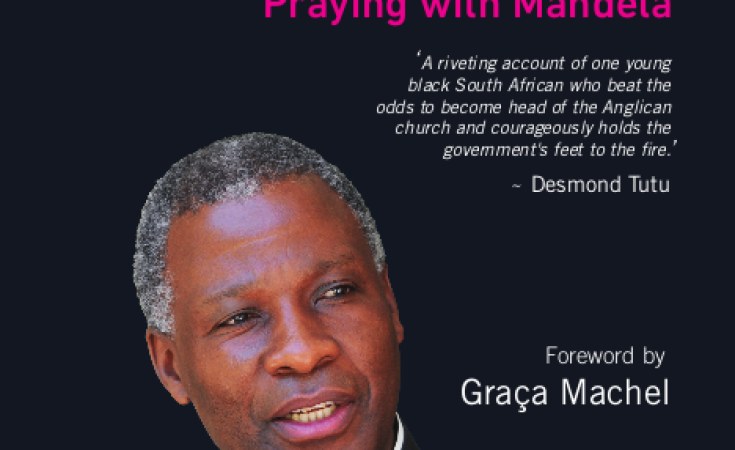

The former President of South Africa reflects on a memoir by Thabo Makgoba, head of the Anglican Church in Southern Africa, on his life and his ministry to Nelson Mandela in the last five years of Madiba's life. In his wide-ranging review of Faith & Courage: Praying with Mandela, Mbeki deploys quotations from a Papal encyclical, the Old Testament and Alfred Tennyson's poetry, and delivers an excoriating assessment of South Africa's current political leaders.

The author of this important book is a relatively young but eminent religious leader and theologian who is destined to continue to play an important role in the making of the new South Africa and Africa.

He is Archbishop Thabo Makgoba, Archbishop of Cape Town and Metropolitan of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa, who follows in the footsteps of such eminent predecessors as Archbishop Njongonkulu Ndungane and Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu.

As I considered how I could characterise the book, I thought that it might be appropriate to call it an Encyclical Letter because of the seminal messages it communicates. The reality however is that history seems to have reserved this particular identity, the Encyclical Letter, to the immensely important documents which are issued periodically by their Eminences the Popes of the Roman Catholic Church, Bishops of Rome and Sovereigns of the Vatican City.

In this context the Encyclical Letter has come to be understood particularly as a "circular" issued by His Eminence the Pope to the Bishops of the Roman Catholic Church, to communicate the views of this Church about various matters. Nevertheless it is true that through history, their Eminences the Popes have issued Encyclical Letters which have wider and global relevance.

The most recent is the Encyclical Letter, LAUDATO SI', issued in 2015 by His Eminence Pope Francis I, subtitled "On Care for our Common Home." To explain its purpose, this Encyclical Letter states, in its second paragraph:

"This sister (Mother Earth) now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her. We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will. The violence present in our hearts, wounded by sin, is also reflected in the symptoms of sickness evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life. This is why the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor; she 'groans in travail' (Rom 8:22). We have forgotten that we ourselves are dust of the earth (cf. Gen 2:7); our very bodies are made up of her elements, we breathe her air and we receive life and refreshment from her waters."

If we were to characterise this book as an Encyclical Letter, we would say that as indicated by its title, it is about "faith which cries out for the courage to stand up for what is right!"

This moving Makgoba Memoir perhaps best captures its own message in these words:

"How do we as a (Makgoba) clan deal with the pain we feel when we see the descendants of settlers, both British and Boer, prospering on our land? How do we look upon the modern-day Swazi nation, given the role some of their ancestors played in our defeat? How do we approach the role of the missionaries, who were in some cases chased out of the (Makgoba's) kloof, so unpopular did they become when they identified more with the settlers than with us. The pace at which we live, and the circumstances of our living in the modern world, leave very little space for healing. But South Africa's wounds are real and we must own them. We must stand in the gaps between feeling hopeless and hopeful, between being helpless and helpful, between hurting and being healed. My own spirituality has been nurtured and developed by the experience of hearing of the pain, fear, anger, resistance, but above all of the faith and courage of my forebears. It has given me a determination that wrongs must be righted, people treated with dignity and reconciliation achieved among the formerly oppressed and the former oppressor. In these endeavours, I believe the spirituality of Nelson Mandela, which I was privileged to experience during the closing years of his life, can help us find answers to the questions I have posed."

As I read the manuscript, it seemed to me that the memoir constitutes an outstanding testament to or affirmation of the continuing relevance of the wisdom contained especially in Chapter Three of the Book of Ecclesiastes in the Holy Bible. I refer here specifically to these extracts from this chapter:

"To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

"A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

"A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up...

"A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;...

"A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

"A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace...

"And moreover I saw under the sun the place of judgment, that wickedness was there; and the place of righteousness, that iniquity was there...

"Wherefore I perceive that there is nothing better, than that a man should rejoice in his own works, for that is his portion: for who shall bring him to see what shall be after him?"

Thabo Makgoba was born in 1960.

He begins his memoir by recounting elements of the history of the Makgoba clan as it lost its lands, in what is still called Makgoba's Kloof in the Limpopo Province of South Africa, through the brutal process of colonisation visited on his clan by the white European settler colonialists from about 1888.

Later, he discusses his interaction with Nelson Mandela, Madiba. This includes his direct participation in the processes in 2013 when the peoples of South Africa and the world joined hands in dignified and beautiful proceedings finally to consign Madiba to his final resting place, after his death.

And he does not stop there.

He goes on to speak about South Africa as it has evolved until the writing of his memoir in 2017, when its political leaders, the direct successors of Nelson Mandela, have, by acts of commission and omission, criminally deformed what Madiba stood and sacrificed for.

The deformed product which is then born is expressly contrary to the most fundamental interests of the people of South Africa and the legitimate expectations of the peoples of the rest of Africa and the world.

Here, in this memoir, are therefore the reflections and an account of a life of an African and a South African, still less than sixty years old, about a period which has helped to form him as a human being, covering 130 years.

It is an instructive kaleidoscope which tells a moving South African story about the complex process of the transition from an African clan late in the 19th century to the formation of a nation early in the 21st century.

That story is particularly moving because it is also objectively a truthful tale about the actions of a black South African, and the influences which impacted on him, as he migrated from being a mere member of a clan to a conscious architect of a new and diverse nation.

It is an account of how Thabo Makgoba, a direct product of the inhuman process of the merciless colonisation and racism of many centuries, starting in the 17th century, develops in the 21st to become a true, principled and steadfast leader in the historic endeavour to create a radically new social and ethical national reality, as a religious and moral beacon.

Surely it does not need any exceptional intelligence to understand that the very psychological development and being of such an individual would be formed by the historical and therefore objective reality, whether consciously understood or not, that"to every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven".

This memoir tells a graphic story of the seasons which helped to form Archbishop Makgoba and the purposes of the times through which he has lived. It is a story about how a young South African grew, evolved, matured and developed into the high position of Archbishop of Cape Town and Metropolitan bishop of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa.

This is a journey which saw him migrate from whatever little patch of land remained of his ancestral lands after the brutal process of colonial land dispossession, to grow up in the urban African townships of Alexandra and Pimville in Johannesburg.

That journey also involved his progression through the schools in the townships, the universities of the North and the Witwatersrand, St. Paul's, the Anglican theological college in Grahamstown, and his service in various parishes as an ordained priest, which became part of the process of his upbringing.

This was a journey which imposed on young Thabo Makgoba life experiences which helped to form the mind and character of the future Archbishop. These included the forced removals from Alexandra township, the 1976 student uprising and the mass struggles for liberation in which he was an active and visible participant, and exposure to the campaign of extreme repression with which the apartheid regime responded to these struggles.

It is in the context of this extensive exposure to and involvement in the lives of the African masses in our country that we must understand what Archbishop Makgoba wrote in this memoir, that:

"My own spirituality has been nurtured and developed by the experience of hearing of the pain, fear, anger, resistance, but above all of the faith and courage of my forebears."

Archbishop Makgoba gives an example of this pain and anger in the following account:

"My study and practice of psychology opened new horizons for me, giving me experience and skills which have served me well in my ministry since... So when after graduating I was asked to become the inaugural chairperson of a new initiative, the Tshwaranang Legal Advocacy Centre to End Violence Against Women, I readily agreed... (Ms) Mali Fakir, the dynamic head of a project called Women Against Woman Abuse (WAWA), which ran a shelter for women in Eldorado Park, south of Johannesburg... (said) we (the priests) should come out and see the problems at first hand. I did, and I was shocked... I couldn't believe that human beings could be so evil towards others as I listened to stories of men inflicting burns on women, kicking pregnant women, inserting objects into their orifices, stabbing them in their vaginas or cutting off their labia. I wept with the women and children as I heard of obscene phone calls, of incest, of a boy allowing a friend to rape his girlfriend and of children being raped in front of their parents. The work was depressing and it gave me a different attitude to life; I realised that man, if left to his own devices, could wipe out the whole of humanity."

As opposed to this harrowing experience, Archbishop Makgoba has written of an incident in which he was involved during the period of the Soweto student uprising, saying:

"One morning, after alighting from the bus from Noord Street, I was walking on my own to school when I heard the roar of an open-topped Hippo (vehicle) approaching behind me... Seeing armed troops standing up in the Hippo and looking towards me, I fled... I dashed into the yard of a local mechanic, Mr Shongwe, who was fixing a car. Terrified, I asked him to hide me. Leaving me under a car, he went out to the Hippo... 'Where's the terrorist?' a soldier shouted. By God's grace, Mr Shongwe stood up to them. In what I saw then and still see now, as an immense act of faith and courage, he told them off in language that I can't repeat here, accusing them of wanting to kill school children because they couldn't catch 'terrorists'... They responded by leaving. I lay there under the car weeping, feeling useless, scared, dirty with oil, not sure whether to go to school or back home.

I came out from under the car and asked Mr Shongwe. 'I think go to school,' he said. 'I'm scared,' I said. 'Then go home.' 'I'm scared.' 'Then I will take you to school,' he said, 'and explain to the teacher, and then you can go home and clean up because you are covered in oil.' As I write recalling that incident, the panic and tears surge up again... Through the prayers I offered while under the car... I think I subconsciously decided... that what that Hippo and those soldiers epitomised was not what I wanted to become in life."

Here, therefore, was an example of an act of resistance, of the faith and courage of his forebears, which served as yet another of the lessons which went into the making of he who was to become an eminent religious leader and Archbishop of Cape Town!

As indicated in the title of the book, the memoir contains a fascinating account of the intimate interaction between the Archbishop and his dear wife, Lungi, and Nelson Mandela and his dear wife, Graça Machel, especially during Madiba's latter years, and includes examples of prayers which are an important part of the story told by the Archbishop.

That account is also a moving tribute to Madiba whom Archbishop Makgoba celebrates as an exemplar of the faith and courage which should inspire all those who would be makers of history!

It also speaks to an important matter which is not often discussed in the continuing public discourse about Nelson Mandela - his spirituality. In this context the memoir recalls a moment during an interview with the scholar, Charles Villa-Vicencio, when Madiba quoted the poem by the English poet, Alfred Tennyson, and said:

Strong Son of God, immortal love,

Whom we, that have not seen thy face,

By faith, and faith alone, embrace,

Believing where we cannot prove...

The memoir does not indicate whether Madiba also recited the last verse of the poem, which says:

Forgive these wild and wandering cries,

Confusions of a wasted youth,

Forgive them where they fail in truth,

And in thy wisdom make me wise.

The memoir also reports a remarkable story that was told by Harry Wiggett, a priest who ministered to Nelson Mandela and others in Pollsmoor Prison. Minister Wiggett wrote:

"On (a) particular occasion, when I reached the Peace, Nelson gently stopped me and went over to the young warder on watch. 'Brand,' he asked, 'are you a Christian?' 'Yes,' the warder, Christo Brand, responded. 'Well then, you must take off your cap and join us round this table. You cannot sit apart. This is Holy Communion, and we must share and receive it together.' To my utter astonishment, Brand meekly removed his cap and, joining the circle, received Holy Communion."

Thus would all of this explain in practical terms the importance of the twinning of the phenomena of faith and courage and Archbishop Makgoba's attribution of both to Nelson Mandela.

The chapters in this memoir relate episodes and moments in the life of Thabo Makgoba, each of which confirm the truthfulness of the saying in the Book of Ecclesiastes that "To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven... "

They tell of the various seasons which have marked his life and helped to form his identity. They tell of the various times when he had to serve various purposes, with each moment in time posing the challenge to him to decide his purpose in life.

The preacher in the Book of Ecclesiastes says:

"Wherefore I perceive that there is nothing better, than that a man should rejoice in his own works, for that is his portion... "

The labour of love of reading this memoir means to be exposed to a very interesting life of a fellow South African about whom we surely have every reason to say that he himself did indeed "perceive that there is nothing better, than that a man should rejoice in his own works, for that is his portion... "

We too have every reason to rejoice in his works, even as we also join him to rejoice in the works of Nelson Mandela.

The book Faith & Courage: Praying with Mandela, includes an abridged version of this reflection by former President Mbeki. Published in Cape Town by Tafelberg, the book is available in South African bookshops from October 22. It can also be ordered within South Africa online from loot.co.za. A digital edition and print editions outside South Africa are forthcoming.