Ghana's handover has been smooth, others have not. What is the lesson?

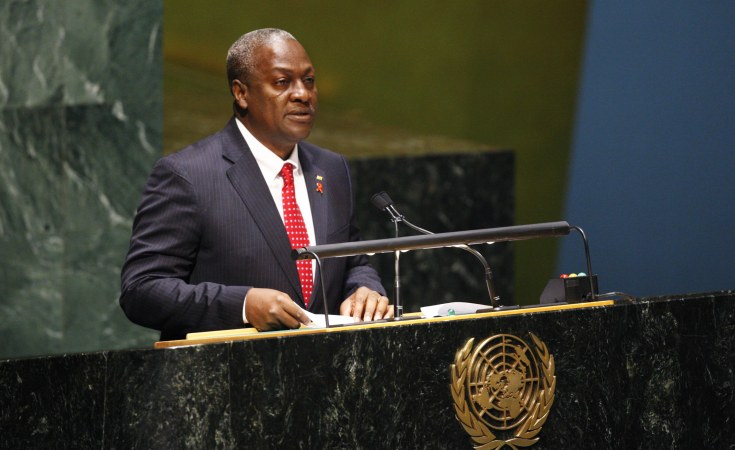

The death of Ghanaian President John Atta Mills led to the swift elevation of his vice-president, John Dramani Mahama, to the presidency. Mills, who has been suffering from throat cancer, was rushed to hospital on Monday evening and died the following day. Mahama was sworn in as his successor within hours, taking the oath at an emergency parliamentary session.

This smooth and orderly transition - so far at least - has been widely celebrated. The mature reaction to John Atta Mills' death has served as an indicator of the strength of Ghana's democratic culture, and has raised obvious contrasts with events in other countries in which an incumbent president has died mid-term. Here, Think Africa Press looks at how other African countries have coped with the recent deaths of incumbent presidents.

Nigeria: Jonathan tests north-south tensions

The death of President Yar'Adua in 2010 was not unexpected. Ever since rise to the presidency in the heavily disputed 2007 election, there had been rumours of his ill health. In November 2009, Yar'Adua left Nigeria for Saudi Arabia to seek treatment for pericarditis.

After a dangerous limbo period of over two months, the senate determined that presidential powers could be transferred to Yar'Adua's vice-president, Goodluck Jonathan. However, although the initial transition went reasonably smoothly, profound divisions within the ruling People's Democratic Party (PDP) soon became clear. The critical issue was the PDP's 'zoning' policy, in which the presidency alternates between northerners and southerners. After two terms of southerner President Olusegun Obasanjo, northerners expected they would also enjoy two terms in the presidency - if not under Yar'Adua then under another northerner.

But Jonathan, who is from the Niger Delta in the country's South, managed to complete Yar-Adua's term, successfully pursued his party's presidential nomination, and last year won elections for the presidency. In the context of Mills' sudden passing, the quality of the 2011 elections could prove Jonathan's enduring legacy. Between Yar'Adua's death and the April 2011 elections, Jonathan strengthened the electoral commission considerably, placing the widely praised and respected Attahiru Jega at its head.

Whilst certainly not flawless, elections in Nigeria since Jega's appointment and the reforms to voter registration have been significantly more credible than their 2007 nadir. These improvements and existence of an independent arbiter - though not yet as notable as their Ghanaian equivalents - bodes well for the future of Nigeria's perennially precarious democracy.

Zambia: Opposition leader takes the initiative

Unlike in Nigeria, the Zambian constitution stipulates that a presidential election must be called within 90 days of an incumbent's death. When President Levy Patrick Mwanawasa died in August 2008, two years into his second five-year term, an election thus soon followed. The interim period between Mwanawasa's death and the election was largely calm, helped by the fact Michael Sata, the chief challenger to the ruling Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) party, both praised Mwanawasa and called for the constitution to be respected.

The MMD selected Rupiah Banda, Mwanawasa's vice-president and acting president upon his death, as its nominee without much debate. Sata, his main opponent, had heavily criticised Mwanawasa in the 2006 election, but now invoked his legacy, even claiming to have had a deathbed conversation with him. Although Banda clung on for a narrow victory, Sata's skilful use of Mwanawasa's death had greatly increased his support base, something he exploited in the 2011 election when he finally became president.

Malawi: the constitution survives, just

Malawi's democratic credentials were in doubt when President Bingu wa Mutharika died in office in April this year, following increasingly rash and autocratic actions from the president over the preceding 18 months. Mutharika is believed to have died from a sudden cardiac arrest on April 5 although, as with Yar'Adua, the exact circumstances of his death are shrouded in considerable mystery. His death was not officially announced for two days.

Mutharika succession was already a hugely controversial issue. His vice-president, Joyce Banda, had been expelled from the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) after refusing to accept Mutharika's alleged attempts to ensure his foreign minister brother, Peter, succeeded him as president in 2014. In response, Banda had formed the opposition People's Party in 2011 and was linked to pro-democracy protests in the summer of 2011.

Nevertheless, on Mutharika's death, the constitution decreed that Banda should become president. Members of Mutharika's cabinet, however, launched desperate attempts to prevent this transpiring, notably seeking a court order to obstruct Banda. These efforts failed and, aided by former Malawian President Bakili Muluzi, Banda was sworn in as president on April 7.

So far, Banda, Africa's second female president, has been praised for her rolling back of Mutharika's authoritarian tendencies for the presidency, curbing extravagant spending on cars and a private jet. These actions and her following IMF economic prescriptions, long resisted by her predecessor, have made her a donor darling. It remains to be seen whether her combination of liberal democratic social and political policies and donor-led economic policy will bear fruits before she has to stand election in 2014.

Ghana: Smooth so far

The most fundamental explanation for the initial success of Ghana's transition so far concerns the country's democratic maturity. Ghana has held five presidential elections since democratisation in 1992 - each being recognised as progressively more democratic. Moreover, the victory of opposition parties in 2000 and 2008 means Ghana is one of the relatively few African countries to have successfully passed Samuel Huntingdon's 'two turnover' test.

With a judiciary and electoral commission widely praised for their impartiality - which is helped by the fact there are checks on the president's powers of appointments over these - and a constitution that clearly lays out what should happen in the event of a president dying mid-term, Ghana's smooth transition should come as little surprise.

It is at the level of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) party that John Atta Mills' death could be more troublesome, however, given the NDC's constitution does not stipulate what should happen in the event of a presidential nominee dying.

The Rawlings family - former president and NDC founder Jerry and wife Nana - could conceivably consider that Mills' death provides an opportunity for them to reassert their authority over the party. However, the NDC has developed into much more than a mere expression of the Rawlings' political interests.

Ultimately, as with the country as a whole, the NDC should be able to withstand complications caused by Mills' untimely death.

Tim Wigmore is a freelance journalist who has written for The Sunday Times, The Independent, The Guardian and ESPNcricinfo, among others. His main interests in Africa are democratisation, with Ghana, Kenya and Zambia particular interests. He can be followed on twitter @timwig