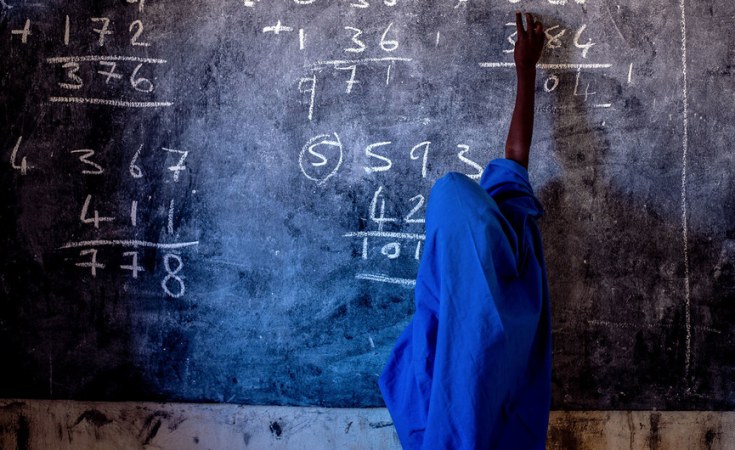

This is the African Union’s Year of Education , but for girls, we have yet to see bold action. Now is the time.

Last week, the AU hosted a high-level meeting in Addis Ababa to galvanize support for financing and action on the education of girls and women across the continent and remind governments of the goals of its Africa Educates Her campaign. This is one of numerous high-level gatherings organized by the African Union to spur education progress to meet its 2025 Continental Education Strategy .

There has been important progress across Africa: Over the last 20 years, primary and secondary school enrollment has increased across most of the continent. At least five countries have recently adopted ambitious measures – through laws, policies, or pledges—to expand free education from pre-school to secondary.

Keep up with the latest headlines on WhatsApp | LinkedIn

Yet, African governments have a lot more work to do. At least 51 million girls are out of school across Africa. Globally, 9 out of the 10 countries with the highest education exclusion rates for girls are in sub-Saharan Africa, according to UNESCO’s recent data.

adults... offer them money in exchange for sex. They know girls are highly vulnerable

The Addis Ababa meetings provided an important opportunity to set a clear human rights-focused agenda to tackle some of the most urgent issues that will safeguard girls and their right to education.

Consider three proposals:

First, guarantee that education is free, a core human rights obligation. Governments need to stop charging students extra-official tuition and enrollment fees, eliminate charges for school materials and school uniforms, and tackle other indirect costs such as school transportation.

Girls whom Human Rights Watch has interviewed across the continent have often told us that adults –whether teachers, bus or motorbike drivers, shopkeepers—offer them money in exchange for sex. They know girls are highly vulnerable: they need money to pay for their enrollment or exam fees, for transportation to get to school, or to buy menstrual pads so that they can go to school.

Second, prevent and manage the impact of unintended pregnancies on girls’ lives. Unintended pregnancies are one of the biggest factors fueling girls’ exclusion: in Africa, one in every five girls gets pregnant before they turn 19. Every year, tens of thousands of girls drop out or are forced out of school –most often against their wishes—because of discrimination, exclusion, and lack of support for girls facing unintended pregnancies. Girls are frequently denied the ability to choose what happens to them through their pregnancy, and once they are no longer pregnant, including when and how to return to school.

classmates and teachers had made it clear I was not welcome there because I was pregnant

There has been momentum among many African governments around the rights of girls who are pregnant or parenting to equal quality education. Still, in many of the 38 AU countries that have a policy on pregnancy and parenthood in schools, complex barriers hinder them from staying in school. Governments need to provide a clear route back to school, with needed support, and not leave the task to school officials or others who might not have the girls’ best interests at heart.

Mozambique is one example. We spoke to Anchia , 20, of Maputo, who said: “My parents had the conditions to send me back to school, but it was very difficult to focus on the lessons when classmates and teachers had made it clear I was not welcome there because I was pregnant.”

All African governments need to promptly adopt human rights-compliant policies to support girls to stay in schools and complete their education. They should give due consideration to the experiences and views of adolescent girls and women and learn from other African countries’ frameworks, including from those with social protection systems that include girls who are parents.

African governments should also commit to tackling the lack of access to reliable, understandable information and non-judgmental, evidence-based education about sexuality, reproduction, and gender-based violence, which are contributing to children, some as young as 12, facing unintended pregnancies. Schools have a crucial role to play in ensuring that children receive this information and to ensure that students have access to adolescent-responsive reproductive health services.

Third, and finally, governments should overturn regressive laws and policies that undermine girls’ and women’s rights. Recent moves by lawmakers in Gambia to reverse the prohibition on female genital mutilation is a prime example of negative measures that will thwart progress toward the African Union’s commitments. All African governments should reaffirm their commitment to upholding the continent's women's rights treaty, and ban FGM and child marriage in their national frameworks.

African governments should re-commit to delivering on these core issues for all women and girls across the continent.

Allan Ngari is Africa Advocacy director, and Elin Martinez , is senior children’s rights researcher, both at Human Rights Watch