Witches camps in Northern Ghana continue to exist, as victims there still face harsh economic experiences and society still with the notion of they being a danger, and in spite of that, there has been good news about the camps' existence.

According to the Southern Sector Youth and Women's Empowerment Network (SOSYWEN), after numerous sensitisations by the organisation and other non-governmental organisations (NGO), there has not been any increment in the number of alleged witches in the various camps.

For SOSYWEN, if there is persistent education and help from the government and other NGOs, there is the possibility that the horrific violence and abuse against alleged witches in the region will be reduced, and if possible, families of victims will go and take their relations back home. Continued education of members in the various communities in the region will enlighten them about the issues of human rights, and lead to the eradication of this inhumane act in the communities. It is a good thing that the government has not totally forgotten about the plight of these inmates.

Witches camps in the Northern Region of Ghana

The need to insulate those accused of witchcraft from the wrath of society has occasioned the setting up of three camps in Northern Ghana. They are the Ngani camp in Yendi, the Kukuo camp in Bimbilla and the Gambaga camp. According to SOSYWEN, a non-governmental organisation which helps women whose rights have been trampled upon, the Ngani camp consists of 750 women and 400 children; Kukuo camp has 130 women and 171 children, while the Gambaga camp consists of 86 women and 36 children.

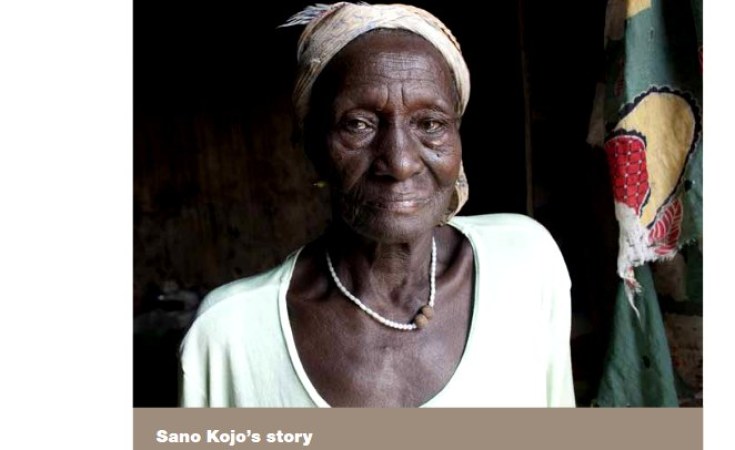

Inmates at the witches' camps

Older women, who have mostly passed their menopausal period and can no more take care of themselves, are the group of people society mostly accuses. Having no concerns about the contribution of these women to their various families and societies, people, mostly their siblings, husbands, children, and in-laws are those who accuse them of being witches. The children in these camps sometimes happen to be the grandchildren of the inmates, and according to sources, these children follow them there, since they may be orphans and have no one to take care of them. These children help the inmates, in terms of water supply, errands and on their farms.

According to sources, most of these inmates fear returning to their communities, because they would either be brutally beaten or even killed by mobs. In view of this, the inmates prefer to stay the rest of their lives in the camps for security. When they die, they are sometimes buried in their huts.

According to SOSYWEN National Coordinator Zenabu L Sakibu, experience has shown that even in the rare cases that an accused woman is accepted back, it can take 5-10 years of sensitisation efforts before the community will agree to it. She may be confined to her own home and never allowed to leave her compound.

Government activities for the witches' camps

About three months ago, the National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO) donated to these camps. Recently, it was reported in the Ghanaian Times newspaper edition of November 18, 2011, that the Minister of Women and Children's Affairs (MOWAC) Mrs. Julian Azumah-Mensah, had announced the disbandment of these witches' camps.

The Ministry plans to collaborate with local opinion leaders and others to halt the practice of witchcraft accusations and sensitise the communities so that women are accepted back by their families. According to SOSYWEN, they are pleased with the concerns the government has for inmates of these camps, however, they also believe strongly that such a disbandment is a wrong response to the problem, and reveals a lack of understanding of how deeply engrained the beliefs in witchcraft in these communities, and how difficult it is to encourage them to accept accused "witches" back home.

Disbanding the witches' camps before sensitisation effort might not prove successful, it will make the women homeless, since they won't be accepted back by their families. Women accused of being witches and banished to a life in the witches camps face hardship, desperate poverty and deplorable living conditions.

For SOSYWEN, these victims should at least be given some shelter, limited access to food and water, and the company of other women. If the camps are disbanded too soon, they will lose even the limited access to these few comforts and means of survival.

Suggestion of SOSYWEN to the Government

In view of the consequences that will befall the inmates should the camps be indeed disbanded, SOSYWEN urges the government that it should strengthen the capacities of the Police Service and the Judiciary to deal with the violation of women's rights swiftly and effectively, to deter others from accusing and violently abusing more women.

The government should provide basic necessities in the camps, such as potable water sources, health insurance cover, and insecticide treated bed nets to make women's lives more bearable.

Moreover, it should set up a transition committee, made up of various organisations (including women in these camps) who have been working on the witches camps, to advice on the best way to phase out these camps.

The organisation further urges the government put in place a longer term strategy to abolish the witches' camps, and ensure that any cultural practice that dehumanises women has no place in society today.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of witchcraft accusation is a gender balance issue, as women are those who always find themselves at the receiving end. As there is no section in the constitution defining witchcraft as a crime, it is therefore, a human rights abuse to subject an individual to such cruelty.

It is up to the Domestic Violence and Victims Support Unit (DOVVSU) to save inmates of these camps, and future inmates as well, as society is making no effort to prosecute culprits of these brutalities, or report them to the authorities. DOVVSU can take it upon itself to monitor these communities, in order to arrest the perpetrators of such activities when the need arises.