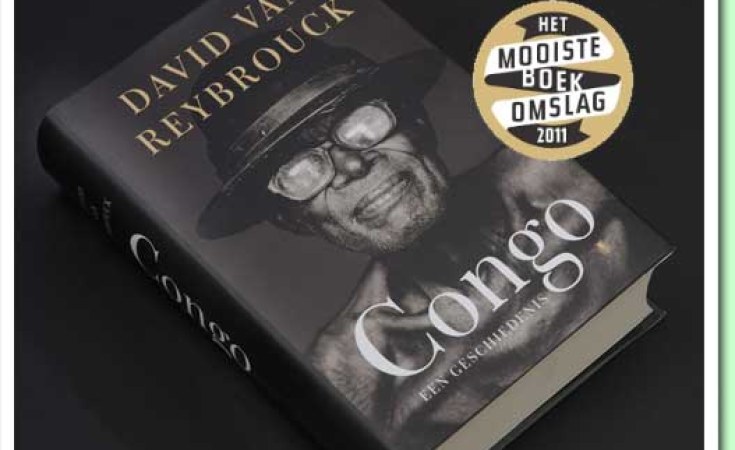

David Van Reybrouck's epic history of the Congo brings to life and honours the heroic lives of ordinary people as well as the extraordinary lives of the country's heroes.

The Congo is everywhere. Quite literally. Open up your smartphone, laptop or game console and inside you'll find a small green plate which looks like a miniature model of a futuristic power plant.

The brightly coloured beads are capacitors, which are made of tantalum. Tantalum is a metal extracted from the mineral coltan, and most of the world's coltan lies in the soils of the eastern Congo.

The pieces of the Congo found in virtually all digital products today may be tiny in size, but their significance for millions of people in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and wider world is huge.

Tantalum connects American teenagers with Chinese factory workers, multinational mining conglomerates with artisanal Congolese miners, and, to the detriment of relations in the DRC's Ituri region, Hema pastoralists with Lembu farmers.

The eastern Congo has been particularly unstable and insecure since 1994, when thousands of genocidáires and Hutu refugees fled from across the border from Rwanda. But in the late-1990s and early-2000s, a coltan rush left its mark on the shape, size and direction of the conflict.

Sony was about to launch its PlayStation 2, and Nokia and Ericsson wanted to introduce a new generation of mobile phones, driving up the demand for the valuable and heat-resistant tantalum. In less than a year, the price for a pound of coltan rose from $300 to $3,000, and warlords and rebels in the eastern DRC quickly realised the potential of the resources under their feet.

The war in the eastern DRC did not start with profit motives in mind. Rather, it was largely driven by Rwanda and Uganda's desire to overthrow the regime in Kinshasa through an alliance of makeshift rebel forces.

However, when this proved impossible - partly due to the support the regime was receiving from neighbouring countries and the local population's antagonism towards the rebels - Rwanda and Uganda satisfied themselves with having de facto control over the east. From about 1999 onwards, they controlled the territory and exploited the mineral resources through their local militia proxies.

Mineral riches such as coltan were not a root cause of the conflict, but they did serve to prolong it for the simple reason that many parties - from big multinationals to local artisanal miners - were profiting from it. Conflict and instability continued to reign supreme because of the financial opportunities they made possible.

As David Van Reybrouck asserts in his newly-translated book, Congo: The Epic History of a People, "Failed nation states are the success stories of a global neoliberalism that has spun out of control."

Everyday facts of extraordinary lives

The history of the coltan rush is one of many chapters of Congolese history covered in Van Reybrouck's brilliant and magisterial biography of the country.

It was first published in 2010, 50 years since the country's independence from Belgium, and by which time the average life expectancy had dropped to below 45 years. "The country turned fifty, but its inhabitants no longer did," remarks Van Reybrouck, envisaging the trouble he would have in finding living witnesses to the country's colonial history.

Indeed, Van Reybrouck would have little difficulty finding written sources from European missionaries, tradesmen and slavers who first arrived in the country in 1482, but it was the personal testimony of Congolese people today that was of most interest to him.

He wanted to hear from the people whose life stories collectively make up the turbulent history of the African giant. But rather than merely asking his interviewees about their opinions of times past, Van Reybrouck wanted to know what his informants ate, what clothes they wore, what their houses looked like when they were children, and whether they went to church.

It is from this tangle of everyday facts of life that Van Reybrouck spins a fine thread with which he eventually knits together this detailed and well-researched biography, thoroughly rooted in the lived experience of the Congolese.

However, before we get to the current day, Van Reybrouck takes the reader on a whirlwind journey that starts at the very beginning - namely, from the earliest archaeological evidence of human presence in the region some 90,000 years ago.

In the introduction, snapshots of an imaginary 12-year-old boy's life carry the reader through the country's last ninety millennia, from the earliest archaeological findings in the shape of bifaces found close to Lake Edward and the first written account mentioning the Congo about 4,500 years ago - referred to by the Egyptians as the 'Land of the Spirits' - to the time of Don João, king of the Bakongo in the late 15th century who admitted the first Portuguese missionaries into his kingdom in the hopes of revealing the secrets of the Europeans.

Through six hundred pages, the reader goes on a guided tour through the Congo's history, sometimes hovering thousands of miles above the country, viewing domestic events in the perspective of global politics, colonial aspirations and Cold War proxy-hostilities, before descending to the street level and the stories of individuals whose lives shaped and were shaped by this juggernaut of a country.

When history comes to life

In Congo: The Epic History of a People, one follows not just the lives of people whose personal stories would have been lost in the maelstrom of history were it not for Van Reybrouck's eye for detail and interest in the everyday, but also those of the country's movers and shakers.

In one episode, for example, the reader tags along with Patrice Lumumba and Joseph-Desiré Mobutu, two young men who only recently became friends.

One is a beer-seller, the other a journalist. It is 4 January 1959, a week after Lumumba made a speech about his trip to the newly-independent Ghana to a crowd of thousands whom he left chanting 'Dipenda, dipenda!', meaning 'independence' in Lingala.

Now, the young revolutionaries are together on a motorbike. Mobutu is driving while Lumumba has taken the back seat. Manoeuvring the Kinshasa traffic neither of them knows that this day will be a turning point in history, the day on which the Congo's native sons and daughters will finally say no and violently rise up against their colonial masters, a day that will start a series events that will see each of them lead the country for a time and leave a deep imprint in the region's history.

Almost 50 years later, the reader finds themselves with Van Reybrouck in the eastern Congo. The scene is a darkened office in Goma. The muffled sounds of the streets outside enter the room where he listens to Masika Katsuva, a 41-year old Nande woman, as she recounts the horrors that befell her and her family in 2000:

"..the soldiers entered. It were Tutsis. They spoke Rwandan. They ransacked everything and wanted to kill my husband. 'I've given you everything,' he said, 'why do you also have to kill me?' But they said: 'Big traders we have to kill by knife, not with a gun.'

They had brought machetes. They hew in his arm. 'We have to hit hard,' they said, 'the Nandes are strong.' They slaughtered him as if they were in an abattoir. They removed his intestines and his heart."

While speaking to Van Reybrouck, Katsuva continuously scratches a vein in the wood of the table with the top of her ball-point pen. After the soldiers had cut her husband into pieces, she recounts, she was forced to collect the different parts of the body and pile them up, before the twelve soldiers took turns in raping her. It wasn't long before she lost consciousness.

Katsuva went on to run a small NGO, Synergie des Femmes, which provides shelter for Congolese women who have been subjected to sexual abuse and violence.

But this put her in the firing line, and in 2006, she had to relive the horrors she had suffered before, but now at the hands of the men under the command of the Rwandan-backed Tutsi warlord Laurent Nkunda who sought her out because of the role she played in comforting and aiding other victims of rape.

"I want to kill Nkunda. God forgive me. If that would mean my death, then at least I would have found peace," she says, while continuing to scratch at the wooden table as if trying to scratch something else away.

The centenarian and G-strings by the thousand

Reading Congo: The Epic History of a People, it is clear that the author is not your typical historian dryly publishing his findings, but a literary artist with a pen almost as sharp as Lumumba's tongue.

Van Reybrouck captures his reader's imagination and brings the history of the Congo to life as if it were a thriller.

From génocidaires to street vendors, child soldiers to ministers, boys to messieurs, religious leaders to missionaries, and warlords to pop stars, the book honours the heroic lives of ordinary people as well as the extraordinary lives of the country's heroes.

Opening with the unbelievable story of Papa Nkasi, a man who claims to have been born in the year "mille-huit cent quatre-vingt-deux" (1882!) and ending with the vibrant Congolese community in the Chinese metropolis of Guangzhou where G-strings are only sold by the thousands and young Congolese homosexuals find the freedom they lacked back at home, the book is as complete a history of the Congo as anyone could wish for.

Every day, hidden in our tablets and smartphones, mp3 players and laptops we all carry small pieces of the Congo with us and this monumental work provides some fundamental and invaluable insights into the lives and wars that have been won, lost, lived and spent to make this happen.

This important book sheds a bright light on a country which for far too long has been denied its proper place in both our obscured history and our hyper-connected present.

[Note: the author read the book in its original Dutch version and quotes from the book are the author's own translations.]

Joris Leverink is a freelance writer with a background in political economy and cultural anthropology.

He has recently finished an MSc at SOAS in London, where he specialised in the history of the Malian political crisis. He is also an editor for the revolutionary online magazine ROARmag.org. You can contact him via Twitter @Jorislever