The EU is "very concerned" that Niger's military leaders revoked an EU-backed law criminalizing migration. But residents of Niger's ancient crossroad town of Agadez are overjoyed about the move.

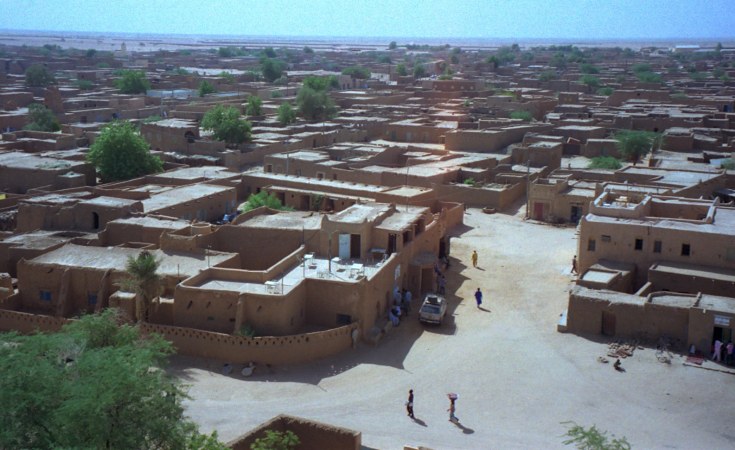

"We are overjoyed that this law has been repealed," said Bakray, a resident of Agadez, a historical trade hub on the fringes of the Sahara Desert in central Niger that has long been a crossroads connecting West Africa to the vast Sahel region, North Africa and the Middle East.

On the weekend, Niger's military junta signed an order revoking a law to curb the smuggling of migrants from West Africa heading north toward Europe. The law was enacted in 2015, under heavy pressure from the EU, at the height of the European migrant crisis.

Known as Law 2015-36, the legislation controversially made it illegal for migrants to travel from Agadez towards Niger's northern border. It also criminalized the work of the local "ferrymen" who transported these migrants towards Libya and Algeria.

Niger, the third poorest country in the world, received €1.2 billion ($1.32 billion) from the European Union between 2014 and 2020 in development aid, which many saw as coupled to the passage of Law 2015-36.

"It's not a Nigerien law," said Bakray. "It's not a law that really harmonizes with our mores and customs because it was imposed on us. It meant we couldn't welcome people with a full heart."

Hollow success

The number of migrants transiting through Niger and onto Europe dropped sharply over the years because of the law. But it attracted criticism from many quarters, from locals in the Agadez region to international migrant organizations.

The law disrupted many livelihoods dependent on the migrants in a region suffering from a drastic economic decline in the decade before its introduction. Migration provided "an economic buffer" found a study by the Centre for Africa-Europe relations (ECDMP), noting that one-third of respondents in Agadez had earned some form of income from the migration industry.

Another study found that in 2016, before Niger's government started enacting the law, as many as 333,000 people transited through Agadez, bringing in as much as $100 million, which helped stabilize the regional economy.

"When you travel around Agadez today, you can see the joy because it was an unpopular law," Salifou Manzo, a prominent civil society member in Agadez, told DW. "Effectively, it prohibited any activity linked to migration -- which ruined Agadez's economy and triggered many cases of drug abuse, theft and crimes.

"People are jubilant in Agadez because they know that this important income-generating activity is returning to the region."

Those convicted under the law will be considered for release, according to the military junta, something Manzo highlighted as an important move.

"Everyone who contravened the 2015-36 law, who were imprisoned, they're exonerated, they are free," he told DW.

Dangerous routes

The anti-smuggling law was also criticized for prioritizing border protection over the protection of people on the move. It forced migrants to take more dangerous routes.

Alarmphone Sahara, which provides a telephone hotline for migrants in distress, was one migrant organization that welcomed the repeal of Law 2015-36. It posted on X, formerly Twitter, that it was "good news."

Souley Oumarou, the coordinator of the Forum for Responsible Citizenship (FCR) in Agadez, also welcomed the end of the law as it hindered the rights of West Africans to move freely across the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) region.

"These rights to emigrate, to travel, to go to any destination they please ... have been restored through the repeal of this law," he told DW, "and for us, this is a good thing."

'Junta's reprisal'

As for the European Union, it warned that the law's repeal could lead to an influx of migrants into Europe.

"That will also probably mean more people coming to Libya for example and maybe trying to cross the Mediterranean to the EU," EU home affairs chief Ylva Johansson said on Tuesday. "I very much regret this decision and I am very concerned about the consequences."

Since the EU suspended aid to Niger after a military coup deposed President Mohamed Bazoum in July, tensions have been high between the European bloc and the ruling junta.

The repeal is seen as the junta's effort to regain local support and also to retaliate against the EU.

"The edict is part of a reprisal against this EU's decision," said Souley Oumarou, "with the aim of hurting Europe by allowing Africans to immigrate by sea to Europe.

"But for us, it's a restoration of violated rights," he said. "It gives the right to a certain number of operators who handle migrant transactions to exercise their profession and ... it restores the right for Africans to emigrate, to travel, to go to any destination they please."

Edited by: Louisa Schaefer