How is international criminal justice meted out?

I - INTRODUCTION

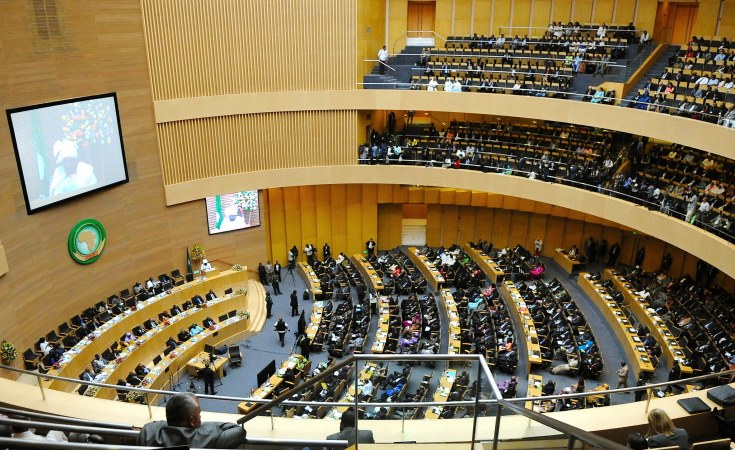

i) African Participation

On July 17, 1998, many states adopted the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (the Rome Statute)[1] and it entered into force on July 1, 2002, after attaining 60 ratifications.

Today, 121 states are parties to the Rome Statute - including 33 of Africa's 54 states[2]. Of these, Senegal was the first state in Africa and the whole world to ratify the Rome Statute on February 2, 1999, while Cape Verde is the most recent African state which ratified the Rome Statute on October 10, 2011. African states were at the forefront of the establishment of the ICC. Indeed, on the day the Rome Statute was opened for signature on July 17, 1998, a number of African states signed it - Liberia, Niger, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe[3].

On July 1, 2012, the world celebrated the 10th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute. Despite the suggestion that it owes its origins to a 'statute', the International Criminal Court (ICC) is actually a treaty under international law - an international agreement concluded between states in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments[4]. By ratifying the Rome Statute, 33 African states have accepted the jurisdiction of the ICC and full international obligations arising from the Rome Statute. These obligations include cooperating with the ICC in the investigation and prosecution of persons responsible for crimes within the jurisdiction of the ICC[5].

ii) Crimes covered

The ICC is primarily tasked with the prosecution of persons responsible for the most serious crimes of concern to the international community. According to Articles 5, 6, 7 and 8 of the Rome Statute, these crimes include genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity. The definition of the crime of aggression was agreed at the Kampala Review Conference in June 2010, and will also be included once 30 states have ratified it. By punishing the perpetrators of such crimes, the ICC contributes to their prevention and the elimination of impunity.

iii) Jurisdiction and national sovereignty - the principle of complementarity

It is primarily the responsibility of every state to exercise its own criminal jurisdiction over persons responsible for international crimes. Hence, the ICC should operate as a complementary institution.

According to Articles 1 and 17 of the Rome Statue, the ICC can only investigate and prosecute the perpetrators of international crimes if national criminal jurisdictions have failed or are unable to prosecute the perpetrators.

Under the principle of complementarity, national authorities have the first opportunity to prosecute. And in principle, the Rome Statute expressly gives preference to national criminal jurisdictions over the ICC. Thus, it is only when states have failed to take advantage of the complementarity principle that the ICC can deny them of this opportunity.

iv) The ICC's mandate

Normally, the ICC can have competence over a situation from a given state by one of four ways, as provided for under Articles 12(3), 13, 14 and 15 of the Rome Statute:

The first instance is when a situation is referred to the Prosecutor of the ICC by the state itself. The ICC is empowered to take action if the crime was committed on the territory of that state, or if the perpetrator is a national of that state and the crime was committed after the entry into force of the Rome Statute in the particular state.

Second, the ICC can have power to prosecute if the situation has been referred to it by the United Nations Security Council, which acts under the powers conferred upon it in Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations. This means that the Security Council must first determine that the situation constitutes a threat to international peace and security.

The third method is when the Prosecutor of the ICC has initiated an investigation proprio motu (on his own) based on information received on the crimes within the jurisdiction of the ICC.

Finally, the ICC can have power to prosecute perpetrators if a state which has not ratified the Rome Statute files a declaration to the Registrar of the ICC accepting the jurisdiction of the ICC over crimes and that state undertakes to cooperate with the ICC in the investigation and prosecution of such crimes committed within its territory.

II - CASES BEFORE THE ICC ARE FROM AFRICA

There are seven situations from African states currently before the ICC (Kenya, DRC, Central African Republic, Uganda, Mali, Ivory Coast and Libya).

Out of these, situations in Mali, DRC, Uganda and Central African Republic resulted from state referrals.

Ivory Coast is a situation by way of a declaration under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute.

The Kenyan situation is by proprio motu powers of the Prosecutor of the ICC.

Libya and Darfur, Sudan are the only two situations referred to the Prosecutor of the ICC through resolutions of the Security Council (Resolutions 1970(2010) and 1593(2005)).

All situations have resulted in 17 cases before the ICC[6]. However, some cases have been terminated upon death of the suspects.

III - ARE THE ICC AND THE SECURITY COUNCIL BIASED AGAINST AFRICA?

It should be noted that all cases currently before the ICC are from African states. It is because of this fact that some people, including African state officials, have argued that the ICC has targeted Africans. Particularly interesting here is the interplay between the outwardly neutral field of law and the political decisions that are a symptom of ICC involvement.

i) The power to defer

Under Article 16 of the Rome Statute, the ICC has the power to defer cases for a year at the behest of the Security Council.

Despite numerous attempts by the African Union (AU) to delay cases concerning Libyan, Kenyan and Sudanese state officials, the Security Council ignored requests to defer the ICC cases. The AU contended that they were important players in the peace processes of these states and as a result adopted a series of resolutions stating that it shall not cooperate with the ICC in the arrest of the President of Sudan, Kenyan state officials and Libyan officials.

Notable here are fruitless efforts by the AU to challenge the ICC in the warrant issued against the Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir. There came the 'Sirte Resolution' in July 2009 calling on African Union Member States to withhold cooperation from the ICC in the arrest and surrender of Sudanese President. This was to be followed by other decisions with similar effect, raised at the 16th African Union Summit in January 2011. With AU backing, President Omar al-Bashir has visited a number of AU Member States - Kenya, Malawi, Egypt, Libya, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Chad.

Reacting to the visits to these states, the Prosecutor of the ICC reported the matter to the Security Council against these African states. The AU has defended these states that have hosted the Sudanese president by contending that they have not breached any of their international obligations, stating merely that they have been enforcing AU decisions not to cooperate with the ICC.

ii) Similar crimes, different actions

The AU argument is that the ICC has been selective in its method of investigating and prosecuting perpetrators of serious international crimes in that it has so far failed to accept the glaring truth that similar crimes have been committed in other parts of the world with impunity.

Critics point to the crimes committed in Iraq since 2003, a situation instigated and planned by the political leaders and military commanders of the United States of America, the United Kingdom and their allies. Reports of the investigations by John Dugard and Justice Richard Goldstone similarly highlight international crimes by members of the armed forces of Israel against Palestinians. War crimes committed in Georgia following acts of aggression by Russian troops in 2008 could also fall within the ICC's remit.

The continuing situation in Syria compounds the compelling truth that crimes similar to those investigated in Libya (since February 2011), Darfur in Sudan (since 2003) and Kenya (December 2007- 2008) are being committed without international action. The Security Council has failed to adopt a resolution referring the matter to the Prosecutor of the ICC for investigation and prosecution of those responsible for crimes against humanity and war crimes. Equally, the Prosecutor of the ICC has failed to invoke his powers to initiate investigation and prosecute perpetrators of the crimes that can fall within the jurisdiction of the ICC.

It is easy to see that not all acts that best fit the definition of international crimes are being investigated. This weakness in both the Prosecutor of the ICC and the Security Council has led some in Africa to argue that the ICC has adopted an active role in Africa while remaining passive in the situations in other parts of the world.

iii) Problems with jurisdiction and resources

Those who have defended the ICC build their argument upon the fact that there are limited resources available to the ICC and it is quite simply not yet possible to investigate crimes in so many different countries simultaneously. In some countries, rather questionably, the findings of NGOs have been used to underpin proper legal investigations.

Further, one needs to fully appreciate the legal requirements specified in the Rome Statute for the ICC to have power over crimes committed in states. Article 12(a) and (b) of the Rome Statute expressly require that the ICC can have jurisdiction over crimes if such crimes are committed on the territory of a state party to the Rome Statute, or if the crimes were committed by the nationals of a state party to the Rome Statute. Unless the Security Council decides to refer situations in Iraq, Syria and the predicament of Palestinians to the Prosecutor of the ICC, the ICC cannot have jurisdiction over such situations. Such states are not parties to the Rome Statute, so the ICC is legally curtailed from exercising its powers over anyone who commits crimes in such states. In such circumstances, the Security Council must adopt a resolution referring such situations to the ICC.

iv) Overlapping obligations

It is important to realise that the pursuit of international criminal justice is not new. Customary international law has long imposed obligations on states to either prosecute perpetrators of international crimes or else to extradite these persons to other states prepared and capable of prosecuting them. This is known as an erga omnes obligation, which in Latin means "towards all", and is owed towards the whole international community. Failure to act leads to state responsibility in international law. Hence, African states may be committing an international wrongful act by failing to prosecute the perpetrators of international crimes or at least surrendering them to the other states (and by extension the ICC) to prosecute them. International criminal justice has long been established and pursuing this through the ICC has provoked mixed reactions.

By participating in the decisions of the AU summit, some of African states, especially those within the Great Lakes Region, are in clear violation of their obligations not only from the Rome Statute, but also under the provisions of the Protocol for the Prohibition and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Crimes against Humanity, War Crimes and All Forms of Discrimination, adopted by the International Conference of the Great Lakes Region in 2006. This Protocol calls upon member states to cooperate with the ICC in the investigation and prosecution of international crimes, and to domesticate the Rome Statute to allow cooperation with the ICC. Importantly, it rejects immunity of state officials (article 12).

Possibly, the obligation to punish crimes such as genocide is imposed by the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide 1948, where states accepted that genocide is an international crime punishable either by national competent courts or international tribunals. Here it is argued that the ICC is a proper international penal tribunal. So, failure to cooperate with the ICC is a breach of international law obligations, not only under the Rome Statute but also the Genocide Convention.

iv) The Security Council Veto

The involvement of the Security Council demonstrates an inherent problem with the Rome Statute - it brings law onto the shores of politics. The possibility of a veto power by the permanent members of the Security Council precludes situations that are not in their partisan interests.

It is unimaginable that the USA and UK would vote for any resolution which might call for an investigation into the situation in Iraq when they provided the stimulus for such violations. Similarly, the situation harming Palestinians is likely to be vetoed within the Security Council because USA, UK and France are likely to side with Israel and disregard the crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression committed by Israeli political leaders and members of the armed forces. A resolution could lead to the application of Chapter VII powers, which could allow the Security Council to authorise the Prosecutor of the ICC to begin an investigation into the situation in Syria. This was done in Darfur and Libya whereby individuals, including Sudanese and Libyan state officials and military commanders were indicted by the Prosecutor of the ICC for crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide. It is quite clear that Russia and China would use their veto to prevent this in the Syrian situation.

v) Varying levels of implementation - The al-Bashir example

The veto exposes an inherent weakness of international criminal justice. It would seem the law applies most effectively to the weaker states, leaving the political leaders from powerful states free from the reach of justice - something which goes against its very raison d'etre.

So how has implementation of the Rome Statue varied and what are its implications? The example of President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan will be used to gauge responses. And in this context, former Malawian President Bingu wa Mutharika remarked that the ICC seems to disregard the immunity and sovereignty of African states and their officials.

African Union sentiments towards the ICC are sharply opposed by a section of certain African states through law and practice. Although the AU purportedly speaks as one voice, one must be aware that some African states - particularly South Africa, Botswana, Malawi, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Niger, Kenya, DRC, Uganda, and Central African Republic - provide evidence that they are not totally in agreement with what is adopted by the AU Assembly of States.

Mutharika's successor, Joyce Banda, recently made it clear that if President Omar al-Bashir stepped on the territory of Malawi for the AU Summit on July 12, 2012, he would be arrested. This explains why the AU had to move its summit from Malawi to Ethiopia in July 2012. The act of moving the summit from being held in Malawi was condemned by Malawi and Botswana. Botswana issued a communiqué on June 12, 2012 challenging the legality of changing the action by alleging that it denied Malawi an opportunity to fulfil its obligations under the Rome Statute[7]. Botswana has also made it clear it would arrest the Sudanese President if he visits the country.

It argues that it has an express obligation under the Rome Statute to cooperate with the ICC including by arresting and surrendering suspects to the ICC. South Africa[8], Kenya,[9] Uganda,[10] Burkina Faso, Niger, Senegal and Mauritius have incorporated the Rome Statute into domestic law. The Kenyan High Court at Nairobi issued a decision in which it compelled state authorities to arrest the Sudanese President should he visit Kenya. The decision followed the failure by Kenya to arrest him in 2010.

vi) Speaking as one

So what are the broader implications of these mixed reactions to the al-Bashir case? Regional divisions amongst member states show that there is no common African agenda against the ICC. This is embodied by the efforts the AU has made to adopt a treaty establishing a criminal division of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights. As this process is on-going, the East African Community (EAC) has also embarked on creating a criminal jurisdiction within the East African Court of Justice. Why would the East African Community establish a criminal jurisdiction within its Court of Justice if the AU has gone into advanced stages of adopting a treaty for similar purposes?

And against this, a substantial number of African states have, by their own will, referred situations to the Prosecutor of the ICC. A recent example is Mali,[11] which despite its Penal Code and the Rome Statute allowing it to exercise jurisdiction, through a two page letter of July 13, 2012, signed by Malik Coulibaly, Minister of Justice, referred the situation in northern Mali to the Prosecutor of the ICC for investigation and possible prosecution[12]. This is similar to referrals by Uganda, DRC, and Central African Republic. Likewise, in May 2011 the President of Ivory Coast referred the situation in that country to the Prosecutor of the ICC by way of a declaration recognising the jurisdiction of the ICC for crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in Ivory Coast.

IV - CONCLUSION

All cases pending before the ICC, including those which have been decided by the Trial Chambers of the ICC (that of Thomas Lubanga Dyilo and Callixte Mbarushimana) have followed proper procedures stipulated under the Rome Statute. Rules of proper procedure cover the rights of suspects and accused persons before and see control by the Pre-Trial Chamber over the Prosecutor at all stages of investigation, and a committal of proceedings to the Trial Chamber for full trial. Notably the case of Callixte Mbarushimana was concluded for lack of sufficient evidence and a failure by the Prosecutor to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Mbarushimana was responsible for crimes committed in DRC in 2009.

The decisions taken by the AU not to cooperate with the ICC in its investigation and prosecution of persons responsible for crimes committed in Africa do not take into consideration that the AU itself as an inter-governmental organisation has an international obligation to cooperate with the ICC based on Article 87(6) of the Rome Statute. This can arguably lead to a strong case before the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights which has jurisdiction to enforce international law, including provisions of international treaties ratified by African states parties to the Rome Statute and various African human rights treaties.

Further, decisions by the AU not to cooperate with the ICC amount to blatant violations of the principles contained in the Constitutive Act of the African Union, 2000 (articles 4(m) and 4(o)) which reject impunity for crimes. Similarly, African states participating in the decisions of the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government, particularly those states parties to the Rome Statute are breaching their obligations under the Rome Statute (articles 86-93 under Part IX of the Rome Statute) by failing to cooperate with the ICC something which entitles the ICC to report them to the Security Council for actions.

It is a fact that the ICC has only been able to prosecute individuals from African states. It is equally true that the Prosecutor of the ICC has not used the powers conferred upon him/her to initiate investigations into situations other than those in Africa. The fact that the Security Council has not empowered the Prosecutor of the ICC to proceed against certain key political and military leaders in powerful states in the world for their crimes should not be interpreted to mean that the Prosecutor does not have the potential to do so.

If he or she were to apply customary international law - one of the sources of law - before the ICC, then it would be possible to indict even leaders from powerful states who have committed serious crimes similar to those committed by African individuals. Based on customary international law, the Prosecutor can indict individuals on other legal principles such as - that international crimes are imprescriptible.

For more information about the course please read our introductory blog post.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

1. What obligations are placed on states after ratifying the Rome Statute? To what extent are these obligations met?

2. Over what crimes does the ICC have jurisdiction? How effective is this jurisdiction?

3. How plausible is the argument that the ICC and the Security Council are biased against Africa?

4. What is the significance of erga omnes obligations to the jurisdiction and effectiveness of the ICC?

5. What is the relationship between African legal instruments and the ICC?

FACTS:

1) The ICC budget for 2012 was €108,800,000 of which Japan, Germany, Britain, France and Italy together contributed more than half.

2) The International Criminal Court has been ratified by 121 countries - but not by the United States

3) The court has no retrospective jurisdiction - it can only deal with crimes committed after July 1, 2002, when the 1998 Rome Statue came into force.

4) The Court's first verdict, in March 2012, was against Thomas Lubanga, the leader of a militia in Democratic Republic of Congo. He was convicted of war crimes relating to the use of children in the country's conflict and sentenced in July to 14 years of imprisonment.

5) Among those wanted by the ICC are the leaders of Uganda's rebel movement, the Lord's Resistance Army, which is active in northern Uganda, north-eastern DR Congo and South Sudan. Its leader, Joseph Kony, is charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes, including the use of child soldiers.

6) The US threatened to pull out of the UN force in Bosnia unless the ICC gave them immunity from prosecution. The UN Security Council voted on July 12, 2002, to give US troops a 12-month exemption from prosecution - renewed annually. This agreement was revoked in 2004, two months after pictures of US troops abusing Iraqi prisoners shocked the world.

[1] Adopted on 17 July 1998 by the United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 2187, p. 3.

[2] See, http://www2.icc-cpi.int/Menus/ASP/states+parties/African+States/ (accessed on 26 July 2012). The African states parties to the Rome Statute are Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tunisia, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania and Zambia

[3] http://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XVIII-10&chapter=18&lang=en (accessed on 26 July 2012).

[4] Article 2(1) (a), Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969.

[5] Articles 86 - 93, Part IX of the Rome Statute.

[6] http://www.icc-cpi.int/Menus/ICC/Situations+and+Cases/Situations/ (accessed on 26 July 2012).

[7] Press Release, 'The Hosting of the 19th Ordinary Session of the AU Summit', Gaborone, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

[8] Implementation of the Rome Statute of the ICC Act 27 of 2002, section 4; the Constitution of South Africa, 1996, sections 231 and 132.

[9] International Crimes Act, 2008.

[10] International Criminal Court Act, 2010.

[11] Sections 30 -32, Penal Code of Mali, http://www.preventgenocide.org/fr/droit/codes/mali.htm (accessed on 26 July 2012).

[12]http://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/rdonlyres/A245A47F-BFD1-45B6-891C-3BCB5B173F57/0/ReferralLetterMali130712.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2012).

Chacha is a researcher at the Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria and author of Prosecuting International Crimes in Africa. He studied in Pretoria and Dar es Salaam, was a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Dodoma, and an advocate at the High Court of Tanzania.