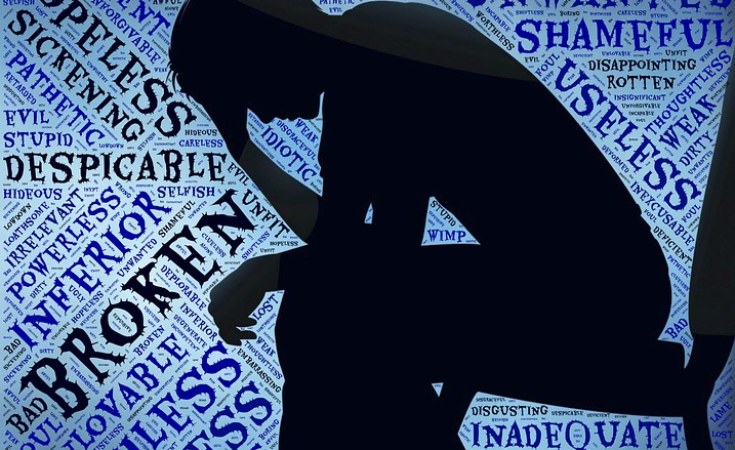

Johannesburg — As we move into the third year of the Covid-19 pandemic, we've also seen more openness about another global crisis. The rise in stress, anxiety, depression and other mental health illnesses has been dramatic during the lockdowns and social isolation of the pandemic. But in places where conflict, displacement and deaths have become widespread, the challenges of the past few years have added another layer onto the mental strain that people already face.

A panel of World Health Organization (WHO) experts on mental health in emergencies have looked at the impact of the novel coronavirus pandemic on people's mental well being, in the wake of a recent scientific report looking at the severe impact of Covid-19 on mental health.

"Three important findings from the report are that firstly, rates of mental illness like anxiety increased by 25% world wide and they are higher in some places where Covid-19 infections were higher and movements were restricted, women and young people were more affected than men. Secondly, people living with mental health conditions prior to Covid-19 were not in a higher risk of infection from Covid-19 but when they were infected they had a higher likelihood of having a severe illness from Covid-19 and even dying from Covid-19 complications, and lastly, the study found that mental health services had been disrupted worldwide," Brandon Gray, an expert in mental health in emergencies from the WHO headquarters says.

Gray says the pandemic shone a bright light on the fact that there had been decades of under investment in mental health services world wide. "We are seeing lack of investment and lack of priority from mental health care and services playing out during Covid-19 pandemic."

Follow us on WhatsApp | LinkedIn for the latest headlines

The report provides a comprehensive overview of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the prevalence of mental health symptoms and mental disorders. The report provides a comprehensive overview of current evidence about: the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours, the risk of infection, severe illness and death from Covid-19 for people living with mental disorders, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on mental health services, and the effectiveness of psychological interventions adapted to the Covid-19 pandemic to prevent or reduce mental health problems and/or maintain access to mental health services.

Gray says feelings of panic are normal in the abnormal settings people find themselves in, like conflict-affected areas. "Whether you are affected personally by an emergency or watching from afar, we are seeing how people are impacted and people involved in the response are also suffering, it is important to acknowledge that the fear, anxiety and the worry that people feel is normal. It is an expected reaction to extraordinary situations," he says.

Fahmy Hanna, a WHO expert in mental health, says: "Our study shows that 1 in 5 people after an emergency will suffer from a mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia or bipolar. While we are talking about the risk of getting a new mental disorder we should not forget the people with pre-existing mental health conditions even before the armed conflicts or humanitarian measures.

"Most of the humanitarian emergencies are coming on top of an existing public emergency which is Covid-19 and due to limited investment in mental health services before the pandemic by many countries, the mental health services are left exhausted, overwhelmed and in many countries insufficient to address the needs of mentally ill people."

Discrimination During Emergencies and WHO Response

There have been several report of discrimination against Africans when the Russia/Ukraine conflict started. Hanna says WHO provides support to all humanitarian emergencies equally and does not discriminate.

"When we receive requests to support in any country, first we coordinate with all actors globally and at country level to make sure that we are aware who is doing what, where and when regarding the mental health needs of the population. We also make sure that technical guidance becomes available in relevant local languages. While we coordinate with other actors we try to assist using specific technical tools on what the gaps are in mental health and psycho-social needs. Gaps refer to specific geographic locations, specific target groups and specific activities. From there we try to strengthen the local mental and psycho-social response using these tools," Hanna says.

Hanna, who just returned from Afghanistan as part of the WHO mission to support with mental health needs, says the country has 24 million people in need of mental health assistance, over 5 million people with common mental health conditions and around 1.2 million people with severe mental disorders. "Huge need, huge gap if we know that Afghanistan only has 100 specialized mental health professionals and most of them are centralized in the capital city, Kabul," he says.

Prolonged Post Covid-19 Complications

There has been reports of a high number of people living with prolonged post-Covid-19 complications across the world, this leaves a question about how this may impact on their mental health.

"It is difficult to know exactly which mental health symptoms are part of post Covid-19 conditions and the WHO team is still working to know more about that so it can clearly define what post-Covid-19 entails but we know common symptoms like depression and anxiety that people experience after adversity and it's also true that those are common experience after Covid-19 infection," Gray says.

Humanitarian Contexts with Extremely Low Resources

"South Sudan is a country almost the size of France with a population of roughly 12 million with only two specialized mental health professionals, only two psychiatrists serving the whole population. These two professionals have to deal with the daily needs of the population on top of the increasing need for services that are disrupted due to Covid-19 and on top of that the humanitarian needs because of the armed conflict in the country," Hanna says.

The East African country gained its long-fought independence from Sudan over ten years ago and has been facing a humanitarian crisis for years. One third of its population, roughly 4 million people, are displaced and unable to return to their homes. It has also faced floods, cycles of violence, and food insecurity among other tragedies. Despite a signed peace agreement under the leadership of President Salva Kiir in 2018 that was meant to end conflict in the country, challenges remain ahead of elections set for 2023.

Hanna highlights the need for the WHO to invest in systems for conflict preparedness and urged "governments, donors and humanitarian actors to consider mental health and psycho-social support an integral component of the packages of humanitarian support to countries".

Signs of Mental Health Needs and How to Recognise Them

Gray identifies a few examples including struggling to sleep as a clear indicator that one is experiencing stress. Routine disruption may lead to people struggling to function. Also struggling to focus on daily tasks and feelings of being overwhelmed and anxious all the time and constant feeling of sadness could also be the signs that one needs mental health support.

During emergency situations a lot of people want to get the latest news coming from the place affected by the conflict and in doing so people have too much exposure to information that can be harmful in that they can bring about feelings of anxiety. Selma Sevkli, a WHO expert in Mental Health who is in Poland tending to refugees of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, says it is important to be informed but also to limit the information intake by finding other activities to do to distract yourself.

Humanitarian workers may also experience stress while on a mission to give support to conflict affected people. Sevkli says what she is seeing in the Poland camps where she is currently based is that she and her colleagues are also experiencing a lot of distress. "It is important to be aware of our own self care before they become more chronic issues, to adjust them immediately through those routine, self care activities," she says.

"What we know is that during difficult times people cope better when they have social support. What also help people the most during emergencies is that when they have someone who is willing to listen and link them to practical support and showing care in the middle of the chaos in the middle of the humanitarian and emergency crisis for their emotional and social well being makes a huge difference," Hanna says.