The Department of Health is not planning to buy the new COVID-19 bivalent booster vaccines, specifically tailored to target Omicron variants, anytime soon.

Instead, people in South Africa will continue to be offered the standard booster Pfizer-BioNtech and Johnson and Johnson (J&J) vaccine doses. The department and vaccine experts advise those individuals who are over the age of 60 years, especially those with underlying conditions who have not had their fourth dose, to do so as soon as possible.

Health department spokesperson Foster Mohale says that the Vaccine Ministerial Advisory Committee (VMAC) has decided that the bivalent or “updated” vaccines, approved for use in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration, are on the “to-do list” but are not a top priority because they are not registered for use in South Africa and there is no “compelling evidence of their superiority over standard vaccines”.

“Currently, South Africa is not ordering any vaccines because we have enough stock of perfectly good vaccine,” Mohale says.

The department is sitting on a huge stockpile of 29.7 million COVID-19 shots, having ordered enough doses for the country’s adult population. However, dwindling cases and hospital admissions for COVID-19 have seen demand for the shots sharply drop. According to the department, by 6 February 22.5 million people in the country, had received at least one dose.

On 30 January, another round of COVID-19 booster doses of either the Pfizer or J&J vaccine was made available. South Africans aged 50 years and older were invited to get a fifth dose and those aged 18 to 49 years a fourth dose.

Prior to opening for more boosters, health minister Dr Joe Phaahla said government had been inundated with requests from fully vaccinated individuals, especially those most at risk, for booster doses to protect them against current and evolving COVID variants. By 6 February, a total of 19 102 booster doses have been administered in the seven days prior. The total number of boosters since the start of the booster campaign by then stood at 4.2 million.

Some people have contacted Spotlight, wanting to know when people in South Africa will have access to the bivalent vaccines. Some South Africans have taken advantage of getting the updated vaccine while visiting the United States, believing it to be a better vaccine. The US Centers for Disease Control recommends that all age groups, with a few exceptions, get a single bivalent boost after having received the primary series (initial doses) of the vaccine.

Private sector procurement

Mohale says private companies and healthcare providers wishing to buy COVID-19 vaccines, including bivalent vaccines, will have to ensure that they are registered with the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA). “Unfortunately, the doses will not be a part of the national programme and will not be recorded on the Electronic Vaccination Data System,” he says.

SAHPRA spokesperson Yuven Gounden confirmed that no private manufacturer or company had registered a bivalent booster vaccine with the regulatory body.

Monovalent vs Bivalent

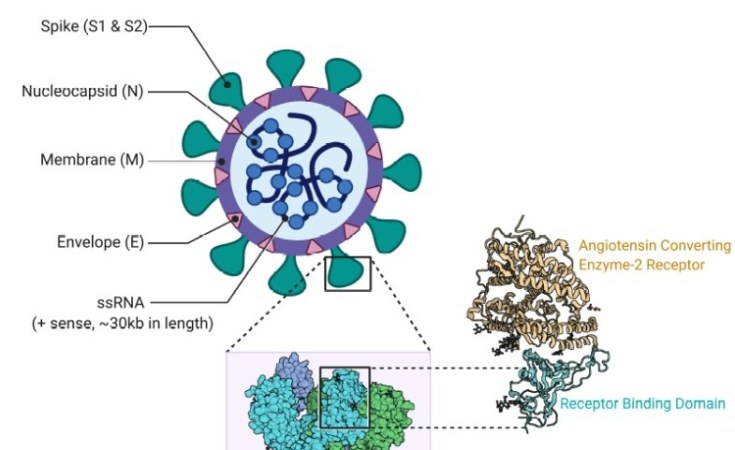

In 2020, all the COVID-19 vaccines were designed to prevent disease caused by the original Wuhan-1 strain of SARS-CoV-2, often referred to as the ancestral strain. These are called monovalent (one virus strain) vaccines. Since then, the virus has rapidly evolved, replacing the original virus with a number of variants, which have been able to evade the body’s immune system and lower the efficacy of these vaccines. Omicron, with its subvariants, is the most dominant and transmissible variant, resulting in breakthrough infections and reinfections.

The benefits of the mRNA technology used in the vaccines made by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna is that vaccine formulations can be tweaked to match a quickly changing virus. To provide better protection against the Omicron variant, Moderna and Pfizer-BioNtech have updated their mRNA vaccines to accommodate two virus strains (bivalent). Half of the vaccine targets the original strain, and the other half targets the BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron subvariant lineages, including the XBB1.5 which has a mutation that is believed to help the virus bind to cells, making it more transmissible.

Are bivalent vaccines more efficacious?

Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences and Professor of Vaccinology at the University of the Witwatersrand, Shabir Madhi, agrees with the VMAC that the scientific data on bivalent boosters is not compelling enough. This is especially so for protection against severe disease and death, which he says is more durable – there is less waning immunity – than in trying to protect against mild disease or against infection.

The World Health Organization’s position is the same with its Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation advising that it’s important for people to get boosted, especially high-risk individuals, but that can be with either the monovalent or bivalent vaccine, Mahdi says.

Observational studies comparing monovalent to bivalent boosters show that while the latter has some additional (although probably transient) benefit in preventing infection due to Omicron variants, almost all studies show no additional benefit of the bivalent compared to monovalent boosters against severe disease.

Madhi explains that protection against severe disease is due to T-cell immunity, which has been relatively spared in spite of the mutations that have occurred with Omicron. “Protection against severe disease is going to be similar because the bivalent is not introducing a different repertoire of T-cell responses against Omicron.”

Protection against mild-to-moderate disease

Madhi explains while the data shows that the bivalent booster induces more neutralising antibodies against the Omicron variant, including XBB1.5, immunity wanes. “So even though the bivalent vaccine offers some benefit in protecting against mild-to-moderate COVID, that benefit is somewhat transient, in that it probably lasts between 16 and 20 weeks,” he says.

“You are pretty much back to square one and probably in a similar sort of ballpark in terms of protection compared to the monovalent vaccine. But, when it comes to severe disease, there isn’t any evidence to indicate that the bivalent vaccine would be superior to a boost with the monovalent vaccine.”

This, he says, is especially important in the South African context where nearly three-quarters of the population has been infected with the Omicron variant, “which itself would induce an immune response that is somewhat slanted in protecting against future variants of Omicron”.

A recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found the effectiveness of the original (monovalent) booster against severe COVID-19 was about 25%. The effectiveness of the bivalent booster was 62%. Overall, the bivalent shots were 37 percentage points more effective at preventing severe Covid-19. Effectiveness was similar between the two different brands (Moderna and Pfizer), and whether or not people had received one or more boosters previously. Protection from both shots peaked at about 4 weeks after which immunity waned.

While there was generally positive reaction to the results, Madhi says there were problems with the study design regarding the timing of the booster shots.

When to get a booster?

Madhi says to truly benefit from the boost, especially in protecting against mild-to-moderate COVID-19 disease, you need to time the boost to coincide with an upswing in the number of cases and with the next wave. “So if you boost now with the monovalent vaccine and the next wave occurs only 20 weeks from now, you’re not going to benefit much at all in being protected against mild-to-moderate disease, because by then the antibody would have waned.

While Madhi would not insist on the bivalent vaccines, he says the reason the department is not buying the vaccine “likely indicates they’ve got a massive surplus of monovalent vaccine that’s going to expire and it’s (the bivalent boost) going to be an additional cost. So it’s going to be more money pretty much flushed down the drain, especially when people are not interested. Essentially, the number of individuals getting a fourth dose of vaccine is nominal.”

Madhi says while the department argues that there are no prohibitions on the private sector from importing vaccines, the regulatory framework needs to change. Especially, he says, liability cover in the event that a person who has received a private sector-procured vaccine develops a vaccine adverse event.

Mohale confirmed that vaccines procured by and administered in the private sector are not covered by the government’s COVID-19 Vaccine Injury No-fault Compensation Scheme.

Madhi says, “Once the scheme is extended to the private sector, companies will become more engaged.”

He points out that the US CDC’s decision to recommend the bivalent vaccine “to all and sundry” is more of an anomaly rather than the norm. The focus of the UK and the WHO is primarily on boosting high-risk individuals.

“It’s difficult to understand what [the] United States is trying to achieve by just asking everyone to be boosted with the bivalent vaccine,” he says.

“Most importantly, South Africans over the age of 60 years, especially those with underlying health conditions who have not had their fourth dose, should get it as soon as possible. The evidence is clear that a fourth and fifth dose does increase protection in this age group,” Mahdi says.