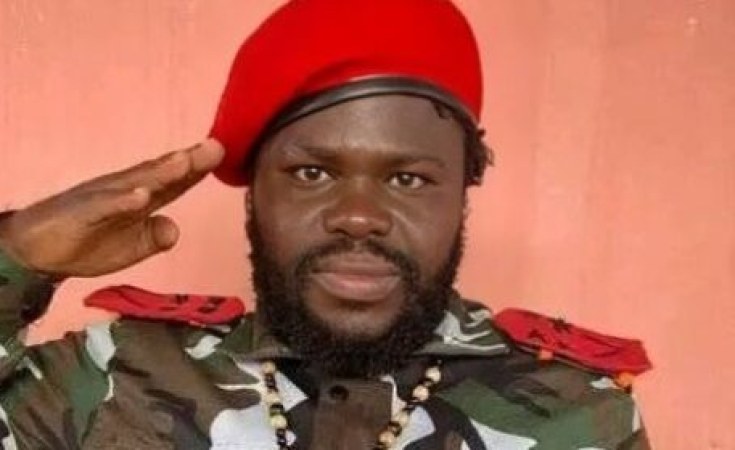

Detained on 28 July 2025 after being shot by police on the first day of Angola's taxi drivers' strike, Serrote José de Oliveira -- widely known as "General Nila" -- has been held for over six months without formal charges. According to his family and lawyers, he remains in detention despite a guarantees judge's order for his hospitalization and the rejection of a habeas corpus petition.

Earlier that morning, Nila was walking with his younger brothers, Bartolo and Pascoal, to Talatona Municipal Hospital to visit a hospitalized relative. His family says they were not participating in any protest and that there were no disturbances or acts of vandalism in the area.

It was the first day of the taxi drivers' strike in Luanda. According to figures released by the Angolan National Police, the protests and subsequent security operations resulted in at least 30 deaths, 277 injuries, and more than 1,515 arrests.

According to Bartolo's account, an officer of the Criminal Investigation Service (SIC) fired four gunshots behind them. "General Nila turned around to question the officer," Bartolo recalls. He says the officer then pointed the gun at his brother's chest and threatened him: "I'm going to kill you." Nila replied: "You can kill me."

Keep up with the latest headlines on WhatsApp | LinkedIn

Bartolo maintains that the officer intended to kill his brother, but that Nila managed to move as the weapon was being handled. The bullet struck his left foot instead. "Then he knocked him to the ground," Bartolo adds, stating that the officer fled the scene on a motorcycle.

The incident took place near Café da Vila, in the Vila do Gamek neighborhood, only a few minutes from the family home. Bartolo insists that there was no protest or tension at the location. "Everything was calm," he says.

According to the family, a SIC vehicle collected the injured man and transported him to Talatona Municipal Hospital. Shortly afterwards, a patrol of the National Police -- "with a high-ranking officer and several senior agents," according to Bartolo -- detained General Nila and took him to the Talatona police command.

Diana Rita Joaquim, Nila's wife, says that due to the seriousness of the injury, the police later transferred him to Camama General Hospital. During this period, she and her mother-in-law were able to visit and speak with him. "At 10 p.m. that same day, he was taken back to the cell, without having been discharged," she states.

The family emphasizes that up to that point, no formal explanation had been given for the detention.

Days earlier, on 17 July, the family had already been targeted in a joint operation by municipal inspectors and the National Police. According to Diana Joaquim, while her husband went to the municipal offices to respond to a notification, inspectors destroyed the kiosk that served as the family's small street bookshop, near Vila do Gamek.

"I tried to defend our rights," she says. Seven months pregnant at the time, she reports being pushed by a police officer with such force that she lost consciousness. "I only came to my senses when I was already hospitalized at Lucrécia Paim Hospital, where I remained for three days."

Diana adds that since then she has continued to face harassment by police officers in the Cantinton area, who repeatedly confiscate the books the family sells to survive. "We sell school textbooks, law books, novels, history books," she explains.

Serrote José de Oliveira presents himself as the leader of the so-called National Unit for the Total Revolution of Angola (UNTRA), which the family describes as an informal group of friends dissatisfied with the country's sociopolitical situation. According to Bartolo, the group's activities include organizing soup kitchens, distributing food to those in need, and joining protest marches in solidarity with other social causes.

"If someone commits an illegal act, we are the first to hand that person over to the police," he says. "We stand for order and peace."

Legal Framework: When the State Acts Outside the Law

The facts described by the family of Serrote José de Oliveira -- whose defense is led by Kutakesa --raise serious legal questions regarding the conduct of Angolan authorities, considering the Constitution of the Republic of Angola, ordinary legislation and the international commitments undertaken by the State. They illustrate a recurrent reality: the existence of laws is meaningless if those responsible for enforcing them -- police and magistrates -- are the first to violate them.

The use of a firearm by an alleged SIC officer against an unarmed citizen raises serious doubts about compliance with the principles of legality, necessity, and proportionality. The Angolan Constitution protects the right to life and physical integrity and obliges security forces to protect citizens.

According to Maka Angola legal analyst Rui Verde, the detention violated the Criminal Procedure Code, which limits detention to 48 hours and requires judicial oversight. By late January 2026, the statutory deadline to file an indictment in pre-trial detention had expired, meaning Serrote José de Oliveira should have been released. Angolan law does not criminalize dissent or peaceful protest. Yet when unarmed citizens are shot, detained for months without indictment, denied medical care, and deprived of any meaningful judicial remedy, the conclusion is unavoidable: the law is no longer being violated -- it is being deliberately set aside. What emerges is not a breakdown of the legal order, but its conscious replacement by a system where repression governs, accountability disappears, and illegality becomes the operating logic of power itself.