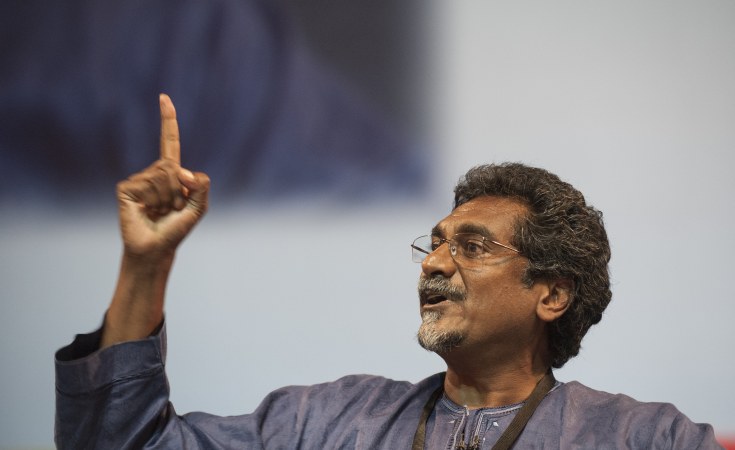

Currently a political and social activist, Jay Naidoo was a pioneering trade unionist who fought apartheid in South Africa and went on after liberation to serve as a minister in Nelson Mandela's cabinet. He is also a member of the board of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which this week published the latest edition of the Ibrahim Index of African Governance. He discussed this year's findings in an interview with AllAfrica's John Allen.

On improvements in the quality of governance across the continent:

Overall it remains positive, albeit off a very low base. But what is worrying for us in the foundation is that in recent years even countries that have made progress have slowed down, or we actually have seen reversals. So it is a wake-up call for us to show vigilance in holding leadership accountable – more so in South Africa than in many other countries.

Particular concerns over South Africa:

There's certainly been a decline in the accountability of public institutions and government that is worrying. That trend is continuing, as has been shown by the increasing evidence that much of our state - which is primarily responsible for the delivery of social and economic goods - has seen a decline.

It's quite predictable, given the political turmoil in our country, that we are continuing to fall behind in areas of accountability, certainly on the issues under the broad category of the rule of law. Although we have an exceedingly good judiciary and a number of checks and balances have been holding the executive to account, governance in state-owned institutions and the political sector has seen a decline.

On how useful the index is for tracking what's happening in a country:

The most important thing is that it works on data. If you look at the foundation, over 17 years we have consolidated data from 30 different independent institutions and increasingly we are also measuring, through institutions such as Afrobarometer, citizens' attitudes to delivery.

Data is the basis of executing the mandate that we have in delivering public economic, political and social goods. Statistics are in a poor state in Africa so the index contributes towards deepening the actual data required to measure the performance of our governments.

It is also important in helping business for investment purposes as they begin to use data to determine where they want to put their money.

From the side of citizens, it can become a very important tool as civil society begins to take up the issues that citizens feel most strongly about and put increased pressure on government to improve.

On trends in the "human development" category of the index:

If one looks at human development, what you see is steady progress, again albeit from a low base, in the areas of welfare, education and health. But what's happening now is that you are starting to see education registering the least amount of progress, and education is certainly the ladder out of poverty for the vast majority of African citizens. So I think it points to a weakness there.

On trends in the "sustainable economic opportunity" category:

Again we've seen progress over the last 10 years on economic growth. But it's been driven by commodity cycles, or by big infrastructure projects. It hasn't been able to deal with the huge problem of unemployment in Africa, and if you look at the data what you see is that the rural sector is declining at a rapid rate.

If you extrapolate from that, you see what is driving migration towards the cities. So the data begins to give you a more accurate scenario of what is coming down the pipeline. Even though it's not a predictive tool, it's an early warning system to say: pay attention to investing in rural areas because otherwise migration is going to increase, and migration leads to great, sprawling informal settlements in peri-urban areas.

Investment in rural areas would slow down that migration and create economic opportunities in the rural areas, allowing cities to cope better with the tremendous influx of people from rural areas. All of this is complicated of course by climate change, which is driving this migration.

If governments pay attention to this index, they are able to detect at an early stage some of the trends that are emerging out of it, and to take steps to try and remedy those changes that are negative and to implement game-changers that create a positive result. Data is the basis of governance and if we use it accurately we are able to allocate scarce resources in a more focused and targeted way.

On whether governments are using the index sufficiently:

Yes, if I think about it from the beginning, when they didn't even want to hear about the index and weren't prepared even to consult on it, now a number of heads of state of important countries wait for the index to come out and then ask themselves, why have I fallen, or celebrate when they do right.

So I think governments, not all governments but certainly a number, are beginning to interact with it and are beginning to see the index as a very useful tool for improving governance and performance in the delivery of goods to citizens.

On trends in the category "participation and human rights":

It seems at the level of the formal institutions of participation, people are feeling that there are more free and fair democratic elections. But that doesn't automatically translate into those governments that are elected being accountable.

Again, in the case of South Africa, where we have a government with an overwhelming majority through elections - the African National Congress - it's a government that is increasingly unaccountable, whether to that same organisation or to us as citizens. So we have what I would call an element of electoral authoritarianism, where a government is democratically elected but believes that it does not have to consult the people for the period for which it has been elected, which in our case is five years.

That doesn't mean that there is participation: it means that elections are free and fair but what happens after that is a collapse of government, when the government believes that they have some divine right to rule us.

What is very clear is that civic and political space, particularly for citizens' action, for civil society, is falling behind. Countries believe that because there is political participation therefore it means there is absolute freedom. But if you take Kenya, for example, where the judiciary has just ruled that Uhuru Kenyatta's election is accepted, it doesn't mean that civil and political space is free for citizens to raise their issues. Increasingly you see attempts to impose controls - financial controls on civil society, on international civil society, on human rights groups.

Even in South Africa we are beginning to see this, an attempt to demonise independent journalism, to demonise civil society that is challenging government on a range of different fronts, whether that is on education or the health crisis.

For me, the index points to a very focused closing of that civic and political space for citizens to raise their legitimate grievances and hold their governments accountable.

On whether civil society uses the index effectively to pursue their aims:

I don't think at the moment it is effectively used as a tool because the index is quite a technical instrument. There is a broad conversation taking place between the foundation and civil society in Africa, with a recent grassroots movement called Africans Rising, chaired by Kumi Naidoo, the former head of Greenpeace International.

That movement is in very serious conversation with the Mo Ibrahim Foundation in looking at how the index can become a more useful tool for civil society in their campaigning for the rights of citizens. The foundation considers itself a non-governmental organisation, it's not a government organisation, it's not a business organisation, it's part of civil society, so we use a number of mechanisms to try and co-ordinate with civil society around the improvement of governance and indicators that we are measuring in the index.

I'm looking forward to a deeper partnership between independent civil society groups and the foundation around the area of improving good governance and excellent leadership in Africa.

On whether it is realistic to try to award the foundation's Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership – given to outgoing heads of government and state for exceptional leadership – every year:

The idea was that we were measuring governance across 54 countries, so there's always a pool of heads of state stepping down who have abided by their constitutions. But we are continuing to have a very deep conversation about the impact of the award.

For the moment we've kept it as an important incentive to those who have not yet abided by their constitution, but who have proved excellent in leadership, who have taken extraordinary action to promote social cohesion in their societies and who have been outstanding models of integrity.

I think the fact that the prize is not issued every year is a very powerful signal to those that are executive heads of our states that it does not mean that if you just comply with the constitution, you get the award. I think the fact that we haven't issued it for 2016 is a very important signal that we are concerned and disturbed at the lack of candidates who are worthy of this award. But the fact that we've issued it four times in the last 10 years highlights that there are heads of state who have been worthy and who are role models.

If this award were given in Europe in the last 10 years, who would have qualified for it? In my mind definitely not Berlusconi in Italy, nor Sarkozy in France nor Tony Blair in the UK. Potentially, one person who would deserve an award equivalent to this would be Angela Merkel for her courageous stand on the issue of immigration, taking refugees into Germany even though she knew it was politically dangerous to do that. It showed courage.

So for me the award is an important indicator, an encouragement to leadership but it's not the silver bullet. The index is a much deeper and more profound instrument that can be used by citizens, by civil society, by business and by government to improve good governance and leadership in Africa.

More coverage of the report