"Egypt is for all Egyptians; all of us are equals in terms of rights. All of us also have duties towards this homeland. As for myself, I don't have rights. I only have duties."

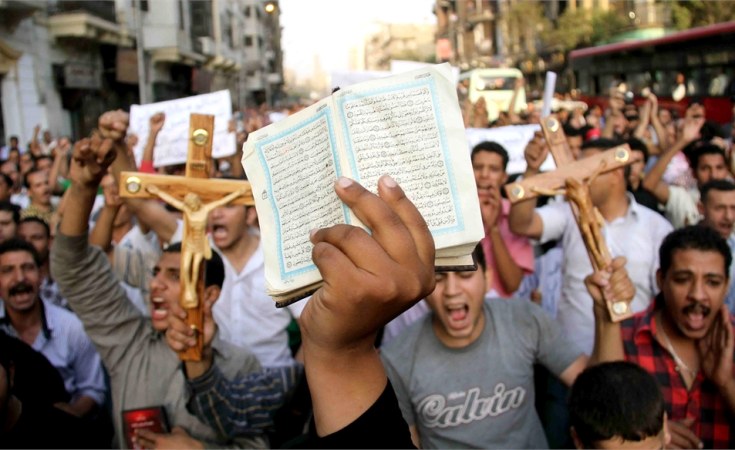

Mohamed Mursi's first speech on June 30 marked a historic event in Egypt, where the nation watched the Muslim Brotherhood candidate being sworn in as the first competitively elected president in Cairo. Whilst the dominant issue for many remains what kind of government it will have - Mursi is currently locked in a stand-off with the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) - many minorities in the country have reacted miserably to his presidential victory, especially Coptic Christians, the largest minority group.

Despite the promise of an "inclusive" Egypt in his inaugural Cairo speech, Coptic concerns about the new president's Islamist background remain. Rooted in the ideology and objectives of the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamic party founded in 1928 as part of the anti-colonial movement, the key principle of the Brotherhood was, and still is, to promote Islamic piety as the organising force in Egyptian society. Many Copts fear that attempts to create such a society will naturally discriminate against them.

Discrimination and distrust

Copts, who make up around 10% of Egypt's 82 million population, have witnessed Egyptian society outwardly Islamise in recent decades with an increase in displays of piety. The Brotherhood's influence could be felt not only in social attitudes but in the constitution.

Dominance of the majority Islamic faith was assured when Mubarak's predecessor, Anwar Sadat introduced Article 2 in 1971 which states: "Islam is the religion of the state, and the Arabic language is its official language. The principles of Islamic law are the chief source of legislation."

For years human rights groups have been reporting attacks and molestation of the Coptic minority and also instances of their forced conversion to Islam, a conversion carried out with intimidation, violence and rape. Churches and monasteries have been targets of violent attacks including some notable incidents such as the 21 victims of the Koshesh massacres in 2000, the anti-Christian riots in Alexandria in 2005 and the mob attack on a Coptic church in Cairo four years ago.

This same story of despair has continued in recent years. Several Copts lose their lives in 2010 during the Nag Hammadi massacre, as they left church following midnight mass on January 7, the date of the Coptic Christmas. New Year's Day in 2011 saw at least 21 Copts killed in a church bombing in Alexandria, which triggered protests that contributed to the nationwide uprising which began on January 25, 2011.

And there is nothing new about Copts complaining about daily discrimination on the streets and in the workplace, being prevented from promotions and holding high positions. During Mubarak's regime, Copts were underrepresented in parliament, with only six of 444 members between 2005 and 2009. At the same time, the Muslim Brotherhood stated in their 2007 electoral program that Copts were not allowed to run for presidency.

Government officials have done little to quell the violence and many Copts believe the Mubarak regime and Islamic extremists have been responsible for the increasingly fragile state of Egypt's Christians. Others believe that this has been exacerbated since the revolution with the SCAF accused of allowing chaos in order to bolster their position as guarantors of security and stability.

Elections, Results and the Rise of the Muslim Brotherhood

The first round of elections saw Coptic support for secular candidates including Amr Moussa, former foreign minister and secretary general of the Arab Leagure, Hamdeen Sabahi, leader of the Dignity Party, and Ahmed Shafik, an Air Marshal, minister and briefly prime minister under Mubarak.

In the election run-off, Mursi's rival, Shafik, unquestionably took most of the Coptic vote, even though they suffered under the Mubarak regime. But with the long mistrust of Islamists, Shafik was widely seen as the lesser of two evils. The Cairo rumour mill has added to tensions with rumours, reported by journalist Robert Fisk, of rigged ballots. For example, Caroline Morcos, an activist told Think Africa Press: "I believe Shafik really won, but they let Mursi win just to keep the country stable as the Muslim Brotherhood had destructive plans if they didn't win."

After Mursi's victory, many Copts now fear for their freedom and safety, while some are willing to give the new president a chance. But concerns remain high as Matthew Aziz, a Coptic doctor in Cairo said: "This result has caused more concerns for Copts especially in Upper Egypt regarding their financial future and concerns to those in big cities about their daily lifestyle, including their freedom to live as they used to."

A long journey

The Coptic feelings of, but not entirely baseless, paranoia stems from a lack of control over their destiny. They feel their future is in the hands of President Mursi, his interpretation of what an Islamic society should look like and his ability to deliver it.

The Copts may have nothing to fear. Mursi and the Muslim Brotherhood are highly unlikely to use the ultra-conservative Hanbali School of jurisprudence dominant in Saudi Arabia, they are not Salafi literalists and Sharia law can be interpreted to be based on principles of social justice. But, as Mina Naguib, human rights researcher and graduate medical student based in the UK explained:

"Some aspects of Islamic law can be applied positively depending on how Mursi and his parliament choose to interpret it, for example basing policy on broad ideas such as social justice. However, there remains relatively little modern precedent for the positive application of Sharia with respect to personal freedoms."

Mursi is under pressure to calm the West's fear about Islamic politics. Reassuring news of his intentions to appoint a Coptic Christian as a vice president, and the promise of a modern and democratic Egypt is a move that would demonstrate a show of harmony and could dispel fears of the Muslim Brotherhood. But sceptical observers suggest it is nothing more than false display of diplomacy for the benefit of the international community while, in fact, the Muslim Brotherhood's real agenda is undemocratic, and will cause greater sectarian tensions and discrimination against Copts.

Mina Naguib said: "Muslim Brotherhood has consistently refused to cooperate and have sold out the revolution for their own gain. As such pro-revolutionary folk don't trust them anymore. It's a crude measure, but compare their parliamentary performance to their presidential one - a significant drop in support in just a matter of months."

According to a report by the Egyptian Federation of Human Rights, 93,000 Coptic Christians have fled the country since March 19, 2011 and the number is estimated to increase. Bishoy Kirolos, a church volunteer based in Shobra, who is determined not to be driven away, told Think Africa Press: "Many Copts are very depressed and a lot have emigrated already. But I believe God will protect us and nothing bad will happen."

With discrimination on-going and trust between many Copts and the Muslim Brotherhood are at a low point, Mursi has his work cut out. He not only has to protect the Coptic minority, but live up to his democratic rhetoric, he has to gain their trust. After the power struggle with SCAF, this may prove his greatest challenge.