When I immigrated to the United States from South Africa towards the end of the 1960's I was totally unaware of the wars of liberation against Portuguese colonialism that had begun in the early 1960's in the neighboring countries of Mozambique and Angola. All I knew about Mozambique was the reputation of its capital, Lourenço Marques, as a cosmopolitan Portuguese-style city where white South Africans went on holiday.

I had grown up in a staunchly anti-apartheid family and my hatred of apartheid was the main reason for leaving. When I arrived in the U.S., I entertained the notion that if average peace-loving Americans could only understand the repressive and brutal nature of apartheid, they would be so outraged they would pressure their own government who in turn would pressure the South African government to end apartheid. I was quickly disabused of my naiveté by the members of the Southern Africa Committee, a small anti-apartheid and solidarity organization which I joined soon after arriving, who viewed U.S. complicity with apartheid as self-evident. I was now learning that trade wasn't simply trade; that U.S. corporate investment and bank loans played a critical role in expanding the South African economy and bolstering the apartheid system. U.S. corporations were reaping huge profits by investing in South Africa while the regime grew strong and ever more repressive.

I began editing a small magazine published monthly by the committee. It would later lead me into journalism, resulting in invitations to the liberated zones of Guinea-Bissau in 1974, newly independent Guinea-Bissau in 1976, and post-independent Mozambique through the 1980s. My subsequent books focused on the impact of the revolutions and post-independence on women in these two countries.

Keep up with the latest headlines on WhatsApp | LinkedIn

For those of us working in the anti-apartheid and divestment movement in the 1970s and 1980s it seemed easy to write history forward. We harbored dreams and hopes. When the Portuguese colonies won independence in 1974 and 1975 and Zimbabwe in 1980 we were filled with a sense of possibility. We felt confident that the ideology of the liberation movements would, if not ensure, then contribute to national reconstruction based on far-reaching social and economic transformation and devoid of the corruption and tyranny plaguing many African countries independent since the late 1950s and early 1960s.

We studied the writings of brilliant thinkers such as Amilcar Cabral, founder and president of PAIGC, the liberation movement of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. One of the benefits of living in New York was the regular visits by leaders of these movements who had observer status at the United Nations. It meant I met Cabral, literally sitting at the feet of this great man at a meeting with solidarity group members in a friend's living room shortly before he was assassinated in 1973. With seeming ease, he could turn complex ideology and political analysis into simple words that gave us the wherewithal to argue the importance of solidarity with their struggle. My copy of his Revolution in Guinea: Selected Texts was held together with elastic bands, the spine cracked and unglued from use. What he said about the aim of the struggle stayed with me over the years. He insisted that people were not fighting for ideas, for things in anyone's head. "They are fighting to win material benefits, to live better and in peace, to guarantee the future of their children." This is what gave the revolution its meaning.

Looking back in the harsh light of current history we see a very different picture. I look for symbols, stories, that will provide a barometer for change. South Africa is where I return again and again, trying to figure out, after all these years, what "home" means to me and trying to understand what the newly democratic nation means to its citizens. My notion of "home" has been resolved. The richness of my life is that there are a number of places I call home because of the communities I have established there. What has not been resolved is how the not-so new South Africa will benefit those who know it as their only home. One way I chart change is through my friendship with Kate Ncisana who I spend time with on my fairly regular visits back to Cape Town.

On a windy but sunny afternoon four years ago, Kate and I stroll through the Company's Garden in the center of the city. I admire the verdant flower beds and shrubs. I take in the soft scented air. I remember walking there as a child, a white privileged child, when I was just becoming aware of the gross inequality and brutality of apartheid that bound us all in its unforgiving grip. Except it was a grip aimed at protecting me and the small percentage of South Africans who were white, while it wound itself increasingly tightly around the lives of the majority of South Africa's people. Now some twenty years after South Africa became a democracy, I can walk freely with this African friend who lives in Khayelitsha, a vast mostly shanty-town sprawl of poverty on the edge of the most beautiful city in the world. Kate and I sit on a bench to talk as cheeky squirrels come close to demand peanuts we don't have and doves provide a background music of rhythmic cooing.

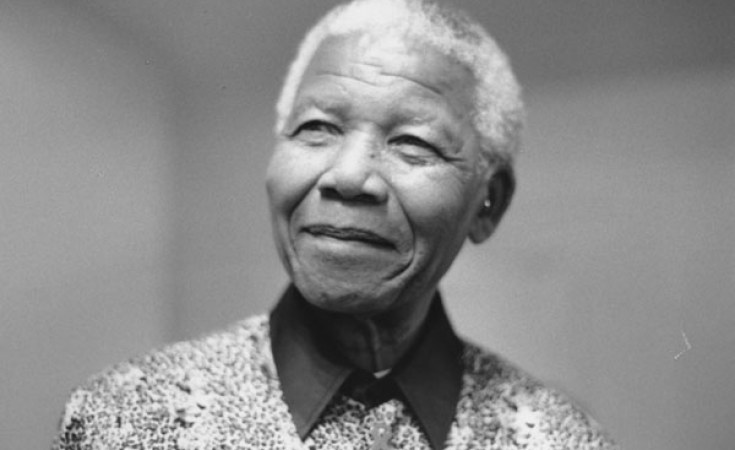

I first met Kate in 2011 in Khayelitsha when I interviewed her and other members of a group of fifty-seven, mostly women, who in 1982 staged a twenty-three-day hunger strike at St George's Cathedral in Cape Town against the pernicious pass system which restricted their movement and ripped families apart. They had entered Cape Town illegally in order to reunited with their families and to find work. Their protest helped end the pass laws a few years before the downfall of apartheid itself. In April 1994 Kate joined in the dancing and partying in the streets of Khayelitsha to celebrate the inauguration of President Nelson Mandela. Her joy was unbounded, her hopes high with the prospect of a better life to come. Now, seventeen years later, she and others from the Cathedral protest, sit with me in a semi-circle in a small community center, recalling that time and talking about their disappointments. They are still waiting for that better life, they say. They wait for basic services. I already know that twenty-three percent of Cape Town's household live in informal settlements but are allocated one percent of the city's water; fifty-two percent of Khayelitsha's youth face unemployment. They may not be familiar with such figures, but they know the impact.

I am in familiar territory -- the journalist, sitting poised with a pen and paper, a white among Africans. I have played this role in Guinea-Bissau and in Mozambique and other African countries I have written about: listening to women tell their stories. But this time I am not in a foreign country. My pen freezes above my notebook. Who am I really at this moment? A Capetonian wanting a sense of the complexity and diversity of the city I was born and raised in? Am I simply the recorder of stories for a book I am writing that are not mine? That's obviously the point but I can't help but feel more than a tad voyeuristic. I am reassured by the eagerness with which the women tell me about their lives – as activists and resisters, as full citizens of a democratic South Africa. They trust that I will convey their stories well. It is a weighty responsibility but as I absorb this a thought surfaces: these may not be my personal stories, but they are the stories of South Africa. We are all part of the crazy patchwork that makes up the tale of my country. As I return to their vivid telling I feel welcomed and my discomfort vanishes. But not my acknowledgement of my white privilege.

It gets late and the stories wind down. Kate sums up the mood of the group: "Apartheid is over but our struggle is not."

Four years later, sitting with her on the park bench, the bright sun filtering through the leaves, I ask, "How are you doing, Kate?" She shakes her head. She is still making beautiful beadwork. She has brought me a necklace which I finger like worry beads as I listen to her. Her daily life is good, she says. I am aware that a little bit of light has gone from her gentle, lovely face. She shakes her head ever so slightly at the deeper intent of my question given the state of South Africa. President Jacob Zuma is casting a shadow on our conversation. "If I had known what South Africa would become I would not have fought so hard against apartheid," she says. I have no answer. I just listen.

As I did once again a few months ago. This time Kate and I meet at an NGO office in Mowbray, a suburb where I lived until I was eight. It is now a diverse suburb, more black than white. Before I meet her, I walk down the quiet side streets, past my old house, buried behind a high wall, and look up at the magnificence of Table Mountain whose beauty was the cause of much nostalgia while apartheid kept me in exile. I take deep, satisfying breaths. I feel at one with the streets; every corner I turn brings back memories. I snap photo after photo.

Sitting with her in the conference room over cups of tea, I ask Kate what she thinks of the new president, Cyril Ramaphosa. It is the question I ask repeatedly this visit of friends involved actively in political life, both black and white, of Uber drivers, of everyone I speak to. The responses vary from cautiousness to optimism. Certainly, all are pleased to see the end of the Zuma presidency. But is Ramaphosa seriously willing to tackle poverty and improve the lives of the majority of South Africans such as Kate's? And if so, will he be able? She shakes her head. So much bad has happened, she is not sure how it can change. She is firmly in the "wait and see" camp.

I give her a copy of my memoir. She calls me the next day. "I couldn't sleep last night and it's your fault!" She is laughing. "I couldn't put it down." She calls again the day after. She has finished it. She thanks me for the book and what I wrote about her and South Africa. I thank her for her response. "It means a lot to me," I say. I think back to my doubts when listening to the stories of the group at the community center in Khayelitsha. Publishing a memoir is hard. And when it is finally published, it feels exposing. There were certain people whose opinions I had waited for with some anxiety. One of them was Kate's.

When people like Kate express their caution about the future of South Africa, I think back to those days when we believed that change in southern Africa and Guinea-Bissau would provide models for the world. I think of Cabral's assertion that revolutions are fought to win material benefits and guarantee the future of the children. It didn't turn out that way.

And yet as disappointed as we might be by the outcomes of the revolutions in the southern Africa, angered as we may be by the pervasive corruption, the state capture, and the failure to ensure material benefits for those denied them under apartheid, there is still much to learn from these independence struggles and the victories they won. I am not one to give up hope. What I do know, despite the sobering international reality right now, is that a determined people cannot remain crushed forever. When the people rise up, victory can be theirs.

Stephanie J. Urdang is a journalist and former advisor on gender equality and on gender and HIV/AIDS for the United Nations. She is the author of a memoir, "Mapping My Way Home: Activism, Nostalgia, and the Downfall of Apartheid in South Africa" from which this column is adapted. She was born in South Africa and lives in the U.S.