The DRC, its neighbours, the AU and international community have failed to translate military victory into political success.

On 23 January, the Rwandan Air Force fired at a Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) military jet in Goma, claiming it had violated Rwandan airspace. This was the tipping point in rising tensions between the two countries, which are now on a war footing.

Ten years after its defeat by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Force Intervention Brigade, the M23 rebel movement is resurfacing in eastern DRC. This shows the inability of the DRC, its neighbouring countries, the United Nations (UN) Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the African Union (AU) to translate military victory into political success.

The East African Community's Nairobi Process aims to link political consultations with military action in eastern DRC. However the latter, particularly the deployment of the regional force in North and South Kivu provinces, remains more advanced than the political process, which isn't helping to demobilise armed groups.

The recent proliferation of peace initiatives in the Great Lakes region hasn't made combining political and military solutions easier. This is partly because the M23's defeat in 2013 was not accompanied by efforts to deal with the conflict's root causes. Instead, the group withdrew from Goma and cantoned its troops in Rwanda and Uganda after being expelled by regional forces and fragmented by internal divisions.

The proliferation of peace initiatives hasn't made combining political and military solutions easier

Political dynamics in the DRC and international developments added to the problem. After repeated waves of disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration, the DRC government and international partners grew reluctant to integrate M23 combatants into the national army. When the armed group was defeated, DRC politics became dominated by other matters, and the international community adopted a reactive approach to Great Lakes problems.

The troubled region is on the agenda of the Peace and Security Council's (PSC) heads of state meeting on the margins of this month's AU summit. This is mostly a reaction to the fact that the M23 now occupies a significant part of North Kivu.

The regional dimension of the M23 issue has been exaggerated at the expense of local and national dynamics, which need more political attention. This imbalance results from evidence presented by the UN Group of Experts on the DRC in their December 2022 report, alleging support by Rwanda and Uganda for the M23 rebels.

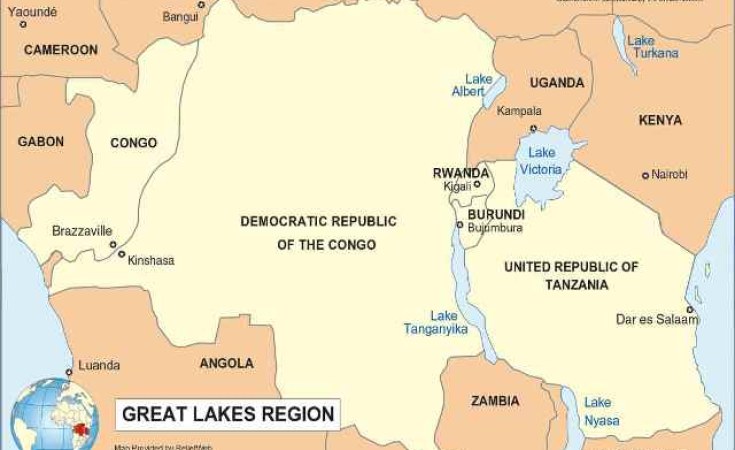

Great Lakes region of Africa

Tanya Harris/ISS

(click on the map for the full-size image)

Also, if countries are supporting rebels, that suggests regional security instruments aren't creating enough space for dialogue, which would prevent states from using proxy armed groups. Differences in threat perceptions between Kigali and Kinshasa create security dilemmas in the eastern DRC.

The UN Security Council kept surprisingly silent in the face of allegations in the Group of Experts' report. This will likely encourage several regional actors to use direct or indirect violence to settle disputes.

Despite several regional initiatives, the 2013 Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework for the DRC and the Region remains central to resolving the crisis. But the PSC has repeatedly called for a review of the framework, as requested by the DRC. Is this the best way to build consensus in a highly polarised region? If agreement is reached on a review, three issues must be considered: balancing national and regional commitments, managing bilateral alliances, and the crucial role of guarantors. Some Congolese decision makers criticise the fact that the agreement identifies national commitments for the DRC only. Observers say resolving the problem of foreign armed groups operating in eastern DRC also requires political reforms in the countries involved. Such reforms are unlikely under the current regimes in Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda, but the next PSC summit should consider this dimension.

The trust deficit between the DRC and some of its neighbours is at the heart of the current crisis. Some observers note that the trigger for escalating tensions between Rwanda and the DRC was the latter's rapprochement with Uganda and Burundi to fight their respective rebel enemies inside the DRC.

The regional dimension of the M23 issue has been exaggerated at the expense of local and national dynamics

The DRC's attempt to create a regional military command against armed groups in 2021 was stymied by mistrust between Rwanda on the one hand, and Burundi and Uganda on the other. The region's political culture is dominated by short-term alliances that conflict with Tshisekedi's vision of cooperative security.

Finally, security in the Great Lakes, as outlined by the 2013 peace framework, requires individual states' commitment and the strong involvement of guarantors. Some observers suggest the East African Community be a guarantor along with the UN, AU, International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) and SADC. But guarantors should only be added if their role in rigorously ensuring that states implement their commitments is clear.

The competition between SADC, the East African Community and the ICGLR over peace initiatives - and through them Kenya, South Africa and Angola - isn't conducive to productive joint monitoring of member states' commitments. Also, divisions in the UN Security Council and the AU's silence on recurrent violations of the 2013 peace framework raise questions about their willingness to ensure signatory states respect their obligations.

Stability in the Great Lakes depends on a rigorous and shared diagnosis of threats and existing peace efforts. Countries in the region must also renew their agreement on resolving the challenges of insecurity and poverty. The AU should demonstrate more leadership and involvement in one of Africa's most unstable regions.

Paul-Simon Handy, Regional Director for East Africa and Representative to the African Union, ISS Addis Ababa