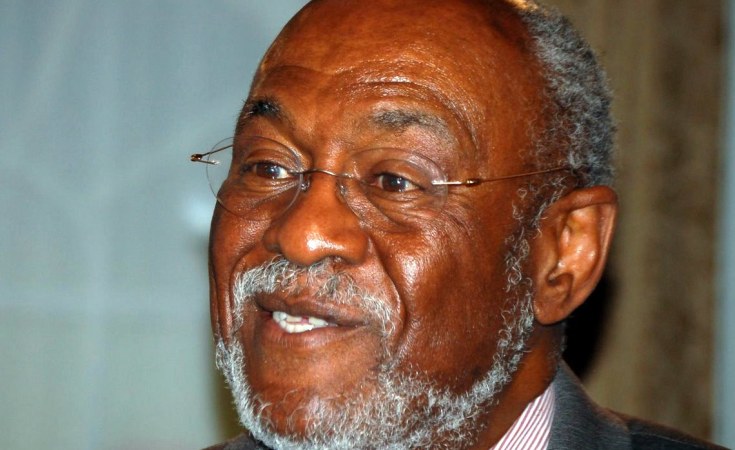

Washington, DC — Since taking office in May as the lead policymaker on Africa for the U.S. administration, Johnnie Carson has been on the go. As assistant secretary of state for Africa, he has made seven trips to the continent - most recently this month, when he visited four countries following the Africa Union (AU) summit in Addis Ababa. He has made frequent appearances in Washington and addressed audiences across the United States, and he is regularly called to the White House for high-level deliberations. In an interview this week, he provided an overview of U.S. policy priorities and listed the reasons he's bullish on Africa:

You frequently speak positively about Africa's prospects. Was that confirmed on your latest visit?

Yes, absolutely. I visited Ethiopia, Ghana, Benin, Togo and Nigeria, and there are powerful success stories just on that one trip.

In Ghana, President John Atta-Mills has demonstrated outstanding leadership in his first year and a half in office. He continues to put the interest of his country and his people before all else, and I think they're doing very well in Ghana. They're expected to be a major oil producer in the next two years, and I think they have learned that oil can be both a blessing and a curse. They know there are two ways to go - to take the Norwegian model or to take the Nigerian model. Oil has been a tremendous asset in helping Norway and its citizens become more affluent, more educated and more economically resourceful.

Nigerian oil has been a curse and has left the Niger Delta an environmental disaster, and it has left conflict in its wake. The Ghanaians realize this, and I think they will be good stewards of their oil and good stewards of their resources. I think they will use their resources on the basis of a strong democratic underpinning, and that's a good thing. That's a good news story.

Another good news story is Benin. We sometimes overlook small countries that are doing remarkably well. Benin, under its current democratic president, Yayi Boni, is using resources, as meager as they are, well and on behalf of the people. They've had an MCC (Millennium Challenge Corporation) compact - one of the early recipient countries - and they've used their MCC money extraordinarily well to work on agriculture, infrastructure and business projects. They're looking forward to successfully finishing their projects and making another request.

We forget that in the 1960s and 1970s there were more coup d'etats in Benin than almost every other place in Africa, probably with the exception of Nigeria. But over the last two decades, we've seen successive democratic elections there. We've seen President [Mathieu] Kérékou win. We've seen President [Nicéphore] Soglo win. We've seen a reversal with Kérékou coming back. That's a compliment to the people of Benin.

We hope that Togo, which sits between two democratic states [Benin and Ghana], will also have good elections in the beginning of March. Togo is at a crossroads, and if these forthcoming presidential elections can be free and fair, Togo could begin its march towards a more representative democracy that spends a lot more time on building the country's economy and restoring critical infrastructure. I think that's a possibility.

What about other places on the continent?

We continue to see good progress in South Africa under President Jacob Zuma. His personal family issues notwithstanding, he has outperformed any of the expectations when he came into office.

A number of other African states should be applauded for their strong commitment to democratic values and principles. We see continued good progress in Botswana under the leadership of Ian Khama. We see a democracy continuing to move forward in Namibia. We see democracy move forward in Malawi, where President [Bingu wa] Mutharika has just assumed the chairmanship of the AU. And I think he will be substantially better than his predecessor at the AU [Libya's Muammar Qaddafi].

In Liberia, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf continues to do an excellent job, focused on delivering services, attracting foreign investment, improving infrastructure from ports to electricity to roads, and trying to find as much foreign assistance as she can to help her country. Liberia is fortunate to have a leader who is so single-mindedly focused on making things better for the people.

We see the democratic progress in Zambia and in Tanzania. We see good things in Mali, Cape Verde and Mauritius. There are a number of African countries that should be applauded for their progress.

What can and should the United States contribute to encourage political and economic progress in Africa?

Political goodwill, positive encouragement, constant support for civil society and the principles of democracy. Constant dialogue with those that are part of the political elite. Support for civil society and an independent press. And a willingness to put our resources and money on the table to help reform - institutional reform that will strengthen democracy. We should come to the table with resources to help.

I would also be quick to add that if we see people not doing the right things, people who are undermining the values of democracy, people who are corrupt, we should not only step back, but we should criticize in a principled fashion.

We should be engaged and we should encourage others to be engaged as well. That's absolutely critical.

How do you assess democratic prospects in Nigeria?

The Nigerian political elite made a strategic choice, and they made it in favor of democracy. They made it in favor of trying to work out a solution acceptable to the north and south, east and west, designed to create stability, constitutionalism and rule of law, including how a succession to the presidency is handled under an unexpected and adverse situation.

We hope that this difficult period they're going through now not only will test their young democratic institutions but will strengthen them and harden them like a piece of steel as they go forward.

I'm fond of saying that Nigeria and South Africa are the two most important countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Nigeria is too significant to ignore. With 150 million people, it has the second largest Muslim population in Africa after Egypt and the seventh largest Muslim population in the world. Producing 12 percent of U.S. petroleum needs, it is the largest supplier of our sweet crude. A stabilizer in West Africa, it is - despite its weakened economy - the dominant economic powerhouse in the region. A major contributor to international peace and stability beyond its borders, it is one of the top 10 providers of peacekeeping troops around the world.

The country is just too big and important for us to sit on the sidelines and ignore - both its potential and promise but also its prospects for peril and disaster if things go wrong. We need to help encourage the forces of democracy and economic reform and good governance and economic change.

Many Nigerians have criticized the decision by the American government in early January, following the failed effort by a young Nigerian to blow up an airplane bound for Detroit, to add Nigeria to the 'countries of interest' whose residents face enhanced scrutiny entering the United States.

Many leaders and many informed and educated Nigerians were both surprised and upset when Nigeria was put on the watch-list. They felt that collective punishment was being visited on Nigerians as a result of one individual's actions. I said that as painful as this is and as sorry as we are to see it happen, let us work together to improve Nigeria's security awareness so that it can be taken off this list as quickly as possible.

We don't want to stigmatize any Nigerian, and 99.9 percent of all Nigerians are honest and law-abiding citizens. They have no desire to be affiliated with any kind of extremist groups [and] would never engage in any kind of terrorist activity. This is true of the United States, too. But it does happen, and just as it can happen with one or two Americans, it can happen with one or two Nigerians. The watch-list will ensure that all of us are safer.

We in the United States have adopted security procedures because we recognize that this is something that applies to all of us. We have pretty rigorous procedures here. I told Nigerians that if they were flying from Chicago to Charlotte, like any other traveler, they would have to take off their shoes and their belts and not have any liquid in their possession that's over two ounces. They could not have any pocketknife or sharp item, and they might, if they're randomly selected, have to go through a full-body scan. We do that to Americans, although 99.9 percent of them will never be associated with any kind of terrorist organization. Even with them on the list, we're not asking for them to do anything more than what we're doing ourselves. We've tried to put it into perspective for them.

I am encouraging Nigeria to do four things, very specifically, that would help to ensure a review and hopefully favorable treatment and perhaps a de-listing. And I emphasized that the de-listing issue is in the hands of Homeland Security not the State Department.

We encourage the Nigerians to sign an agreement that allows U.S. sky marshals to fly on any planes that are originating in Nigeria going into the United States. This helps to provide safety and security for all passengers. Secondly, we encourage them to improve port security, and we said we will help them do that, just as we also said we would help them to train their own sky marshals, to be substitutes for the sky marshals that we want to put on.

Thirdly, we said it was important for them to adopt new criminal procedures that focus on terrorism, just as we have laws that focus on felonies and assaults and muggings and murders. And finally we said that, as painful as it is, it's important for Nigerians to recognize that they could have a problem. It may be a new or emerging problem, and it may be a small problem, but ignoring that there could be individuals of Nigerian origin who are terrorists is to take a head-in-the-sand approach.

Turning to Niger, what can you say about U.S. policy in the aftermath of the military takeover on February 18 and the ouster of Mamadou Tandja?

All coups are bad, whether they are the extra-legal sort that President Tandja carried out in December or a military coup of the type carried out last week by military officers. They both are designed to promote the interests of small segments of the population for their own interests.

The United States was firmly against what President Tandja did in December by extending his term of office. He rejected the constitution. He rejected the highest court in the land, and he rejected the views of his legislature in extending his term of office. He held a sham referendum, which had a very, very low voter turnout, and extended his [stay in] office illegally. When we saw him moving against the legislature, the courts and the constitution back in June or July, our ambassador in Niger said very clearly that if he continued along the path he was going on, the United States would take action. And we did. By the time December had come along, we had cut our Agoa (African Growth and Opportunity Act) program - eliminated it. We had eliminated our MCC program. We had eliminated all of our foreign assistance except emergency humanitarian assistance. We had stopped all of our military activities, including asking Nigerien students who were in the United States to leave and go home.

We consulted with Ecowas (Economic Community of West African States) and with other key partners. We let it be known that we would not accept to do business under normal circumstances if President Tandja overthrew the democratic order in order to serve his own interests. We didn't do this with a lot of fanfare. So last week, when people asked me if we were going to cut off our assistance to the government, I said we'd already done it.

If the individuals responsible for the intervention by the military really believe in democracy, they should set a swift timetable for an immediate return to democratic rule. And they should follow the AU norms in that none of those involved in that coup d'etat run for office. Those who tear down should not be allowed to benefit from the rebuilding.

How do you view the prospects for democracy in Guinea (Conakry) and how do you assess the leadership role played by Ecowas in both Niger and Guinea?

Ecowas has been very active. The Ecowas special envoy for Niger, former General (and former Nigerian head-of-state) Abdulsalami Abubakar, has played a very useful role there.

The outgoing head of Ecowas, Dr. Mohammed Ibn Chambas, has done an outstanding job. He's been one of the finest international civil servants on the continent over the last decade, and he will be greatly missed. (Chambas stepped down after nine years at Ecowas to become secretary general of the Brussels-based Secretariat of the 79-member group of African Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) nations on March 1).

But another leader stepped up to the plate and delivered on Guinea, and that's President Blaise Compaoré (Burkina Faso). He has played a positive role in encouraging a swift return to civilian government in Conakry. He has taken in the former military ruler, Dadis Camara, who still needs medical attention for the severe wounds he suffered [in an assassination attempt in December]. If the situation in Guinea-Conakry had gotten further out of control, if Dadis Camara had come back, if the military had attempted to retain its power, then instability in Guinea would have had a spillover effect into Liberia and other regional countries.

I'm optimistic. A civilian-led transitional government is in power. The military has moved off to the side. None of the individuals who were involved in the coup or in the violent events that occurred [during a pro-democracy demonstration] at the end of September in the stadium will be allowed to run for office, and there's still a commitment to hold elections within the six months agreed to by all the parties.

Everyone seems to be supportive of the Ouagadougou accords that were worked out by President Compaoré, and I think it's important that Ecowas and the international community continue to play a monitoring role in that country. I would like to see a small Ecowas civilian and military observer force on the ground. It would provide additional diplomatic eyes and ears for the Ecowas community. It provides confidence and reassurance to the civilian population who has been betrayed before. And it provides a watchdog to let the military know that their actions will be seen by the international community.

Do you think it will happen?

There's a possibility that it may, closer to the election. It would be a useful vehicle, and it also would be a nice precedent for Ecowas to have observer missions - not a peacekeeping force, but a small civilian and unarmed military observer mission to help ensure that security and political situations are handled in the appropriate fashion.

At this point, I remain positive about what I see in Guinea and, again, applaud President Compaoré for his efforts. There is also a nod to be given to Morocco, particularly Moroccan Foreign Minister Fassi Fihri, because he was very helpful in the early stages as well.

There's a new effort this week by Ecowas to mediate in Cote d'Ivoire as well, following President Gbagbo's postponement again of the election there.

Yes, we hope that President Compaoré can bring the same kind of sustained commitment in helping to resolve the same kind of problem in the Ivory Coast.

Before we use up our allotted time, let me ask you to outline your top priorities in the Horn of Africa.

The most important issue in the Greater Horn of Africa has to be Sudan. Let me just say very clearly that we are looking for the full implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the north and south. And we fully expect there be a referendum in January 2011 that will allow the people of South Sudan the right to remain a part of South Sudan or to vote for independence. Making sure that the CPA is implemented, the referendum is held and that people are allowed to make a choice is a key priority in the area.

The second one is to see an end to the humanitarian and the political crisis in Darfur. We acknowledge some significant and positive progress in the improvement in relations between Chad and Sudan, and hope that that will contribute to both stability and a return to a normal situation in Darfur. That is key.

Secondly, in terms of major priorities, is Somalia. We continue to support the Djibouti Process, the TFG (Transitional Federal Government), and Sheikh Sharif's government. We think it is important to marshal as much support as we can behind this process to help strengthen it, and to give Somalia an opportunity to come out from a political nightmare and a security nightmare that has gone on for two decades. We support the Amisom (African Union Mission in Somalia) effort and we hope that more countries would support it.

Thirdly and equally, we want to see Kenya move forward with the completion of a new constitution, so that the next time it has presidential elections they would not result in the kind of violence that occurred after the December 2007 elections. Where January and February 2008 nearly ripped Kenya in half east to west, the new constitution and a new political framework endorsed by both the ODM (Orange Democratic Movement) and the PNU (Party of National Unity) can set Kenya on a new path.

A fourth agenda item is to have a more balanced, broad-based and comprehensive relationship with Ethiopia. Our relationship with Ethiopia on the security-sector front has been excellent. We want to ensure that we can have a dialogue with Ethiopia on critical issues concerning economic development, democracy and human rights. We want all of those areas to be as significant and as important and as good as that security relationship is. It's not a zero-sum game. The pie is large enough to grow, but we want to see things happen there that are much more positive, especially on the economic front.

They've had seven percent economic growth, but Ethiopia also has one of the fastest growing populations in Africa. With the population increasing by 1.5 to two million people a year, it will soon - probably in the next five years - overtake Egypt as the second most populous country in Africa after Nigeria, with a quite significant increase in its Muslim population as well. It's important that we have a broad, comprehensive and good relationship with Ethiopia, and we need to be expanding the dialogue.

With the deterioration of political and humanitarian conditions in Somalia, is the administration engaged in seeking a political solution or is the policy emphasis now almost exclusively on security?

I think there is room for a political solution. We continue to encourage the Transitional Federal Government and President Sheikh Sharif to reach out to clans and sub-clans, to reach out to moderate Islamic organizations and groups, to reach out to the west and to the south, to find alliances with those who seek to improve both the security and the effectiveness of the state. And we encourage the government to deliver services, however small, to areas that are inside of their control - to act like a government and deliver services like a government - not just security, but services.

And is the United States helping with that?

Yes the U.S. is helping. We have signed a few grants and are looking to help provide resources that they can use - money to deliver services and maybe medicines in clinics and books in schools. Government services that give them credibility. The TFG are a counter-weight to the hard-line extremism of al-Shabaab. And many Somalis, if they had a choice between the TFG and its desire to improve the lives and welfare of people, and Shabaab, who bring a violent form of Islamic radicalism, they would in fact choose the TFG.

Sheikh Sharif has been in power for less than 18 months. He came in as a little-known figure. His strongest asset - that he was not a warlord - was also [his] greatest weakness. He did not command an army. He did not have a band of people around him with guns and arms. He was not an intimidator, and he was not a criminal or a thug. In a place like Somalia, if you're not armed, you're not likely to survive very long. I think he's done a remarkable job of surviving. We want him to succeed and not just to survive.

How would you describe relations with Eritrea and what can you say about Eritrea's role in Somalia?

The administration started off trying to establish a positive relationship with Eritrea. I sought to go out there. It's widely known that the Secretary sought to contact Isais Afwerki (the president). Our attempts were spurned.

Eritrea can play a positive role in the Horn of Africa. It has not been playing that role in the last several years. We encourage Eritrea to take stock of what's going on inside and outside its country and to play a positive role. If it plays that positive role, there would be a positive response, certainly from the U.S., as well as from the international community and from its neighbors. The great condemnation of Eritrea hasn't come from Washington. It's come from Eritrea's IGAD partners around the region. They've been most affected by the destabilizing politics that Eritrea has spawned in the area.

NOTE: Eritrea withdrew from IGAD (the Intergovernmental Authority on Development) in 2007, leaving five member-nations - Djibouti, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan and Uganda.

Finally, the African Union has given the 'de facto' government in Madagascar headed by Andry Rajoelina until March 16 to implement the power-sharing arrangement that all parties have accepted. Does the United States support that action?

We've worked very closely with the AU and Jean Ping (president of the AU Commission). We share the same goals of the return to democracy in Madagascar. We believe very strongly that those who disrupt or violate authority shouldn't choose the terms under which new democracy can be returned. We are going to continue playing a constructive role. Our position is not totally similar to the position of the AU, but our objectives are the same, and we will continue to work closely with them.