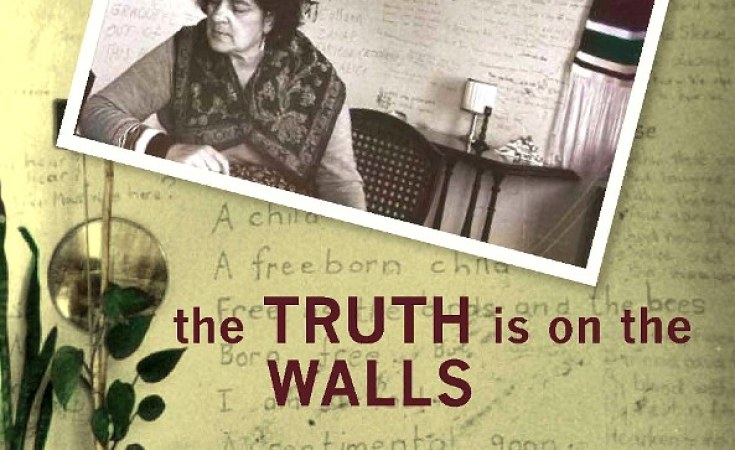

Excerpts from "The Truth is on the Walls," the story of Naz Gool Ebrahim a civil rights activist, from District Six, Cape Town, who struggled against the forced removal of her community, which lay adjacent to the Cape Town city centre from the 19th century until it was destroyed by the apartheid government as it enforced residential segregation.

In the first excerpt, co-authors Shahena Wingate-Pearce, the daughter of Naz Gool Ebrahim, and Donna Ruth Brenneis, an American writer, introduce the book with an explanation of the rich heritage of South Africa's Coloured community:

This historical nonfiction speaks on behalf of Coloured people in South Africa. Once known as the 'Peanut Butter People', they were never White enough or Black enough. Their question was where do we belong? Today, South African racial groups merely consist of Black and White. During the apartheid regime, there were three classifications: 'the White tribe' who called themselves Europeans; 'the brown tribe', known as non-Europeans; and 'the Black tribe' called Natives. (Afrikaners made no distinctions between the Black tribe and the aborigines (indigenous people) – the Khoi and San.) One's classification determined where one would live, the kind of education one would receive and class privileges.

The non-Europeans were subdivided into Asiatics (subdivided again into Chinese, Japanese and Indian), Cape Malay, Coloured and mixed (a White parent and a parent from the Black or brown tribe). It was the Coloured and mixed group of people who were referred to as the 'peanut butter people', because they were comfortable in the middle, not taking a stand, principally because of the brutal treatment and/or imprisonments they watched their leaders experience under the

laws of apartheid – leaders like Cissie Abdurahman Gool, George Peake and members of the Gool family, to name but a few. The Coloureds' actual skin tone ranged from dark brown to pink. They were a complex mix of cultures and ethnic groups. A large percentage lived on prime property, situated in the heart of Cape Town, which was known as District Six. It was a vibrant, humane and ethnically mixed community of Coloureds, a few Blacks and some Whites that was not simply a group of buildings but a way of life until the apartheid Government declared the District a White area on 11 February 1966, under the Group Areas Act. Along with the Black Africans who had endured forcible removals for years in the townships, the Coloureds were now being forced out of their homes, once again, but this time the removals involved 60,000 people who were to live in the barrenness of the Cape Flats.

The apartheid Government and its Group Areas officials destroyed an entire community in three phases, with the last residents leaving in 1982. For 14 years, people watched the destruction as families, friends and their beloved community were annihilated by the Government's bulldozers. By 1988, five to six hundred Whites lived in the District. People declared the area a monument to greed and absolutely no one, in any group, wanted to touch the deep scar that had been left in the centre of Cape Town. Today, the land surrounding District Six is predominantly empty. Inasmuch as it was the Group Areas officials who left the scar against the face of Table Mountain forever, we believe the Coloureds' story needs to be told so that District Six and the land upon which it sits can heal.

In these excerpts, South African journalist John Battersby, who reported on the final stage of the forced removal, writes in the book's foreword that the cabinet minister responsible, P.W. Botha – who later became president – tried to justify his action by declaring District Six a "slum":

Even then... Botha... was aware that the resistance the apartheid Government would face in trying to make District Six fit its racial grand plan would be of a different scale and duration than anything it had attempted before. Declaring the area a slum was an attempt to defuse that resistance and give the decisions a fig-leaf of justification in the name of urban renewal. It is true that there were many absentee landlords collecting rent on crumbling buildings and the area was overcrowded. However, it always looked more like ethnic cleansing than urban renewal.

In deciding to destroy District Six the minority Whites-only Government was embarking on the removal of the last settled Coloured community in the heart of Cape Town.

District Six was always more than just another neighbourhood. With its multi-racial character, spice-filled markets, and exotic restaurants and night clubs, its strong sense of communal identity, its street gangs and proximity to the port, it was a microcosm of everything that the apartheid grand plan wanted to prevent. It was a relatively harmonious racial melting-pot in a country where racially diverse and multi-cultural neighbourhoods were not the norm.

One of the more memorable pieces of graffiti that adorned the walls of the doomed District and proliferated as the slow-motion destruction gained momentum read simply: 'You can take the people out of the District Six but you can't take District Six out of the hearts of the people.' It was a bold and defiant message that captured the spirit and determination of its residents.

The systematic demolitions and the constant sound of bulldozers and sledge hammers gave the District the atmosphere of a battleground making way for a graveyard. The piles of rubble and wrecked buildings became a symbol of the relentless social engineering that would systematically rid every multi-racial town and neighbourhood throughout the country of racial mixing.

Segregated neighbourhoods were created with Whites getting the prime land and Coloured and Black South Africans usually being moved to far-flung townships beyond the reach of community facilities and municipal services, and often adjoining sewerage works and refuse dumps.

The law used to 'authorise' these forced removals nationally was euphemistically known as the Group Areas Act, and was predicated on the insidious and patronising notion that people would be better able to progress if kept apart from other race groups. Apartheid was raw racism implemented by violent means and dressed up as 'separate but equal'.

What I witnessed in those last years of demolition, between 1977 and 1979, was nothing short of a spiritual genocide. A holocaust of the soul. Reporting on the constant human tragedy and brave resistance of unarmed residents gave me a sense of moral clarity, which defined my conceptual framework for reporting on the inhumane and unjust system of oppression known as apartheid.

In terms of the grand scale of apartheid, the Group Areas Act, which applied only to Coloured, Asian and White communities, was responsible for the forced removal of some 130,000 people nationwide. Shocking as this statistic is, it was a mere blip on the apartheid radar when compared with the estimated three million or so Black South Africans who were forcibly removed from their land and homes during the apartheid years under the various Land Acts, which reserved 13% of the land for more than 80% of the population.

There was something about the destruction of District Six that was uniquely evil. It has something to do with the fact that the victims shared the same culture and language as the architects of apartheid, and they aspired to Western values and culture. Their only crime was that their skin colour was darker.

Another memorable graffiti line was: 'You are now entering fairyland', but when the sledge hammers began their work the community declared District Six 'cursed ground'.

Thirty years later it remains almost a wasteland, apart from a university of technology built in the dying days of the apartheid Government and a few dozen houses built with the sanction of the Hands Off District Six committee, made up of former residents who are now mostly in their 60s and 70s.

A further 40 houses are earmarked for construction following decades of infighting between former residents, rival political parties and Government authorities, and the painstaking process of changing the law to allow former tenants and owners to be beneficiaries of the land restitution process.

As the sledge hammers came down on house after house in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, one of the most passionate and uncompromising voices of resistance to the forced removals was that of the late Naz Gool Ebrahim, a descendant of Cissie Gool, one of the District's most distinguished civic leaders.

Naz, who rejected repeated attempts over a decade to lure her to leave the District for a more affluent home in a Coloured group area, was the voice of a community bludgeoned into submission by an ideological system that did not care for human needs and sensibilities. It resorted to bizarre apartheid laws to justify its actions.

In an interview in 1978, Naz told me that she had been resisting an offer of a better house outside the District for the past eight years. The alternative, the White official had informed her, was to face forcible eviction under apartheid.

'That official's words tore into my flesh and have remained with me ever since,' she said. 'The only way I could give vent to my pain was to tell the world what District Six meant to me.'...

[Naz's story]... is a microcosm of the bigger South African story, and a reflection of the quality and diversity of the people who helped create a nation which is still in the making. It traces the history of the first indigenous life in the Cape, and it tracks the long and painful struggle for political and social justice and human rights. That struggle is by no means over...

Many of those who remember living in the District still believe it will play a critical role in the development of a shared future in South Africa. That chapter is still to be written. In the meantime, the wasteland stands as a monument to the injustice and inhumanity of apartheid...

The contribution of South Africans like Naz Gool and her ancestors have made an important contribution to the momentous events leading up to the first democratic elections in 1994 which gave South Africans the opportunity of a new beginning.

We all have a responsibility to honour Naz's memory by ensuring that the wasteland that marks the site of District Six, many years after its death knell was sounded, becomes a living monument of hope for a shared and better future for all.

The TRUTH is on the WALLS by Naz Gool Ebrahim, Donna Ruth Brenneis and Shahena Wingate-Pearse is published by David Phillip/New Africa Books, Cape Town

Available online at:

http://www.exclus1ves.co.za/books/The-TRUTH-is-on-AuthorNaz-Gool-Ebrahim~AuthorDonna-Ruth-Brenneis~AuthorShahena-WingatePearse-/000000000100000000001000000000000000000000000009780864867391/