Nicholas Mphangwe, known to his friends as Nick, works as a plant breeder for the Tea Research Foundation of Central Africa, in Malawi. Tea is critical to the Malawian economy, accounting for about 30 percent of the country’s foreign exchange and about 5 percent of the world’s tea crop. (India, Sri Lanka, and Kenya share equally about 70 percent of the world market, with the rest scattered among Uganda, Malawi, South Africa, and a few other producers.)

Producing tea, like other agricultural activities, has become a high-tech enterprise, requiring advanced skills. Nick has honed his skills with a BS from the University of Malawi and a master’s from the University of East Anglia, earned in 1996; he has worked at the Tea Foundation ever since. But his mentor, chief plant breeder Dr. Hastings Nyirenda, is preparing for retirement and has urged Nick to move one more step up the education ladder to take his PhD, which Nick has been eager to do.

Unfortunately, the expense of such an undertaking have held him back for years. Even with the relatively low tuitions in African graduate programs, Nick was facing about $2,000 a year in tuition costs, another $4,000 in living expenses, and about $4,000 in bench fees (biochemistry is expensive!). Although the Tea Foundation has been generous in funding research, its income has declined in the past few years. A major contributor, Zimbabwe, has virtually disappeared as a tea producer, its 200 or so farms abandoned, its untended tea plants growing wild in the fields. Tea production generally has sagged worldwide during the current recession.

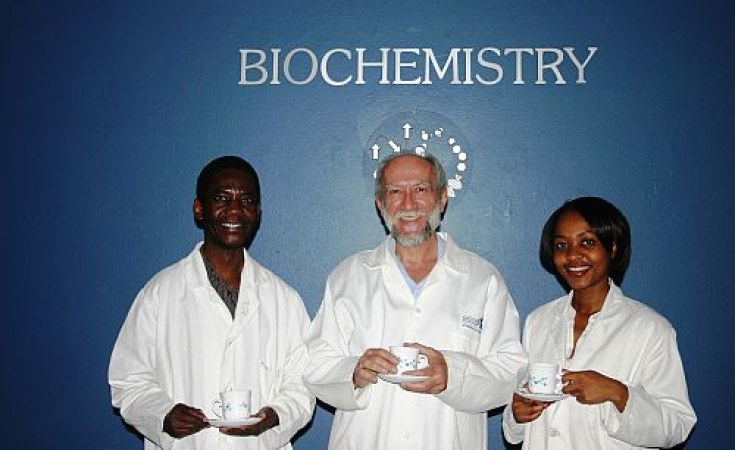

Luckily for Nick, a long-time collaborator, Prof. Zeno Apostolides of the University of Pretoria in South Africa, recently became a faculty advisor in RISE’s network on biochemistry and bioinformatics, SABINA. He called Nick, who applied to the program and was accepted. Because a main thrust of the RISE program is to help build advanced scientific skills, especially for people who are already experienced and committed to a field of their choosing, Nick was an ideal candidate.

One area of skills needed by Nick – and by the Tea Foundation – is the ability to identify genetic markers that will allow for more accurate and rapid selection of desirable tea strains. The scientists at the Foundation have been raising and studying some 300 tea cultivars, seeking to improve quality by traditional methods of hand selection. Nick hopes to help refine this process through the use of genetic markers for such desirable qualities as taste, resistance to insects and diseases, tolerance of low temperature and drought, and reduced caffeine.

While the University of Malawi supports extensive studies of many plant crops, Pretoria offers a particular focus on tea, supported by well-equipped labs. One challenge is to analyze some 30 different components of tea; Prof. Apostolides is especially proud of a new high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) machine that allows a new level of accuracy in separating, identifying, and quantifying plant compounds. Nick will also be able to work in the Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Unit, where he can explore the activity of key metabolites of tea. SABINA budgets sufficient funds to allow Nick to take full advantage of the tools and people at Pretoria without drawing down his own savings, making available a range of advanced biochemical and genetic skills.

Meanwhile, there are signs that during his absence of several years the fortunes of the Tea Foundation may improve. In Zimbabwe, small numbers of entrepreneurs have begun to return to the abandoned tea plantations, pruning and tending the once-abandoned plants and laying the groundwork for a renewed industry. If this trend persists, the country may once again be able to harvest and sell this important crop, resuming its contributions to the Tea Foundation and to modern programs that enhance the pleasure of tea-sippers worldwide.