Washington, DC — On Thursday the former soldier who seized power in Burkina Faso 27 years ago agreed to negotiate with opponents. The announcement was a response to massive popular demonstrations against President Blaise Compaore’s intention to extend his rule for another term. While most protesters were peaceful, violence left Parliament and other buildings in flames. Amid reports in the evening that the military had taken over in what amounted to another coup, social media celebrated that some soldiers had joined the protestors in the streets. Ambassador Johnnie Carson argues that the international community should press for democracy in this volatile period.

Democracy is on the line in Burkina Faso, a poor landlocked country on the edge of the Sahel, and what happens there may be felt across the continent. The stakes are high.

The outcome in Burkina Faso over the next weeks and months could influence whether democracy continues a positive trajectory across sub-Saharan Africa or whether it stalls or – worse – begins to unravel and collapse. Nations that follow democratic norms need to speak out clearly against African leaders who seek to change their government structures in order to retain power indefinitely.

For the past week, tens of thousands of people in Burkina Faso have taken to the streets of their hot and dusty capital, Ouagadougou, to protest a planned Parliamentary vote. Supporters of long-time President Blaise Compaore want to alter the country’s constitution to allow him another term in office.

Compaore, a former solider, came to power in a 1987 military coup d’état. Since abandoning his uniform and opening the door to multiparty politics and constitutional rule, Compaore has been elected five times as the country’s president. Until recently, he said that he would abide by the country’s new constitution and step down at the end of his current term which ends in 2015.

However, with elections fast approaching and his thirst for power still strong, Compaore has changed his mind and decided to “modify” the constitution to run for at least one more term. Parliament, dominated by Compaore stalwarts, must approve the constitutional change by a two-thirds vote, or the issue will go to a public referendum. Either way, Compaore seemed determined to get his way despite the massive protests.

One power grab begets another

The Burkina president’s attempted power grab may appear without implications beyond the small nation of 17 million people, bordered by six countries. However, if Compaore succeeds in manipulating and subverting the constitution, there are perhaps half dozen African leaders waiting in the wings who will try to do the same.

Leaders in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Gabon, Congo-Brazzaville and Benin all face strict two-term constitutional limitations. It is believed that DRC President Joseph has already signaled his desire to alter his country’s constitution before presidential elections next year. There are reports that President Denis Sassou Nguesso in neighboring Congo-Brazzaville may do the same, and Rwandan opposition leaders have speculated that President Paul Kagame in Kigali may attempt the same ploy.

The argument for long-term rule fails reality test

African leaders who remain in power for long periods of time claim that their leadership helps to foster stability, democracy and economic growth. But that statement does not align with the facts. Countries where heads of state remain in power for two or three decades exhibit similar and negative characteristics. Their governments become increasingly more corrupt. Human rights abuses expand. Press freedoms are curtailed. And political space for civil society, non-governmental groups and opposition parties begins to disappear.

When these aging regimes collapse, they frequently generate long periods of political tension, violence and uncertainty.

In Angola, where President Eduardo Dos Santos has been in power since 1979, corruption is rampant. The government’s state-owned oil industry is regarded by some as a slush fund for senior members of the ruling party and the president’s family, including his forty-year-old daughter Isabel, who is reported to be the richest woman in Africa, worth two or three billion dollars.

The same is true in Equatorial Guinea, where President Teodoro Obiang has ruled for 35 years. Obiang’s family has squandered millions of dollars of the country’s oil wealth, while much of the population continue to struggle in deep poverty.

In Zimbabwe, where Robert Mugabe has been in power since April 1980, human rights abuses and harassment of opposition political leaders has been a common occurrence for much of the last decade.

In Cameroon, President Paul Biya has been in office for just over three decades. Once hailed as the Switzerland of Africa because of its rich African, Anglo-French culture, Cameroon has struggled economically and politically. As corruption has flourished inside his own government, Biya has kept a tight leash on opposition politics and civil society activism.

And in Uganda, President Museveni, in charge since 1987, leads an aid-dependent government that has been accused multiple times of corruption, including the misappropriation of millions of dollars intended for HIV and malaria prevention. Like the other multi-decade leaders, Museveni has intimidated, harassed and beaten opposition political leaders and has punished and pushed aside those in his inner circle, like former Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi, who seek to encourage political change at the top.

The attempt of African leaders to remain in power indefinitely is an affront to democracy and to the rights of their own people. It is also an affront to the Obama administration’s policy toward Africa.

Shortly after he became president in 2009, President Barack Obama told members of the Ghanaian parliament in Accra that strengthening democratic institutions and promoting the rule of law were his number one policy priority in Africa. He said: “In the 21st century, capable, reliable, and transparent institutions are the key to success - strong parliaments; honest police forces; independent judges - an independent press; (and) a vibrant private sector…(and) civil society. Those are the things that give life to democracy, because that is what matters in people's everyday lives.”

Recognizing how many of Africa’s past leaders had abused power, President Obama told the parliamentarians that “Africa doesn’t need more strong men, it needs strong institutions.”

Over the past five years, the U.S. administration has reaffirmed this stance. In June 2012, the White House issued a comprehensive policy document reaffirming that the administration’s number priority was “strengthening democratic institutions.” The document said that “support for democracy is critical to U.S. interests and is a fundamental component of American leadership abroad. …The United States will not stand idly by when actors threaten legitimately elected governments or manipulate the fairness and integrity of democratic processes, and we will stand in steady partnership with those who are committed to the principles of equality, justice and the rule of law.”

And in the run up to August 2014 U.S. Africa summit, National Security Advisor Ambassador Susan Rice applauded Africa’s democratic progress and told a largely African diplomatic audience that the administration remains "unabashed in our support for democracy and human rights."

"We will continue to invest in promoting democracy in Africa, as elsewhere, because, over the long-term, democracies are more stable, more peaceful, and they’re better able to provide for their citizens,” she said.

President Blaise Compaore asserted that he could bring the peace, stability and economic prosperity that the people of Burkina Faso want. But the people of Burkina Faso, familiar with Africa’s long history of “strong man politics”, voted with their feet by protesting.

France, the former colonial ruler of the country then called Haute Volta, or Upper Volta, along with the United States and the European Community, should reiterate strong support for democracy in Burkina Faso, which means ‘land of upright people’.

African leaders who believe in democracy and the rule of law should also speak out. If autocrats parading as democrats can stay in power indefinitely, all of Africa will lose.

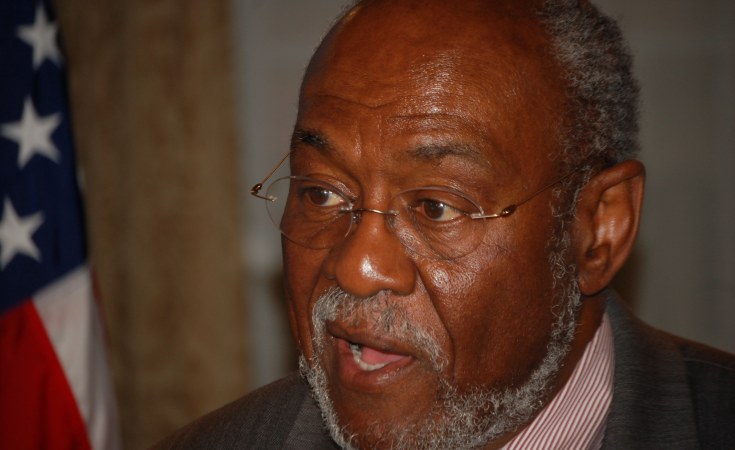

Johnnie Carson, a career diplomat who served as U.S. ambassador to Zimbabwe, Uganda and Kenya, was the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Africa from 2009 to 2013 during President Obama's first term. He currently serves as senior advisor to the President of the United States Institute for Peace.