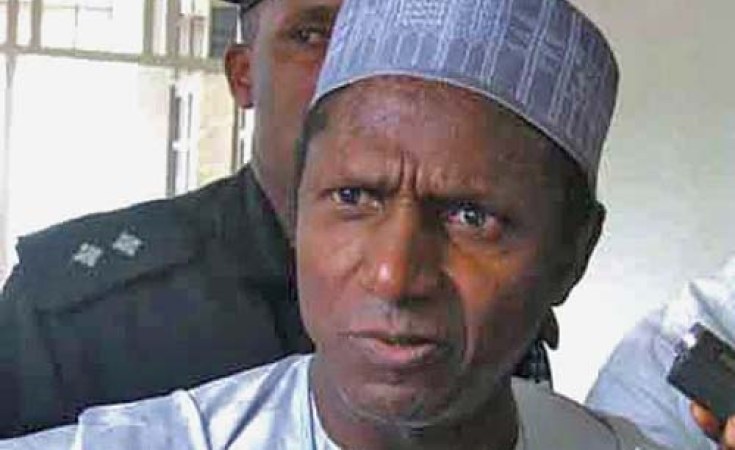

New York — Nigerians are getting startling, and conflicting, news each day about their long crisis of governance. Early Monday morning, the BBC's Hausa service surprised them with a three-minute interview with their long-absent, long-silent president, Umaru Yar'Adua, in which he said, "I'm getting better" and hoped that "very soon" he will be able "to get back home."

The day before, however, Nigeria's newspaper NEXT ran this headline on page 1: "Yar'Adua is brain-damaged. NEXT is standing by its original story, and its editors, and many other Nigerians as well, are demanding photographic evidence of his condition."

For all practical purposes, Nigeria, a country of some 150 million people, is still without a government, and Nigerians are forced to live in a tense, rumor-filled kind of limbo.

President Umaru Yar'Adua was hospitalized in Saudi Arabia seven weeks ago without following the constitutional requirement that he temporarily hand over to his vice president. Until Monday, Nigerian officials either remained silent or made statements few Nigerians believed: The president is recuperating, he will be home soon, he has been on the phone with other officials. During all that time, those tasked by the constitution to handle the succession declined to act. Yar'Adua's cabinet (whose jobs depend on him) has not been willing to set in motion the necessary machinery to replace him with Jonathan.

Into all this came the event on Delta flight 253 near Detroit on Christmas Day, which led the United States to place Nigeria, unfortunately, on a terrorism watch list. Farouk Abdul Mutallab's radicalization, after all, took place in London and Yemen and not in Nigeria. One by-product of Nigeria's governmental dysfunction is that in trying to find a constructive role it might play, either after this incident or on broader issues, the United States has had no high level, responsible official to talk to.

Islamic extremist incidents in Nigeria's north have occurred sporadically over the years, to be sure. But they are carried out by local groups and center on local grievances. No one has yet produced credible evidence of ties to al-Qaeda or its offshoots, though terrorism rumors surface at times. Some are floated by those who seek to attract US attention or curry favor for their own purposes. Indeed, paradoxically and distressingly, by placing Nigeria on its terrorism watch list, the US has handed alQaeda or its affiliates a potential recruiting tool in a place where, highly knowledgeable Nigerians speaking of their own communities will tell you, they have gained no serious traction.

Perhaps, though, the governmental stasis will soon end. The weeks of uncertainty have thus far been marked by groups of people—mostly present or former office holders--planning, plotting and maneuvering.

The succession is complicated by the fact that both Yar'Adua and his vice-president, Goodluck Jonathan, were effectively imposed on the country by the former president, Olusegun Obasanjo with his collaborators in the PDP, de facto Nigeria's sole political party in a theoretically multiparty democracy.

The weaknesses of both of them—health in Yar'Adua's case, inexperience in Jonathan's--were well known, and many Nigerians believe that Obasanjo chose them so he could exploit the weaknesses and continue to control the political process. Thwarted in that, he is undoubtedly one of those working to affect what happens now.

An additional complication comes through an informal PDP arrangement, whereby the office of president is to alternate between largely Christian south and the largely Muslim north of the country for eight years at a time.

But it is important to note that despite this, influential voices from the north have joined those from the south in insisting that the constitutional provisions must be followed if the president cannot fulfill the functions of his office—which means than Goodluck Jonathan, from the Niger Delta's Bayelsa State, must succeed Yar'Adua, from far northern Katsina State, as president for the rest of their four-year term.

With this emerging consensus, the key follow-up question is who would become vice president? Nigeria's constitution resembles its U.S. model, but introduces decidedly Nigerian differences, which create added complications. One of these is that when a vice president succeeds an incapacitated president, both houses of the National Assembly have to approve his choice of vice president. This brings all the intra-PDP machinations into play there, where the party has a substantial majority in both houses but with loyalties divided among many "godfathers."

So back to the plotting and planning. Two agendas, with contrasting goals, have emerged. One is for a northern vice-president who would become heir apparent to the 2011 nomination. Multiple groups, self-interested, are jockeying to produce the person (different in each case) who will most benefit them; this includes protecting them from future probes of their illegal activities in or out of office.

A second agenda, which is playing out more quietly behind the scenes, comes from some Nigerians, more concerned with the national interest than their own. Their goal is to find someone — also a northerner -- of maturity, experience, stature and integrity to be able to do two things: Assist a President Jonathan in dealing with the overwhelming problems Nigeria now faces, among the most urgent, the troubled economy and the fragile truce with insurgent groups in the Niger Delta. And second, put in place electoral reform, including democratizing the political parties. With national elections due in 2011, that reform, spelled out by a presidentially-appointed committee, is desperately needed to give Nigeria's battered democracy—in name only for a decade—a chance at last.

Meanwhile, Nigerians are at last starting to make their voices heard. Now, they may have one High Court judgment to install Jonathan, and several other cases are pending in suits filed a week ago. A demonstration making a similar demand took place Tuesday in Abuja, led by such notables as Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka; others are planned for Lagos and elsewhere. The House of Representatives says it will send a delegation to Jeddah to ascertain the state of the president's health.

If the situation gets even more chaotic, military intervention is always possible. Indeed, Nigerians' desperation with their plight is startlingly evident in some popular anger, openly expressed, that the army hasn't stepped in already. But it is unlikely: The military hierarchy must know that to move now would be seen as aimed at blocking a Jonathan—read "southern"—presidency, which could unleash widespread, unpredictable violence, not least in Jonathan's own Niger Delta.

The weeks ahead will be critical for Nigeria's future. Beyond urging that constitutional provisions be followed and the national interest be kept at the fore, there is little the United States government can do until Nigerians themselves work out who will take charge, and there is someone responsible to talk with.

Jean Herskovits, Research Professor of History at the State University of New York at Purchase, New York, has been visiting Nigeria for four decades, including three trips in 2009. An earlier version of this article was published on January 12 by foreignpolicy.com.