Africa may have driven out colonial occupiers generations ago, but some of the laws they passed remain stubbornly in place. For instance, in at least eight African countries like Malawi, Nigeria, and Kenya, attempting to commit suicide is against the law.

The problem is, people do not seem to be deterred. African countries average 10 male suicides per 100,000 per year. Taking Malawi as an example, the country has actually witnessed a surge in attempts in the last two years. Currently one person dies here this way every other day. And rather than preventing people from taking their own lives, this law against suicide may actually encourage it. That is because criminalizing suicide keeps desperate people from reaching for the help they need. May is Mental Health Awareness Month, a good time to examine all the reasons to rid ourselves of these dangerous laws.

As one of the few clinical psychologists in Malawi, I have witnessed the penal code's chilling effect. I once saw a young man for psychotherapy who denied he had tried to hang himself. His family suggested that the rope had merely gotten tangled around his neck by accident. Their focus was on avoiding a potential criminal case and having to foot the exorbitant hospital bill since medical aid does not cover suicide attempts. These fears made covering up the suicide attempt more important than addressing its underlying causes.

Keep up with the latest headlines on WhatsApp | LinkedIn

And these worries are well founded. For hospitals, reporting a suicide attempt to law enforcement is standard procedure. Last year, when one of my employees took an overdose, the private hospital that treated her told her to turn herself in to the police. I intervened and was able to spare her from possibly facing arrest, prosecution, a jail term, and a criminal record. But she too will be harmed by our law. Will she want to go back to that hospital or elsewhere to seek counseling and treatment? I doubt it. Admitting what happened would mean confessing to a crime. So, the law will likely deny her the help she needs with the very problems that made her suicidal in the first place.

Suicide is a tragedy for families and communities and has long-lasting effects on the people left behind. Apart from the pain, many relatives are left with guilt and regret, and in Malawi, with the additional burden of lying about what happened.

By forcing people to cover up the truth of their pain, this law, Criminal Code Chapter 21, Section 229 of the Malawi Penal Code does incalculable harm. So do similar laws in the other seven African nations. The threat of punishment keeps those with mental health problems in the shadows. This is one reason why 90% of those in Africa who need mental health treatment do not get it.

And yet definitive academic studies show that suicide attempts are often cries for help, and that counseling can effectively address the reasons why people attempt suicide, such as depression, conflicts and breakups. Numerous other systematic reviews demonstrate that counseling a person with depression works.

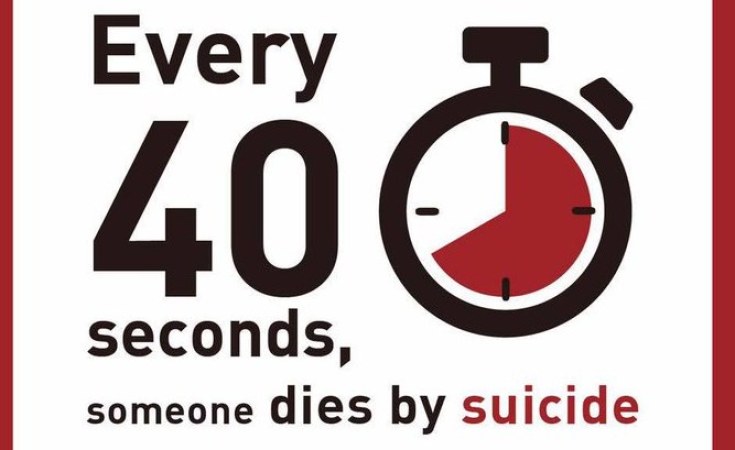

Worldwide 20 times more people attempt suicide than actually commit it, according to the WHO, which has also concluded that most suicides are preventable. The e-Journal "Thought Catalogue" points out: "People who are suicidal don't want to die, they just want the pain to stop" and they can get better.

My clinical psychology experience, counseling those who have attempted suicide, bears this out. It leads to patients getting better and addressing their mental health issues. Often, they later express regret for what they did and they go on to live happy and productive lives. Such people to not need to be branded criminals. They need compassionate assistance, and elsewhere that is what they would get. Laws that treat suicide as a criminal, rather than a mental health problem, mean mental health problems get swept under the carpet.

The time has come for African mental health professionals to unite and speak out against these laws. Together, they and family members affected by suicide should pressure legislators to repeal this harmful legacy of British colonial rule. Britain abolished its anti-suicide law back in 1961. It can be done, Singapore, a former British colony, decriminalized suicide on the first day of this year. It stands out as an example and beacon of hope for health care workers who seek to bring change.

It makes no sense to continue to marginalize and stigmatize people with mental health issues. Why take people who are suffering and add to their pain? Why turn people who are desperate and vulnerable into criminals, rather than helping to heal them and possibly save their lives? Malawi, Kenya, Nigeria and other countries with anti-suicide laws should repeal them.

Chiwoza Bandawe is a clinical psychologist with the University of Malawi, College of Medicine. He has several publications in international journals and has published three mental health education books.