The long-awaited Global Goal on Adaptation puts Africa at the periphery of an agenda that's central to its development.

As the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events has risen sharply over the past decade, there has been growing recognition that taking actions to adapt to the impacts of climate change must be one of the core pillars of the global response to the crisis.

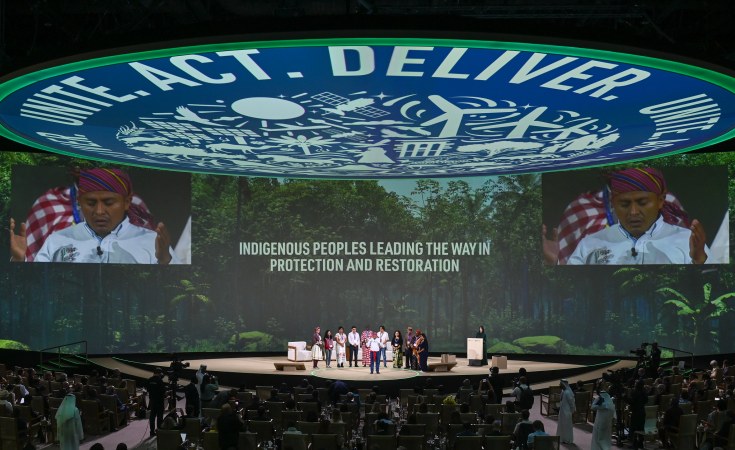

At the COP28 climate talks that concluded in Dubai last week, adaptation was high on the agenda and one of the key outcomes was the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). The concept of GGA was first proposed by the African Group of Negotiators in 2013. It was established, though not operationalised nor defined, as part of the Paris Agreement in 2015. At COP26 in 2021, a two-year work programme was launched to define the GGA. The hope has been that the goal can become a tool for enhancing adaptation actions and strengthening global governance of adaptation more generally.

In the UAE, this process finally concluded.

On certain technical aspects, there was remarkably good progress, even if it was long overdue. For example, parties affirmed the link between adaptation and the goal of limiting global heating to 1.5C, thereby shifting adaptation closer to the core objective of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC). There was also agreement of targets by 2030 that pursue the collective well-being of all people, the protection of livelihoods and economies, and the preservation and regeneration of nature. And there was a deal on targets in relation to the five dimensions of the "iterative adaptation cycle", which are impact, vulnerability and risk assessment; planning; implementation; and monitoring, evaluation and learning.

There was similarly positive progress on aspects to do with the process of the GGA. The two-year Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work programme was concluded; a framework for adaptation with a clear purpose and objectives was adopted; there was agreement to continue discussions from June 2024 to November 2025; and parties launched a new two-year work programme to decide on indicators for measuring progress. Agreeing on the process to continue structured negotiations is particularly important as adaptation is itself a process and not a target.

However, the conclusions from COP28 weren't wholly positive. For instance, the relationship between the GGA and other negotiation tracks that include adaptation remains ill-defined. It is not clear if talks around the Global Goal on Adaptation have consolidated or further fragmented negotiations. Currently, adaptation negotiation streams include the GGA, the Global Stocktake, the Adaptation Committee, the Adaptation Fund, and national adaptation plans. This fragmentation makes it harder to establish authoritative forms of governance that could remove ambiguity on adaptation provisions and concretely shape global adaptation actions.

Adaptation negotiations also fell short in other crucial ways. The trajectory of COPs has become somewhat predictable, with political hype and catchwords making way for to agreements on make-believe targets that countries will not achieve. COP28's outcomes on the GGA sadly fit this trend.

The heart of the GGA is supposed to be about ensuring effective participation by all countries to achieve agreed objectives on adaptation. As such, the African Group of Negotiators has consistently called for direct linkages between targets and provision of support - financial, capacity building, and technology transfer - for implementation.

I do not interpret this call as seeking a new dedicated fund as there are already at least five funds to address adaptation-related issues: the Loss and Damage Fund, the Adaptation Fund, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), and the Green Climate Fund (GCF). Neither do I see this call by the African Group of Negotiators as requesting "handouts" from industrialised countries.

Rather, I understand African negotiations position as: 1) asking to be more than mere participants in shaping global adaptation policy and having more than just "a seat at the table"; 2) recognising that the GGA process requires empirical data and not just anecdotal information, and acknowledging that African countries lack the financial and institutional capacity to collate such empirical data; and 3) seeking assurances that industrialised countries will ensure African contexts inform this critical global adaptation discourse.

The AGN did not receive these assurances. Sadly, by depriving African countries the opportunity to be active players in achieving the targets of GGA, industrialised countries have ensured that the continent will remain at the periphery of an agenda that is central to its development. This outcome effectively locates Africa as a consumer of framings and conceptual advances that will be provided by industrialised and the large emerging developing countries.

The former UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, once said that: "The recognition that the industrialised countries should take the lead in tackling climate change is one of the political cornerstones of the Convention." In the GGA negotiations at COP28, developed countries refused those responsibilities. Rather, they succeeded in transferring the burden of climate action to developing countries, including Africa and Least Developed Countries.

So much for fairness and justice in the much-lauded process of global governance of climate change. The COP28 outcome on adaptation provides yet another signal to African governments that the continent cannot, and should not, rely on industrialised countries for advancing an African climate agenda.

Dr Brian Mantlana is a commissioner on South Africa's Presidential Climate Change Commission and leads a team at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). He previously led the African Group of Negotiators in UN climate change negotiations for more than 10 years on several topics.