Githurai — A herd of camels have become a low-carbon food waste recycling system in a Nairobi market - and they produce milk

Vegetable seller Jacinta Nyokabi used to fret about what to do when her tomatoes began to rot at her stand in Githurai's open air market.

She could dump them in the market's drain to get rid of them or just leave them sitting in a corner. Either way she risked fines and the ire of market authorities.

"If I throw away waste, county officials will accuse me of contaminating the market because rotting fruits and vegetables smell and attract rats which spread diseases," complained the 32-year-old mother of two.

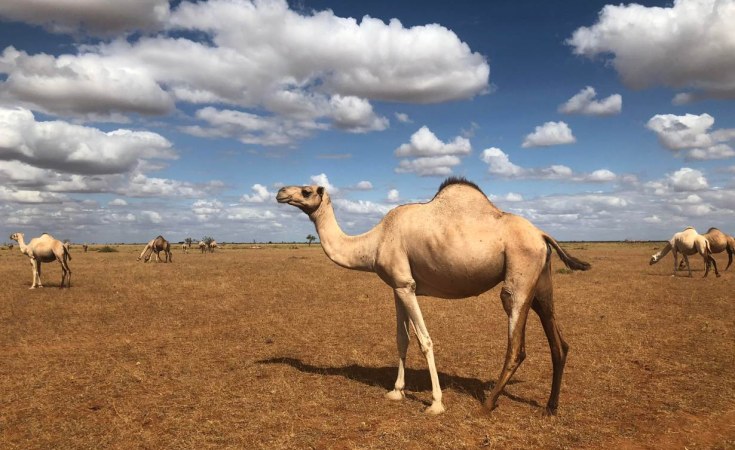

But now there are eager customers for her rotting tomatoes: A herd of 20 meandering camels, brought in from arid northern Kenya to act as garbage disposals for the market's food waste.

"The camels feed on everything that we give them and so the food is not dumped away," said Nyokabi, who has been selling fruits and vegetables at the Kiambu County market, northeast of Nairobi, for two years.

The market's new low-carbon food waste recycling system is the work of Stephen Kariuki, who owns the animals and herds them through the market each morning.

FOUR-FOOTED RECYCLING

To earn a living, Kariuki used to rummage through the many landfills in Nairobi for plastic bottles, which he would sell to private waste recycling businesses.

"Everyone wants plastics so that they can make other things from them," says the 32-year-old who grew up in the Mathare slum, on the fringes of the capital. "But nobody is interested in rotting food."

That changed when he hitched a ride to Northern Kenya as a loader for a timber merchant. While there, he noticed the hardship camels go through as they scratch for fodder from drying rangelands.

"I remembered the fruits and vegetables that were wasting away in Nairobi and said to myself that I could try my luck with camels," he remembers.

With $120 in savings from selling plastics he managed to buy the first camel and transport it to the Githurai market in January 2016. Since then, Kariuki has made more trips to Northern Kenya and raised an urban herd of about 25 camels, as well as a few cows and goats.

"I prefer camels because they do not stray away to destroy people's property," he said. "Camels also like the fleshy market waste which they seem to like more than the parched arid vegetation."

The camels produce milk, which Kariuki can sell, and other income as well.

"A well fed, healthy camel like this can fetch as much as $1,000," said the smiling herder as he showed off his beasts. "Their milk is very nutritious. During the weekends, I fit them with riding gear to give estate children leisure rides at a fee."

So far, Kariuki has few competitors in his new market niche - at least for now. And traders say they are grateful that the passing dromedaries are saving them money and worries.

NOT FOR EXPORT

Nyokabi, perched on a seat in a shed roofed with the flapping remains of paper cartons, said the camels were particularly useful in a market without any cold storage or formal waste disposal system, despite traders paying a 50-cent daily fee to the county.

Market traders can face fines of up to $1 a day for dumping their rotting wares, she said.

According to Asaah Ndambi, a researcher with the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), at least 3,200 tonnes of waste are produced in Nairobi every day. Organic waste, especially from farm produce, accounts for 2,000 tonnes of this figure.

A share of the waste comes from farms that produce vegetables, fruit and flowers for export.

A 2015 report by Feedback Global, a London-based organisation that combats food waste, said many Kenyan farmers grow fruits and vegetables with the expectation of exporting the produce to the EU market, to take advantage of attractive prices there.

However, over 30 percent of the food is rejected while still at the farm due to EU regulations and standards that bar farmers from exporting food that is not the right size, colour, or shape, or that is simply unattractive, the report said.

"Most of this food ends up being sold in city markets where demand for fruits and vegetables is still high," argued economist Robert Mudida, a professor of political economy at Strathmore Business School in Nairobi.

"Poor roads make the food to be knocked around and so by the time it reaches the market it has started going bad. Poor storage spoils what freshness was remaining of the product," he added.

Reporting by Kagondu Njagi; editing by Laurie Goering