Addis Abeba — In the aftermath of the Tigray war, Ethiopia has unveiled a draft of its comprehensive Transitional Justice Policy, marking a decisive moment in the country's effort to come to terms with its turbulent past. However, the document, while embodying substantial potential, raises considerable questions about the feasibility of its implementation, revealing a nation caught in a vortex of post-conflict justice and accountability issues.

The transitional justice policy options document which was announced by the Ministry of Justice was open for stakeholders consultation as of February 2023, and was hailed by the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) as an essential step in the implementation of the Agreement for Lasting Peace and Cessation of Hostilities signed by the Government of Ethiopia and the Tigray Peoples' Liberation Front on 02 November, last year.

The draft document, named Ethiopia Policy Options for Transitional Justice has a broad remit, intending to address crimes committed since 1991 and to facilitate reconciliation and accountability. While the text is highly anticipated, it's the context and provisions for implementation that have raised eyebrows among experts.

Addis Standard has recently spoken with experts in the field of human rights and transitional justice, each of whom expressed apprehension about the practical hurdles inherent in the current draft and concerns regarding the broader circumstances that underpin its creation.

Sovereignty Vs Inclusivity

Yared Hailemariam, the Director of the Ethiopian Human Rights Defenders Center (EHRDC), noted the draft's lack of comparative experience, which is vital for tackling the intricate mesh of Ethiopia's political crisis and human rights abuses.

More notably, Yared argued that the document's emphasis on national sovereignty has led to the exclusion of international actors and processes, which are crucial to the transitional justice process. "International actors who have accumulated experience in facilitating transitional justice around the world are needed for this transitional justice process to be effective", said Yared.

This position was echoed by Merga Fekadu, a Human Rights Lawyer and lecturer at Wolkite University, who said the draft document uses the concept of sovereignty in order to limit the role of non-state actors, and stressed that the African Union's role should not be sidelined, given its significant contributions to the peaceful resolution of the Tigray war.

He also underscores the importance of civil society organizations, which he believes could play an instrumental role in facilitating public dialogue, fostering reconciliation, and promoting accountability at the grassroots level.

Furthering the arguments of Yared and Merga, Abadir Ibrahim, Director of the Human Rights Program (HRP) at Harvard University School of Law said, the draft policy's "adoption of a hyper-nationalist position that emphasizes national sovereignty and national pride is used to justify the non-negotiable position on excluding international actors and processes".

"The fact that this is made non-negotiable is explained by a context in which the Ethiopian government has been aggressively trying to prevent, thwart or hamper any independent investigation including that of the United Nations" Abadir said.

He offered further insight, focusing on the context in which the document was conceived, namely its framing by Ethiopia's Ministry of Justice. This, he contends, is problematic given the Ministry's potential implication in past abuses, adding layers of questions about credibility and independence.

He added that "it is also not clear, at least not based on the document or based on publicly available information, whether this whole process could have been conducted in a way that is seen as acceptable by political actors and stakeholders that may be relevant to both a future political settlement and to transitional justice - even if under the Ministry of Justice".

Timing

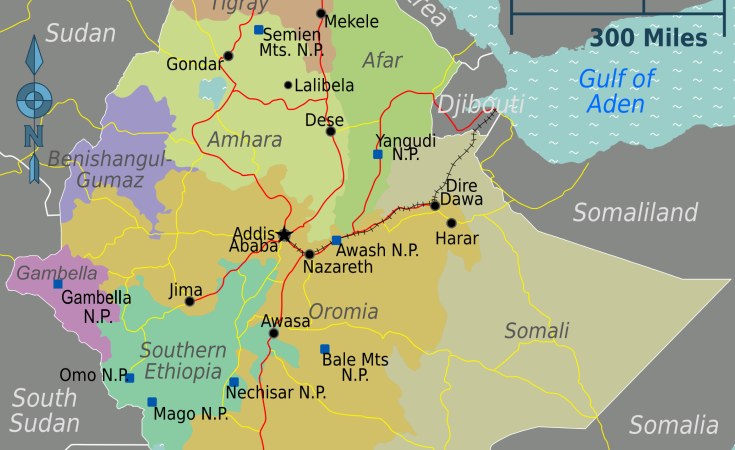

He further argues that an overall political transition should precede transitional justice, something that Ethiopia, currently still mired in civil wars in the Oromia and Amhara regional states, may not be ready for. Abadir also commented on the problem of ongoing armed conflict in the country, noting that while transitional justice is not inherently incompatible with conflict, the nature of Ethiopia's situation complicates matters.

"Given the fact that the war, or wars, are an extension of failure to find political settlement, if Ethiopia does not attain political settlement, wars are likely to continue and this makes transitional justice in a way superfluous since transitional justice is meant to help the nation which just transitioned from authoritarianism to democracy or from war to peace".

"If the country's political actors are still talking on the battlefield the whole notion of transitional justice may have to wait until they decide to make peace - whether that peace will lead to another opportunity at democratization is another story" Abadir stressed.

In consensus with Abadir, Merga asserts that Ethiopia's current socio-political climate may not be conducive for the execution of transitional justice. He succinctly phrases, "Political transition is the raison d'etre for transitional justice," thereby indicating that the country's current political dynamics, characterized by conflicts and entrenched political divisions, may impede the implementation of transitional justice.

On 13 March, Addis Standard reported that several leaders of opposition political parties who were invited to take part in the nationwide consultations on transitional justice policy options have walked out of the meeting urging the government to give priority for peace and national political dialogue.

Scope

Adding another layer to this critique, Merga emphasizes that the process of transitional justice must be comprehensive and shouldn't be confined to post-1991, since there are historical injustices and grievances that are affecting relations of ethnic groups and causing political polarization and violence.

Another glaring gap within the draft document is its failure to provide a comprehensive account of casualties across Tigray, Amhara, Oromia, and other regional states - a deficiency noted by both Yared and Merga.

"The extent of casualties, human rights violations, the impact of the war on women and children, identifying the perpetrators and the victims, etc. have not been properly addressed in the drafted document" Merga noted.

Moreover, the experts question the technical capabilities and impartiality of public institutions, such as the military, police, and judicial system, in the enactment of transitional justice. These institutions, often instrumentalized as tools of repression and human rights abuses during conflict, the effectiveness of transitional justice needs rigorous reforms to these institutions, argues Yared.

"I don't think the police, military, judiciary, and especially the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission are ready to deal with transitional justice for two reasons," Abdir explained, "first, the scale of violence is so tremendous that they are simply not going to have the capacity, skill, or even personnel baseline to deal with such a titanic project. Second, because of the authoritarian control that still exists over these institutions".

Notwithstanding these criticisms, the development of the transitional justice draft document is a significant step, the experts noted. For Yared, the drafted document is "workable," but only if there's genuine political will to see it through.

In a similar vein, Abadir lauded the document's technical aspects, its successful incorporation of crucial elements and viable alternatives pertaining to transitional justice, but raised concern whether the government is interested in conducting an honest process of transitional justice and is willing to subject itself to investigations and possible processes of justice. AS