Uvira, Democratic Republic of the Congo — "The world's decision-makers know nothing about what is happening in my country."

I took the road from Kamanyola to Uvira in mid-December a few days after the signatures had dried in Washington.

On paper, peace had returned to my region in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Presidents had shaken hands, cameras had flashed, and Donald Trump had declared another war resolved.

Yet every kilometre of the road ahead told a different story. It carried the smell of gunpowder and death, and the signs of people who had fled in desperation. It showed how words spoken from above dissolve the moment they reach the ground.

Keep up with the latest headlines on WhatsApp | LinkedIn

A resident of one village near Uvira could not even describe the "horrifying" things he had witnessed as peace was supposedly being signed. "The world's decision-makers know nothing about what is happening in my country," he said.

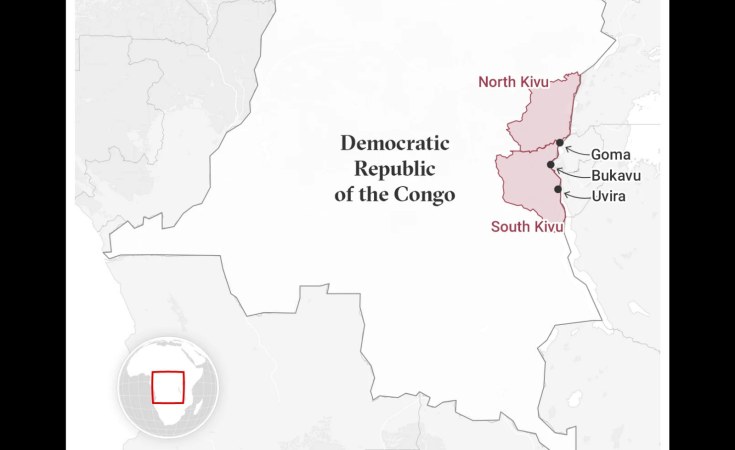

For more than four years, the M23 rebel group has waged an insurgency in eastern DRC, seizing vast stretches of North Kivu and South Kivu provinces, all with the help of thousands of troops and weapons from neighbouring Rwanda.

The insurgency has displaced millions, created one of the country's worst humanitarian crises in decades, and reopened the wounds of earlier Rwanda-backed rebellions in the 1990s and 2000s that killed millions more Congolese.

Yet towards the end of last year, there was a brief moment of hope. The presidents of Rwanda and DRC met in Washington and signed an agreement meant to halt the fighting.

Rwanda pledged to withdraw its troops supporting the M23, while Kinshasa promised to dismantle Rwandan rebels on Congolese soil. Trump bragged that "we are settling a war that's been going on for decades".

But just days later, the M23 advanced from Kamanyola, its forward position in South Kivu, to Uvira, one of the province's largest towns. The advance showed the world how little interest they have in peace - and in the civilian lives being torn apart.

I decided to travel the road from Kamanyola to Uvira to witness the gulf between the promises made in Washington and the reality on the ground.

It was a reality that left me cold.

After the handshakes

Kamanyola had fallen to the M23 in February last year, around the same time that the rebels had seized the two largest cities in the east: Goma, the capital of North Kivu, and Bukavu, the capital of South Kivu.

For months, people feared an onward assault on nearby Uvira, which had become an important stronghold for the Congolese army and pro-government militias (known as Wazalendo), and an entry point for Burundian troops supporting Kinshasa.

But the M23 chose its moment with audacity: on 9 December, five days after the signing ceremony in Washington.

The offensive - reportedly supported by Rwandan troops - shocked mediators and the few members of the international community that were paying attention to the conflict. Last month, under pressure from the US, the M23 withdrew from Uvira.

Still, by then so much damage had already been done: Tens of thousands of people had fled to neighbouring Burundi, countless lives had been lost, and whatever fragile trust people had in the Washington accord was shattered.

I arrived in Kamanyola on 12 December and found a city so different from the one I had visited just two years earlier. People were living under constant threat of M23 fighters and Congolese army shelling.

During my last visit, Kamanyola felt alive. Goat meat skewers filled the air with an appetising aroma, music blared from every intersection, and motorcycle taxis honked incessantly.

This time, the sounds of music had disappeared from the city's main thoroughfares. Some corners of the town were as quiet as cemeteries. The economy had slowed to a crawl, and many heads of households were unemployed.

Normally, a motorcycle ride from Kamanyola (which is still under M23 control) to Uvira cost between 30,000 and 50,000 Congolese francs (about 15 to 23 US dollars). After Uvira fell, the price nearly doubled.

The taxi driver who took me said the ride carried great risks. I realised this was not the usual story drivers tell to make a boring journey sound more thrilling. This was the reality of the war, even as statements of peace echoed from Washington.

The M23 had taken several towns along the road to Uvira, and the route was quiet; most people had fled. The doors of houses and shops were padlocked. The only sounds were rushing streams and the hum of our motorbike tyres on the dirt road.

Still, the signs of fighting were everywhere. Cartridges and shell fragments littered the ground. I passed the remains of deserted military positions, burned-out vehicles, and destroyed houses. Decomposing bodies of soldiers and civilians lay abandoned.

I spoke with a man standing in front of his house near Sange, about 35 kilometres from Uvira. Around his house, at least five bodies lay scattered - army soldiers, Wazalendo fighters, and civilians.

It was not lost on him that we were speaking about this offensive while peace had supposedly been agreed. "My heart bleeds," he said, "when I hear people boasting that they have ended the war in my country. The reality is so different."

"We are suffering, and the world is only superficially addressing the problems eating away at us," added a fuel vendor I met in Kiliba, 15 kilometres from Uvira. If there were a miracle that could bring peace, he would give everything to make it happen, he added.

Inside a captured city

As I approached Uvira, I saw from a distance Red Cross teams bringing in both civilians and soldiers who had died in the recent fighting around the city. I was told that journalists were not allowed to film the burials, so I did not go any closer.

Inside Uvira - a lakeside city with hundreds of thousands of residents - everything was subdued. People were mostly indoors, and only the most daring shopkeepers had reopened their stores.

Reporting openly on the streets was nearly impossible and people were hesitant to speak. "Les murs ont des oreilles," some said - "the walls have ears." Still, evidence of abuses committed by the M23 emerged in private conversations.

One woman told me she had witnessed a horrifying scene on 10 December: Two young boys from her neighbourhood, suspected of being Wazalendo fighters, were coldly gunned down by the M23.

A 21-year-old woman told me she was sexually assaulted by M23 soldiers. She said she stopped them from raping her by saying she had HIV in an advanced stage, but that did not prevent them from abusively groping her.

Another man recalled how local residents were forced to attend a demonstration to show support for the M23's arrival. He said they were threatened with beatings if they stayed at home or kept their shops closed instead of going to the rally.

Some residents, however, were positive about the M23. After months under the control of the Congolese army and abusive Wazalendo forces, they felt the new rulers were more disciplined and better at maintaining order.

Hearing gunfire had become commonplace in Uvira after the Congolese army's defeat in Bukavu. Hundreds of troops and Wazalendo forces poured into Uvira, carrying all kinds of weapons.

"If they remain disciplined and don't change their behaviour, let the M23 troops stay here," said a restaurant waiter. "We can sleep and wake up without expecting a single shot - unlike in previous days, when the Wazalendo were here."

After the M23 left Uvira in January, and the army and the Wazalendo returned, there was looting and targeting of the local Banyamulenge population - Congolese Tutsis of Rwandan descent who are often perceived as supporting the Tutsi-commanded M23.

Fearing for their lives, dozens of Banyamulenge families left the city alongside the M23, travelling north to Kamanyola, where they are now living in a camp that I visited last month.

"We fled because we were warned we would be killed for being Banyamulenge," said one woman who has lived all her life in Uvira. "We are not loved, we are attacked, and we are associated with the war."

The Congolese government characterised the Banyamulenge departure differently, saying they were "deported" from Uvira by the M23 and Rwandan army. It said violence against Tutsi communities is used as a "pretext" to justify the rebel insurgency.

The theatre of peace

That the offensive on Uvira happened after the peace agreement was signed tells us everything we need to know about the motivations of the belligerents - and about what the Washington negotiations were really about.

As our President Félix Tshisekedi travelled to the US, politicians in Kinshasa were saying the deal is not a surrender and that we will continue to fight Rwandan proxies. In other words, they signed an agreement while using bellicose rhetoric.

Everyone seemed to get something they wanted.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame no doubt intends to continue his long-standing policy of wreaking havoc in eastern DRC all while being cherished and lionised by Western countries. I do not believe that peace is his priority.

The M23, meanwhile, see withdrawing from Uvira as a gesture of good faith - but it is unlikely they will give up the vast territories they have seized. They openly state that negotiations between Rwanda and DRC do not concern them.

And as for Donald Trump, the agreement was a photo opportunity - a chance to show the world that a deal had been made. It was also a chance to further the long-running exploitation of Congolese resources by boosting American access over our minerals.

All this politics, posturing, and dishonesty is exhausting for those caught in the middle. One man I spoke to on my journey to Uvira told me that the bitterness in his heart is so profound, he fears he might end up poisoning someone.

"I was born into war, and I am growing up in war," the man said, adding that if it stretches on much longer, he may never know a country at peace. I hope - I pray - that peace will come, though this US accord may not be not the one to bring it.

Edited by Philip Kleinfeld.

Ladi Lutu, Pseudonym for a Congolese journalist based in the east of the country