Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo — Kisangani, one of DRC's biggest cities, is now home to hundreds of Revivalist churches, the product of a pandemic boom that has come with serious side effects.

When Blandine Masuaku joined Jésus-Christ la Solution Revivalist Church, she was in the market for a place of worship that could heal her from a chronic disease. One day, while sitting at home reading the Bible, the mother of two saw an advertisement for a church on TV. It swayed her. This was the church for her.

"The reason I'm here now is because I want to heal," Masuaku says.

Even before joining Jésus-Christ la Solution, Masuaku was spoiled for choice. There were churches everywhere in Kabondo, a commune in Tshopo province in the city of Kisangani. Already, she had been a member of at least four other churches.

Revivalist Christian churches -- churches that departed from Catholic and Protestant teachings during the Revivalist movement -- have proliferated at a high rate, particularly during the pandemic. Some locals accuse them of exploiting their followers, causing noise pollution and driving up the cost of land, and they are calling on the government to regulate them.

A 2019 study published in Anuac, an international peer-reviewed journal, links the popularity of Revivalist churches in DRC and the lack of social services in the country: For example, while health care remains expensive and inaccessible to many, revivalist churches treat diseases and illnesses as a "spiritual problem," according to the study.

Recent data is not available, but in 2010, 32% of households in DRC identified as Catholic, 31% as Protestant, 14% as Revivalist Christians and 3% as Kimbanguist, according to a national survey conducted by the United Nations Children's Fund and the country's national statistics office.

While Revivalist churches are not the majority, Jean Louis Alaso, Kisangani's mayor, says that there are at least three of these churches on every street in Kisangani. About 450 churches opened between 2020 and 2022, a number that doesn't account for unregistered ones, he adds.

Alaso sees a connection between the coronavirus pandemic and the recent increase in churches. Locals fell prey to pastors who convinced them that if they joined their church and prayed, they would not contract the coronavirus, he says, which also pushed new churches to open. It didn't help that state services were minimal during this period, which Alaso says made regulation difficult.

Now, locals are noticing the consequences. The cost of land and rent has increased as pastors buy land in the city or rent commercial and residential buildings at a higher price. "Before 2018, plots of land used to be sold at $1,000, whereas today, pastors pay at least $5,000 to purchase them," Alaso says.

Patrick Kadosa, who sells land in Kisangani, agrees. He makes more selling to church leaders. "We used to sell our plots at $500. Today, pastors will pay between $5,000 and $6,000," he says.

Boni Lipasa, a state official, has been saving for a few years to buy land for his family. He tried to buy but was surprised by the significant increase in price. "In Kisangani, we all knew that the most expensive land is sold [at] $2,000, but today, the owner tells me to pay [him] $5,000," he says.

Noise pollution is another issue. Cathy Lomeya, a mother of four who lives 10 meters (33 feet) from a church, says it has become a daily disturbance. Sometimes, her children cannot read or do homework because of the noise. She sees a need for authorities to regulate churches in the city.

"These churches [operate] as if nothing is forbidden," she says.

According to a 2001 law regulating nonprofit organizations, places of worship should not disturb neighbors. The law also outlines requirements for the legal representatives and founders of religious institutions. Both must be of sound mind and have good moral standing. The legal representative of a religious institution should also have theological training from an approved institution and have no record of any custodial sentence longer than five years, among other requirements.

But Kisangani's Revivalist churches don't always meet these conditions. Alaso says that in 2022, the city authority closed 35 churches. However, he adds, they face challenges as more churches keep sprouting.

"We, the local authorities, are at our wits' end," he says.

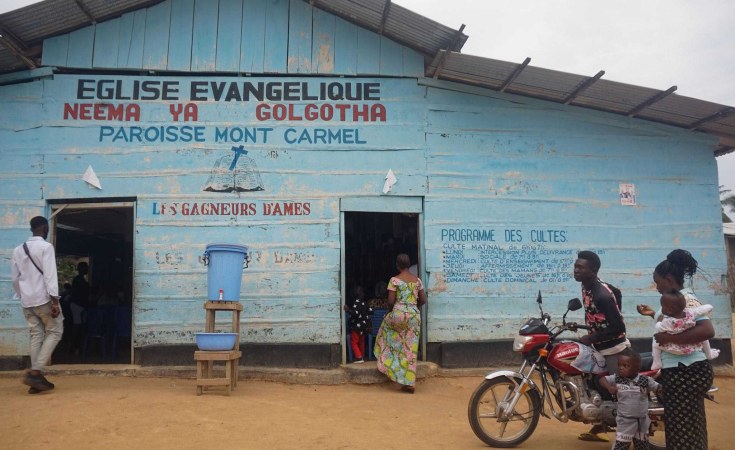

Elie Kawaya, a pastor, holds a degree in theology and has been operating the Neema Ya Golgotha Evangelist Church in Kisangani for several years now.

Kawaya says he meets most of the legal requirements. "As a Congolese man who loves his country, it is my job to ensure that I run my church in accordance with the law," he says. He concedes that some pastors are out to exploit. "A church should not be a place of business where pastors preach for money. Instead, it should be a place where people can be shown the path to the Lord in order to be saved."

Masuaku, who says that her condition has improved since she joined Jésus-Christ la Solution Revivalist Church, finds the law somewhat problematic. "I pick which church I want to join, and I don't let others decide for me," Masuaku says. She sees no sense in the requirement that a pastor must have a degree in theology. "Courage and the gift of God," she says, "are all a pastor needs."

Françoise Mbuyi Mutombo is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Democratic Republic of Congo.

TRANSLATION NOTE

Emeline Berg, GPJ, translated this story from French.