Twenty kilometers above the ground, giant balloons are hovering in the sky, providing high-speed internet spanning 50,000 square kilometers across central and western Kenya, with spillover to parts of Ethiopia, Rwanda and Uganda.

These balloons are part of an initiative by Google's Project Loon and Telekom Kenya. Although this project has been long in the making, it was fast-tracked by the Covid-19 pandemic.

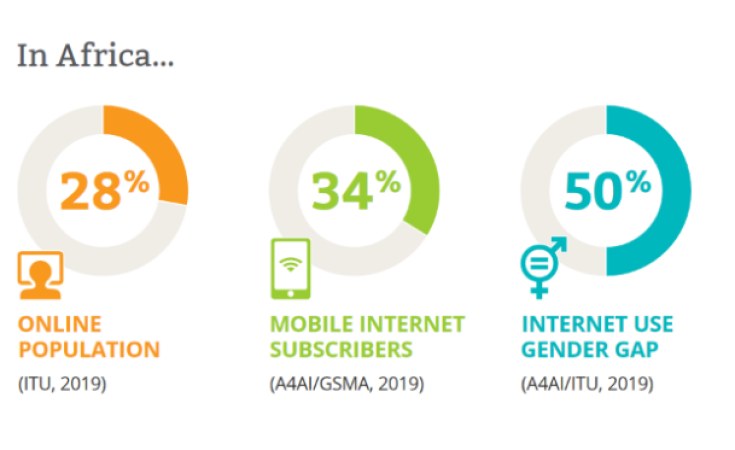

This is greatly needed as Internet access is poor across Africa. Alliance for Affordable Internet reports that about 28% of Africans have access to the internet. However, the statistics vary by country: 20% in Kenya, 26%in Rwanda, 18% in Ethiopia and 40% in Nigeria.

In addition to the low internet penetration in Africa, low internet speed is another major impediment to connectivity on the continent. It is expected that the Google Loon project will address both challenges.

To have an even greater impact, we propose the following ways to leverage Google's Project Loon and improve epidemic preparedness across the regions it will reach.

Digital collection can increase response time for a range of infectious diseases

Detection, prevention and response to infectious disease outbreaks begins with proper documentation, and the availability of high-speed internet through the Google Project Loon could help Kenya and neighboring east African countries transition from paper-based data collection of Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) to digital real-time platforms.

IDSR framework covers 41 notifiable diseases including Lassa fever, malaria, polio, tuberculosis, measles, yellow fever, HIV etc. It also reports maternal deaths, malnutrition, diabetes and road traffic accidents.

Digital collection through Google Project Loon would increase the response time to infectious diseases. The open-source SORMAS software already used by the Ghana Health Service and Nigeria Centre for Disease Control can also be deployed in Kenya to capture IDSR data.

Other infectious diseases captured under IDSR include a set of diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis known as Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs). These are a group of diseases affecting about 1.5 billion of the world's poorest people, mainly in Africa and Asia.

For several decades, the global health community has been battling to eradicate NTDs, and a way to keep track of eradication activities include mapping progress. Mapping NTDs in the field requires frequent live information sharing made possible by regular high-speed internet, so with Google Project Loon could make this effort more effective.

When programme managers know the burden, they can prioritize areas of need and reallocate resources accordingly. In Rwanda, a community-based mapping survey conducted in five districts previously known to be endemic for lymphatic filariasis eventually showed that it is no longer a disease of public health importance.

High-speed internet can enable real-time training for health workers and for community-awareness outreach.

Of course, to efficiently deploy IDSR requires that health workers are trained and retrained. It is easier for those working in cities to be trained. However, training health workers in hard-to-reach and remote communities has always posed a huge challenge. Some projects have attempted to conduct training using video platforms delivered through satellite. These are usually more expensive to deploy. Consequently, they become unsustainable due to costs.

This is another gap we expect that Google's Project Loon should fill. High-speed internet from this initiative can even lead to real-time training and supportive supervision. Ultimately, nations are better prepared for infectious diseases outbreaks when they have well-trained health workforce.

Beyond diagnoses, timely treatment could be the difference between living and dying in some of the remote communities that will benefit from Google's Project Loon. In addition, providing the right treatment may also be the remedy that would put a stop to an infectious disease that could spread beyond one location and become an epidemic. To achieve this, high-speed internet would make it possible for health workers in remote locations to be guided by specialists from any part of the world in providing timely treatment of infectious diseases.

Timely treatment can be the difference between living and dying in remote communities

For instance, the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak across west Africa began from an index case in a remote village in Guinea. Imagine if the child had been properly diagnosed and the right treatment instituted. This could have prevented the deaths of more than 11,300 people across Guinea, Nigeria, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Lastly, infection, prevention and control are hugely dependent on community awareness and behavior and when communities are educated on disease causation and their roles in it, there is a high chance that they would adapt positive behaviours.

Google's Project Loon could use mobile cinemas to stream health talks and dramas. For instance, about 5.6 million Kenyans stool in public (almost 11% of the population of Kenya). Poverty is one of many reasons for this. However, it is important for community health workers to keep educating communities about the dangers of open defecation, which include cholera and other infectious diseases and doing so through a mobile cinema may be effective. In Niger, UNICEF and other NGOs used open air mobile cinemas to educate desert communities on malaria prevention, HIV/AIDS prevention and water and sanitation.

To be sure, we are concerned about how Google would protect data generated. In the past, the tech firm has been accused of not adequately protecting data privacy. The government of Kenya and indeed governments of neighboring east African countries must ensure that data privacy is prioritised. African governments should see the need to fund and replicate this initiative across the continent.

As the balloons hover in Kenyan skies, we hope that Google's Project Loon leads to increased capacity to detect, prevent and respond to infectious disease outbreaks across east Africa.

Dr. Ifeanyi M. Nsofor is a Senior New Voices Fellow at the Aspen Institute and Senior Atlantic Fellow for Health Equity at George Washington University. He is the CEO of EpiAFRIC. You can follow Ifeanyi on Twitter @ekemma. Dara Ajala-Damisa is a microbiologist and Young African Leaders Initiative Fellow. She is programme manager at Nigeria Health Watch. You can follow Dara on Twitter @MissyDurrell.