Cape Town — When the Democratic Republic of Congo's largest-ever outbreak of Ebola first emerged in the north-east of the country in 2018, it appeared that it would remain small and relatively isolated.

A government that had successfully contained nine previous outbreaks since Ebola was first identified in the country in 1976, first looked set to beat back the one which erupted in North Kivu province.

Having just successfully declared an end to an outbreak in the north-western Équateur province after only three months, the government launched – with international help – what a World Health Organization (WHO) study later called "the fastest, best-equipped and best-funded" fightback in the history of Ebola responses.

But it took nearly two years to contain the North Kivu outbreak, a period during which 3,481 people were infected, of whom 2,299 died. The 2018-2020 outbreak was the world's second-largest after the West Africa outbreak of 2014 to 2016.

What went wrong?

A study just published by the UK-based Overseas Development Institute and produced with input by Research Initiatives for Social Development (RISD-DRC), based in the DR Congo, provides some answers, and some lessons for the future.

The study says the initial response from the DRC government and the WHO "came tantalizingly close to containing the virus during the outbreak's early weeks".

But its eventual containment came more slowly than first expected, and only after "significant, and belated, corrections to the response's leadership, the coordination model, and the response strategy".

After carrying out more than 120 interviews and examining other studies, a 62-page institute report cites as among the reasons it took longer than expected to end the outbreak:

- The people of North Kivu were unfamiliar with Ebola, previous episodes having occurred far away;

- Local health structures were weak, with doctors and nurses lacking basic knowledge of Ebola and clinics lacking equipment, including personal protective equipment;

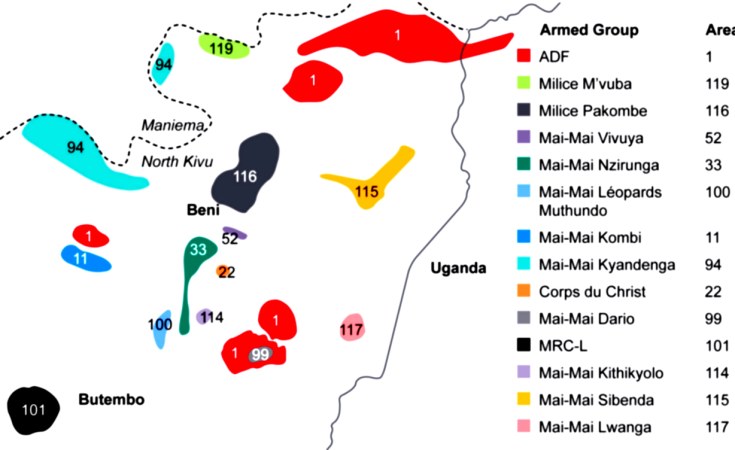

- The region has gone through decades of conflict – the study named 14 armed groups scattered through North Kivu; and

- Distrust of the government, other outside agencies and even aid workers and researchers, among local people and medical staff.

"For decades the Grand-Nord (area of North Kivu) has been under attack by foreign and local armed groups… and by a national military presence that is perceived as a foreign, occupying force," the report says. "The population is often caught in violence between irregular armed groups and government forces engaged in counter-insurgency."

The DR Congo's government and the WHO are criticised for first using a response plan developed for a different environment:

"At the heart of the poor context analysis was a lack of sensitivity to the depth of hostility in the Grand-Nord of North Kivu for the central government and its representatives, with whom WHO worked closely."

The report adds: "The population's scepticism for authority and distrust of officialdom fairly quickly manifested itself in resistance to the top-down, fear-based public health messaging employed by Ebola response teams at the source of the outbreak."

The institute's study reveals that money was also at the root of community suspicion and resentment: not too little of it, but too much of it.

The Armed Forces of the DRC (FARDC) and the Congolese National Police (PNC) received "generous salary top-ups paid by the international response budget," the report says.

"The introduction of a billion-dollar response into an area characterised by a complex humanitarian crisis where basic needs are perennially underfunded helped fuel real and perceived instances of waste, corruption and fraud, commonly referred to as 'Ebola business'." The report cites other studies as finding that this contributed to sexual exploitation and abuse.

"'Ebola business' was a perception among affected communities that resources marshalled for the response inordinately benefitted authority figures and response providers rather than victims, survivors and their communities," the report adds.

"Inflated payments for armed escorts, medical responders and community volunteers were cited by many as key components of the Ebola economy and served as a perverse incentive to continue the outbreak rather than end it.

"That the outbreak was deliberately stoked and/or the response debilitated in order to prolong 'Ebola business' was emphatically asserted in interviews, including with senior UN security and political officials."

In addition to addressing these problems, the report recommends that in future a more inclusive and coordinated response is needed to fight Ebola, especially in areas of conflict or humanitarian need.

An institute news release quoted Nicholas Crawford, the lead author of the report, as concluding: "In future outbreaks in complex and conflict settings, there's no room for a 'go-it-alone' approach."