For most who attend the UN General Assembly every September, the general debate (not really so, but a seemingly endless line of speeches, one by each member state of the United Nations) is the least important activity of the two weeks. The General Assembly is a public statement of the primary concerns of a nation and often a series of barbs, accusations or a call for peace, depending on where a particular country is on the political spectrum and whether it sees itself winning or losing a war or a public relations battle. The appearance of Pope Francis on the agenda added some spice to the General Assembly but even that seemed anticlimactic after his appearances in Washington, DC. The Pope’s message was one of hope, as it must be, and it was encouraging that he was willing to address the issues of the day beyond pastoral care. His influence on individuals is likely greater than on the nations populated by the same individuals. One is often reminded of the question that Stalin once was supposedly asked by an aide about whether the Soviet Union should worry about the influence of the Church on Eastern Europe, and especially Poland. He replied with disdain, “How many divisions does the Pope have?” dismissing the worries of his aide. It is still difficult to discern the line between the influence of individual actions versus the role of the State. Beyond convincing John Boehner to resign as Speaker of the House and seek a new role in life, it is always difficult to know the influence of the Pope on global decisions or as some say, to understand the mystery of the power of faith. On the other hand, the Church still stands and the Soviet Union has disappeared.

My sense of this particular General Assembly was there was a subdued nature to it all. After all, it was originally intended to be one of celebration, for the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) declared with great fanfare and optimism at the 2000 Special Session preceding the General Assembly were to all be achieved by 2015. Perhaps 9/11, almost exactly a year later changed all that and the possibility of ever achieving the goals in such a time span, bringing into focus the power of individuals versus the power of the State in a different way than the Church views the world. In reality, most of the goals set 15 years ago have not even reached 50 percent of their target, and there was not a lot said about the MDGs. New goals were set, but one wonders how much belief exists in the next set of markers. Certainly the rhetoric was much more measured at the United Nations than it was 15 years ago. The world is a much more sober place than when we entered this Millennium with optimism and a New Year’s euphoria in every time zone.

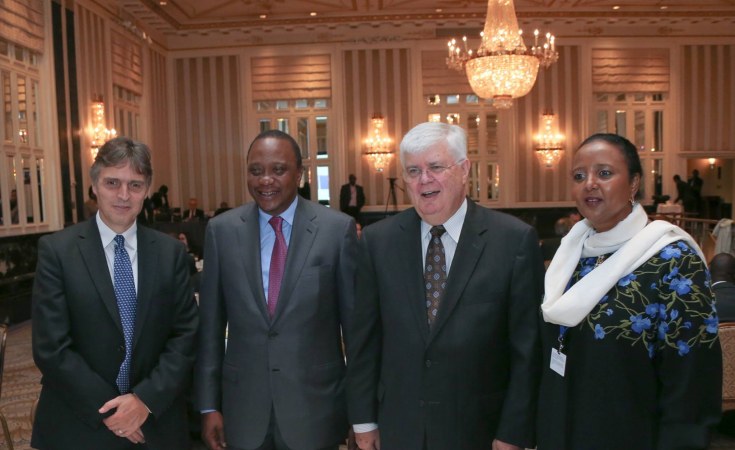

Really, the most important events during the UN General Assembly are the private meetings around town, where a Putin meets an Obama (apparently not a terribly successful or happy occasion), or investors meet with Heads of State and Ministers trying to work a mutually beneficial deal. The latter will not be easily known. Terms are seldom revealed. Government-to-Government meetings abound, and these meetings, too, beyond the photo ops, are held, perhaps necessarily, in secret. Various non-governmental organizations and business organizations, such as the Corporate Council on Africa, line up meetings with officials at the request of their members, or hold public events with Heads of State in order to give some countries more visibility or to respond to requests from Nation’s emissaries to help fill their President’s schedule.

For Africa, I saw less benefit from this General Assembly than from previous Assemblies (I have been to at least 22 General Assemblies). The calamities of the Near East and parts of North Africa have certainly overtaken development issues, as have the realities of climate change, whether long-term or cyclic. The growing clouds of conflict in various parts of the world also darkened the mood throughout the city. Again, if there was progress, it was to be found in the private and semi-private meetings around town, and these are the harder results to discern. Still, one often also sees some of the real issues more clearly in these meetings.

For instance, in East Africa, one learns about LAPSSET (Lamu Pipeline through Southern Sudan and Ethiopia Transit), a major project designed to link transportation and oil transport, as well as create major port developments for East Africa. The project is a game changer and close to signing between the countries and the hopeful contractors - no easy task given the number of nations involved. (More than two nations involved in any issue always increases geometrically the complexity and difficulty of achievement in Africa.) It is near agreement, but the entry of China with a competing project has further added to the complexity of getting to ‘yes’, and brought into what should be a relatively simple project the ugly head of geopolitics, making Africa once again the proxy battleground of superpowers, pawns on a global chessboard.

There are messages of hope from Africa as well as from the Pope. Tiny Namibia shows signs of new developments important to global shipping, Mozambique now has some of the largest proven reserves of natural gas in the world, and there is a growing sense of regional cooperation in East Africa and West Africa, despite the plague of Boko Haram, extremism and disease. It is more hopeful a region than not.

In the end, the General Assembly is an opportunity for leaders to have many bilateral meetings in a single time period and perhaps to return to their nations with some renewed optimism and a deeper and grounded reality. Perhaps the role of the Pope is to frame the parameters of optimism and reality. We live in complex times where the hopes of individuals increasingly come into conflict with the goals of the State. It is so in Africa as much as anywhere else in the world. The challenge in Africa will be to keep the hopes and expectations at a realistic level, for the development will be uneven and not always successful, despite the best of intentions, as the last fifteen years have shown.