Luanda — Over the past years, Angola has come to be governed less as a republic and more as a personalized system of power. What once functioned as a party-state has gradually evolved into something narrower and more concentrated: a president-state.

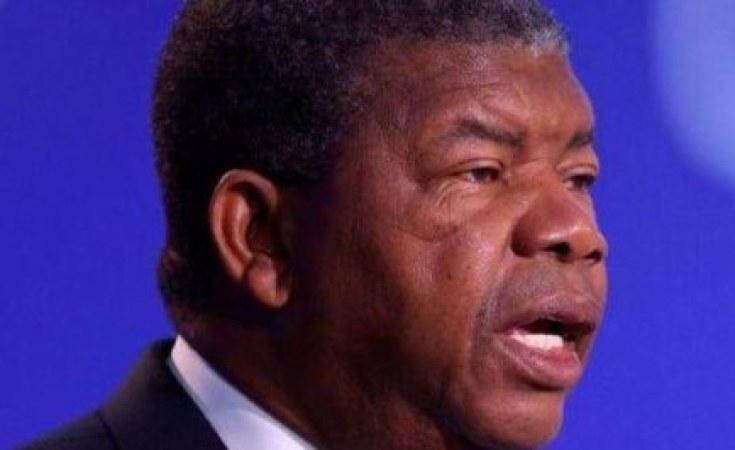

This transformation did not occur through rupture or overt authoritarian declaration. It unfolded quietly, through administrative practice, selective enforcement of the law, and the steady erosion of institutional counterweights. João Lourenço did not invent this system — but he consolidated and personalized it.

For decades, Angola operated under a party-state logic, in which the ruling party absorbed state institutions. Under Lourenço, that model shifted. The party was not democratized; it was subordinated. Decision-making migrated from collective party bodies to the presidency itself.

Keep up with the latest headlines on WhatsApp | LinkedIn

Today, the ruling party functions less as a space for deliberation and more as a mechanism of validation. Internal competition is discouraged, dissent is neutralized, and succession is carefully managed from above. The party survives, but as an instrument — not as a counterweight.

This personalization of power weakens both the party and the state. Institutions meant to mediate authority increasingly transmit it downward, reinforcing a system built on loyalty rather than accountability.

Angola is approaching a decisive political cycle. The ruling MPLA is expected to hold its party congress in 2026, ahead of general elections scheduled for 2027. While the constitution limits the president of the republic to two terms, the ruling party imposes no term limits on its leadership. Control of the MPLA thus becomes a strategic instrument to shape succession, pre-select candidates, and retain influence beyond formal presidential mandates.

At the same time, the Angolan government has benefited from renewed international legitimacy driven by external agendas, particularly around large-scale infrastructure and energy projects such as the Lobito Corridor. Promoted as a strategic transport and logistics hub linking Angola to the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, the project has reinforced Angola’s image as a stable and reliable partner. This external validation, however, has tended to mute scrutiny of internal governance practices and institutional erosion, allowing political consolidation at home to proceed with limited international challenge.

A defining feature of Lourenço’s Angola is governance by exception. Public procurement increasingly relies on direct awards rather than competitive tenders. Legal norms remain formally intact but are applied selectively. Accountability is proclaimed, yet due process is inconsistently observed.

The anti-corruption campaign illustrates this logic. Presented as a moral and institutional reset, it has operated unevenly — prosecuting some figures while shielding others, dismantling old patronage networks while enabling new configurations of power. Corruption is not eliminated; it is re-administered.

The judiciary, far from asserting independence, has been progressively drawn into this architecture. Legal institutions function less as checks on power and more as instruments within it. Separation of powers survives largely as constitutional language, not as political practice.

Internationally, Angola continues to be framed as a pillar of regional stability and a reliable strategic partner. Infrastructure projects, geopolitical positioning, and energy interests reinforce this perception. Stability, however, should not be confused with legitimacy.

Domestically, governance has grown increasingly detached from social reality. Official discourse emphasizes reform and progress, while living conditions deteriorate for the majority. Public frustration rises, yet institutional channels for expression remain weak, compromised, or deliberately constrained.

Elections persist, but they increasingly serve a procedural function: legitimizing continuity rather than enabling choice. Political participation becomes ritualized, while meaningful alternation recedes.

As Angola approaches a critical political horizon, the central struggle is no longer reform but succession. The objective is not institutional renewal, but control over the post-presidential landscape.

By reshaping party structures, neutralizing rivals, and maintaining leverage over key state institutions, the current system seeks to govern even beyond its formal tenure. Power is not being prepared for transition; it is being insulated against it.

This approach carries inherent risks. Systems built around personalization weaken the institutions required for stable succession. The more power is concentrated, the more fragile the transition becomes. What is gained in short-term control is lost in long-term resilience.

The fundamental question facing Angola is not whether one leader will be replaced by another. It is whether the country can move beyond a model in which the state is treated as an extension of individual authority.

Without genuine separation between party and state, without an independent judiciary, and without a revitalized civic and political sphere, leadership change risks becoming cosmetic. The face may change; the method remains.

The country of Lourenço is therefore not merely a portrait of one presidency. It is a mirror reflecting a deeper choice: institutional reform or prolonged personalization of power.

Angola’s future depends on whether it can reclaim the state as a public good — governed by rules rather than discretion, and accountable not to individuals, but to its citizens.