Malians go to the polls Sunday to vote on the governing junta's constitution. The country's military rulers say the document has been drafted with the input of ordinary citizens, but observers fear it will concentrate power in the hands of the president.

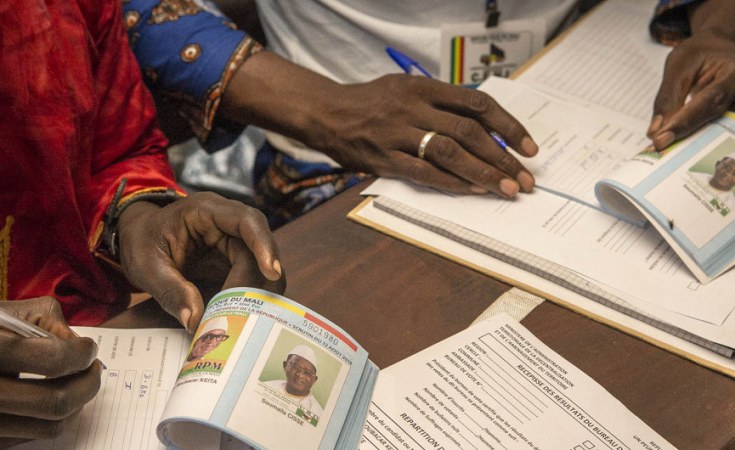

Polling stations opened at 8am GMT, with green ballots for the "yes" vote and red for "no". The results are expected within 72 hours of the closing of polling stations.

The junta announced the vote in early May.

Electoral process

The vote is the first organised by the military since it seized power in August 2020 in a coup that overthrew Mali's last elected president, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita.

It is a stepping stone towards a return to civilian rule with general elections scheduled for March 2024 under commitments made by the military.

However less than nine months before the deadline, the future role of the military is still not clear, nor is the role of junta leader Colonel Assimi Goita.

The military says this constitution could fix the existing one, which was enacted in 1992 and which is often blamed for Mali's problems.

This comes amid speculation that the country's strongman ruler will seek election.

For the moment, though, the Sahel country is gripped by a political, security and economic crisis. It is struggling to control jihadist violence, manage poverty and derelict infrastructure, and badly needs new schools.

Observers fear the vote could be disrupted.

Low participation?

For Sahel specialist Seidik Abba, author of a recent book on Mali, the main risk to the success of the elections is low participation.

He told RFI English that those who go out to vote will vote for the constitution.

"The population remains badly informed about the text," he said. "The campaign was too short so we're unlikely to see a strong participation.

Meanwhile political scientist Abdoul Sogodogo told the French news agency AFP that Malian people typically did not vote.

"Since 1992 turnout has rarely exceeded 30 percent."

Stronger presidential power

If approved, the new constitution would strengthen the position of the military, and the powers of the president.

The junta says it would also emphasise "sovereignty", and formalise the break with the former colonial power France, the military's principal mantra since coming to power.

Another point of dispute is that the new constitution would prevent Malians with another nationality from standing for president, says expert Seidik Abba.

"Mali is a country of emigration," he told RFI. "So millions of its citizens live abroad or have two nationalities."

The reform has drawn wide-ranging opposition from former rebels, imams and political opponents.

The demands from the Tuaregs from Northern Mali have not been included, and they have called on their supporters to reject or boycott the referendum.

Observers predict the "yes" vote is very likely to win.