's reputation, as 'the rape capital of the world' – not through public relations but through transforming reality.

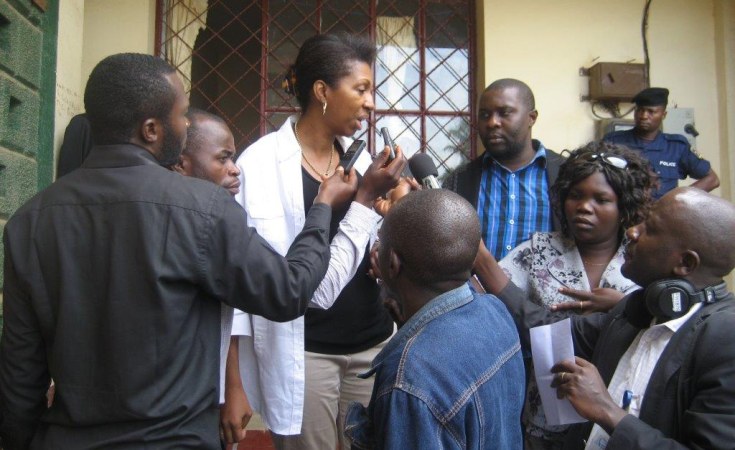

As one step in that process, her office launched a campaign to bring the issue of violence against women into the open. In a conversation with AllAfrica following her attendance at the screening of the prize-winning film The Man Who Mends Women at the United Nations last month, Mabunda discussed the challenges and the promise of her campaign to combat rape.

Breaking the silence

We started the Break the Silence campaign to educate people about the existence of laws which protect women. We wanted to inspire people and show them that the government of Congo is working to protect women from rape. We wanted to let people know that they have a tool, they have a weapon – and that weapon is the law.

We originally started this campaign in March. It was a challenge because we had no dedicated budget. At that time my office wasn't even a year old, so when I went to people and said that I wanted to initiate this campaign, they were quite skeptical.

The governor of Kinshasa (Congo's capital) decided to give us billboards for Break the Silence for free. He wanted to show that Congolese men are interested in changing the narrative and in changing the reality on the ground. The campaign brought a lot of success. We were concerned about budget constraints, but we received a lot of feedback, letters, phone calls, and text messages, mainly from young people at universities. We decided that this was a good test project, but recognized that the DRC is much bigger than Kinshasa.

The second phase of the campaign just started in September. We were very happy when UN Women and UNFPA (the United Nations Population Fund) decided to join the government in this campaign.

We started in Kinshasa, but this time we're also using flyers, posters, t-shirts and whistles, using the whistle to denounce rapists. We went to areas where people are more vulnerable – where it was normal for a 40 year old man to date a 15 year old girl. By law, sexual relations between the two is considered rape. People were very surprised, because by culture and by habit, they didn't know that this is considered rape. Not only is there rape when there is no consent, but there is rape when an adult has a sexual relationship with someone who is under the age of 18. We hope that parents will be encouraged to keep their daughters in school, knowing that this law is in place to help protect them.

Running out of T-shirts

For the new campaign, we're expanding outside of Kinshasa to Bukavu and Goma [in eastern Congo). Depending on logistical challenges, we hope to be able to reach all provinces in the DRC by the middle of next year.

All people have the right to be informed that sexual violence isn't acceptable, and they have a right to know that they can denounce it. A surprise from this campaign has been all the posts on Facebook. We had a lot of people from the diaspora community that we didn't target for the campaign who wanted to participate in this national crusade through social media.

We have a t-shirt and posters that say "Say No to Rape", and we were very surprised to see that a lot of young Congolese people all over the world have taken pictures of themselves wearing these shirts, or standing in front of their posters and are sharing these pictures on social media.

It was so moving, and we have decided that we would like to make it even more viral. We created a Facebook page for this and over the course of three weeks we had received over 10,000 postings from people who are interested in the cause. And now we're running out of t-shirts! We've learned that people are prepared to break the silence, and that the Congolese want to come together to stop sexual violence.

We have many ambassadors, men, women, entire families and members of the diaspora who have all participated. This is good – it shows that people are prepared to stand up and to reaffirm that we do not want rape in our country.

Grateful for the work of 'the man who mends women' – and other committed doctors

A documentary about the work of Dr. Denis Mukwege at Panzi Hospital, where victims of sexual violence, including young children, are treated, was prohibited in Congo when it was released. Mabunda intervened, and the film was aired on national television before she traveled to New York for the film's showing at the United Nations. There were rumors that her visit was aimed at preventing the screening.

I was not at the UN to prevent any screening of the film. The UN would never be receptive to pressure to restrict freedom of expression in the first place. This is not realistic.

The real story is that there had been some divergence between the filmmaker and the Minister of Information. The Minister of Information was concerned that, in certain parts of the film, there were some misrepresentations and confusing pictures that gave the impression that the one to blame for rape in the DRC is the Congolese army. I've seen the film many times before I participated in the UN screening. I think there's only one small segment of the film, towards the beginning, that could possibly give this impression. The army has been fighting to protect and secure our frontiers for a decade from intrusions from neighboring countries. The people in eastern Congo have experienced several brutal intrusions, and this is a sensitive issue.

Aside from what is happening in the Kivus (provinces in Congo's east), the rest of the Congo is at peace. So people who are living in the rest of the DRC may question this image. Sexual violence is not exclusive to conflict, or to the military. I think this is the issue the Information Minister took with the film. But, I don't think this is something that should result in preventing the screening of the film in the DRC. The majority of the film goes in the same direction that public authority does. If we are united, we are stronger. If we work together, we are stronger in addressing the issue of sexual violence.

I admire out country's decision to allow the viewing of the film in the DRC. And I think that whether it's Dr. Mukwege, whether it's President Kabila, or whether it's the people of Congo who are supporting the Break the Silence Campaign, we all have the same goal. We needed someone to boost the dialogue between public officials and the filmmaker. I was there with two other colleagues from the Cabinet of the President because we want to engage in this dialogue. And because we want the conversation to be fair and open.

The initiative of the NGO is impressive and so is the work of Dr. Mukwege. We're grateful for the many years of work he has dedicated to the people of the Congo.

There are also other doctors, largely unknown, who are doing incredible work in the field. There are two female doctors based in Kinshasa, who also specialize in fistula surgery (repairing the catastrophic results of violent rape), who are doing great work.

My point is that we need more support and coordination to effectively address sexual violence in the DRC. My office tries to connect and unite people who are working toward a common goal and the same vision. This is one of the reasons why President Kabila decided to create my office. I hope my office can serve as a leader, especially when the dialogue becomes challenging. These are very emotionally charged issues. We have to be very determined – and yet very delicate – in dealing with different stakeholders. We have to allow the screening of the film, if we're going to break the silence. We want to educate people.

This film was broadcast on national television in the DRC. I know that, in the past, both Dr. Mukwege and several NGOs have said that they haven't felt supported by their nation or their public authorities. I would like to think of all of us as a soccer team. To be successful, and if we're going to beat sexual violence, we all have to work together in a coordinated manner. We need all eleven players. We're all on the same side. This is why I traveled to the UN. We have an opportunity, and we can't afford to poison the conversation.

Together we are stronger. There are 78 million people in the DRC, and women make up 52% of the population. There are men, like Dr. Mukwege and other leaders, who are supporting the cause of women, who are opening the space so that we can have conversations about rape. They are encouraging change so that we can defeat sexual violence. It's humbling. This will not change overnight, but what we're doing matters.