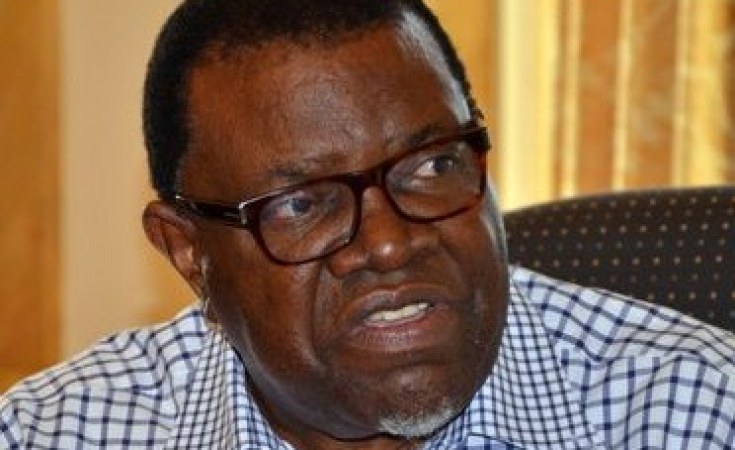

When Hage Geingob became Namibia's third president in March, he declared a 'war on poverty'. Since independence in 1990, the politically stable country has mended the rifts of conflict, held six successful national elections and invested in critical infrastructure. But despite strides in such areas as education and health care, the vast majority of its 2.2 million people remain poor. The minority white population of approximately 75,000 enjoys a high standard of living, as does a small black elite. Namibia's income inequality – one of the largest in the world – reflects a legacy of colonial rule, first by Germany and then by apartheid South Africa. He has appealed to the Namibian business community to support a 'solidarity wealth tax' on the most affluent citizens to be used for poverty eradication only.

Geingob was a leader of the Namibian independence struggle – led by Swapo, now the dominant political party – and has twice served as prime minister. He was elected president – the head of state - in November 2014 by an overwhelming margin. In an interview with AllAfrica's Tami Hultman and Reed Kramer , he said addressing economic inequality is both a moral imperative and a necessity for maintaining political and ethnic tranquility.

You were raised in the middle of the country. What was it like at that time?

The place where I was born is about 40 kilometers from Grootfontein. It's not a village or even a farm. It was a cattle post. From there we moved to where I grew up – on a farm owned by a German. The place had two names. Hereros called it Otjikururume and the Damara name was //Kharases – the two groups that live in central Namibia. It is interesting to note that all the German farmers in central Namibia spoke Herero or Damara fluently.

Keep up with the latest headlines on WhatsApp | LinkedIn

My first school was in Otavi [the district capital]. That school only went up to standard two [year four], so once I finished that I had to take correspondence classes. After standard five, I went to Augustineum College, a secondary school established by Lutheran missionaries. That's where many of us [who became Swapo leaders] met and where we were molded politically. That's where I first met people from the south and from the north, people like Theo-Ben Gurirab [Namibia's second prime minister] and Hidipo Hamutenya [a Swapo leader who briefly led an opposition party but recently returned to Swapo].

In 1962 a UN fact-finding mission was allowed [by South Africa] to enter South West Africa [as Namibia was known by the colonial rulers]. We went to the guesthouse where they were staying and demanded to present our views. We had a letter and gave it to them. After the mission left, I was summoned to the police station. Several of us were already planning to leave the country so we decided the time had come. In December 1962 we crossed the border into Botswana and I applied for a scholarship. It was tough times.

Jumping ahead to the present, how would you assess the progress made during 25 years of independence?

Nation building is not an easy thing. It takes long to mold different groupings into a nation. Americans are still struggling [with it]. So are many others. But we have laid a foundation - peace, unity and a democratic culture. We have held normal elections every five years, peacefully. We have had three changes in leadership. We also have good macro-economic management. Our banks are first class banks, our economy strong.

In our Swapo manifesto, we say President Nujoma brought peace and unity and President Pohamba stability. But people don't eat those things. It is my task to bring prosperity. Resource-wise, Africa is rich. Namibia is rich. But our people are poor. I have declared war on poverty. It's all-out war. We must address socioeconomic fundamentals.

No child should go hungry

One immediate problem we must address is hunger. No child should go hungry. We are creating a food bank with branches across the country. I have challenged commercial farmers to contribute – and they are eager, provided it is voluntary. We are asking the fishing industry and the private sector in general to help. We want to use government machinery - all the ministries must get involved. We are mainstreaming the fight against poverty.

Closely linked to poverty and inequality is the issue of land, which you said in your 100-days address, is a "crucial, delicate and emotive issue in Namibia." How are you addressing this and responding to critics like the Affirmative Repositioning Group, which has been protesting government policies?

Land is a big problem in all the former settler colonies - Zimbabwe, South Africa and Namibia. The problem is how to address this now while maintaining fair governance. When settlers came a hundred years ago, they stole the land. They didn't buy it. But their children were born here. Our requirement for citizenship is that you are born here. That determines your citizenship. We cannot kick out the white person who inherited the land from the father. But how about me? I was born on the white man's farm. We have to find a balance – meet half way.

We had a land conference that I chaired in 1991 where we deliberated all possibilities, including expropriation. The issue is complicated, and we couldn't solve it there. To whom does Namibian land belong? Who is the ethnic group that can claim to be the original owner of this land. That's where we got stuck. Perhaps the San – also called Bushman - can claim that. But all of us came here from somewhere. We couldn't identify the owner, so we shelved the idea of 'ancestral land' and said 'let's move on'.

We are committed to making our land productive and to affordable housing for all Namibians. This is complicated by the rise in the price of land. But the government has undertaken an urban land-clearing exercise, which ultimately should lead to more affordable houses for more people, especially at the lower income end of the market. That is why I have met with leaders of the Affirmative Repositioning Group to remind the young people that this is part of Swapo's manifesto. We don't disagree on this issue. We are disagreeing on modalities.

How are you approaching education and health, both closely tied to fighting poverty?

Health and education are priorities in Namibia. Education-for-all has always been our commitment, and we are among the few countries who spend a big chunk of our budget on education and health. We have praises for that. But do we get value for money? That is the problem. We are saying there must be accountability. Ministers must sign performance contracts and be accountable for what they do. I am accountable to the people who elected me and gave me five years. If I don't perform they could remove me, next election.

We handled malaria well. I think we are close to eliminating it. Where we are weak is infant mortality. We are declaring war on the high maternal and child death rate that afflicts so much of Africa.

How do assess the strength of democracy in Namibia after 25 years?

We have established electoral democracy. We now have to provide processes, systems and institutions to buttress that democracy.

We still see disputes in Africa after results are announced. Electoral commissions must be seen by everybody as independent and fair arbiters. So how do you do that? By making the electoral process fair and always transparent. Opposition party leaders must have confidence in the results the Electoral Commission pronounces, and they must accept the results.

In Namibia we are trying to do that. The electoral commission budget is coming directly from the Parliament. The posts are advertised and somebody qualified is appointed. It's not perfect, but we are working on it. We are the first to start using electronic voting. I got 87% [of votes] but nobody questioned it. That's a sign that our democracy is maturing. People complain, but they didn't question that I got those votes.

How has Namibia done on inclusiveness – making everyone feel that they participate equally?

We must not make anybody feel left out. We should be proud of our ethnic backgrounds, but we don't want any 'ism'. Tribalism is when you think your group is the most clever - only your girls are beautiful, only your people can be trusted in the security system. That is a problem we have avoided. If we are going by [ethnicity] certainly I wouldn't be president. But I got 87% of the votes. [President Geingob's Damara group is seven per cent of the population. The two previous presidents were from the Owambo group, which accounts for half the population.]

To be a leader, you have to be above those things. People must forget you belong to a tribe. You have to belong to all people. You are there as a servant. There must be trust, and trust can only develop if there is accountability and transparency. I declared my assets. I also declared my health status.

Do your ministers have to do the same?

Yeah, I required them to do it. We are now perfecting the forms to elicit more information.

To follow up on the inclusiveness issue, what about the role of women in Namibia.

I must give credit to President Pohamba. He was on the case. In the last Swapo Congress, we decided to seek 50-50 representation in party structures. In our National Assembly, we went from 24 percent of female representation to 47 percent - second only to Rwanda. We will achieve 50-50 very soon.

We give women very important Cabinet portfolios. I appointed the first female prime minister [Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila] and a deputy prime minister [Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah], who also has the very important portfolio of international relations and collaboration. We also have a women heading education [Katrina Hanse-Himarwa]. A dynamic women is heading our biggest ministry - Urban and Rural Development [Sophia Shaningwa].

You're challenging international donors and institutions on what you've said is the unfairness of categorizing Namibia as a 'middle income' country and reducing assistance on that basis. Why?

The global community takes the gross domestic product of our country and divides that by our small population to get a high per-capita income and therefore says we are a rich country. After independence, I was sent to argue to the World Bank that Namibia must be listed as a least-developed-country, but they refused. They said that's how they calculate it all over the world. They said our problem is distribution.

I asked them: 'If we grab from the white people and distribute to blacks, are you going to be happy? How do we re-distribute?' They didn't have an answer.

On our part, we have to recognize the reality that the majority of people in Namibia are poor. If we don't address that, the poor will rise up one day and all that we see as peaceful now will go up in flames. That's why we are declaring war on poverty and addressing that issue. We will do it. The mood is good in the country. People are joining the effort.