Somalia, which has not had a functioning central government in more than two decades, is experiencing an upsurge in violence and increased civilian casualties.

Clashes have intensified between al-Shabaab insurgents and the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) led by Sheikh Sharif Ahmed , which enjoys international recognition but controls limited territory in and around the capital, Mogadishu. Troops from Uganda and Burundi comprise the 6,300-strong peacekeeping mission from the African Union supporting the TFG – the justification provided when Shabaab claimed responsibility for the bombings in the Ugandan capital, Kampala, on July 11 that left more than 70 people dead.

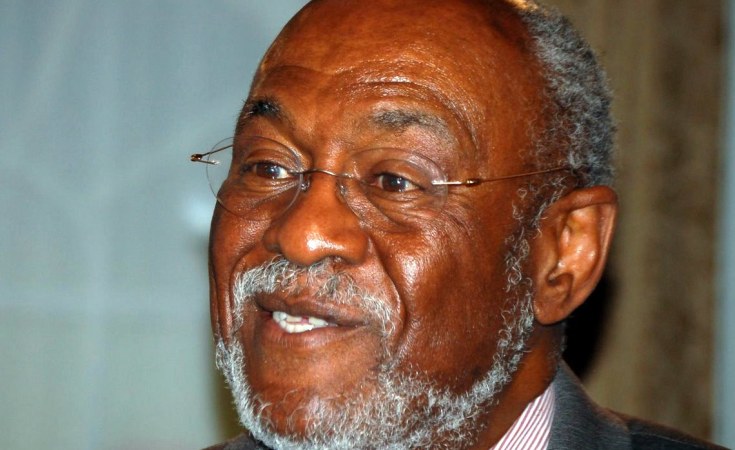

U.S. assistance for the AU mission, known as Amisom, could be enhanced if the African participants ask for increased logistical support and training, Gen. William Ward, who heads the U.S. Africa Command, said in Washington this week. Current U.S. aid for the TFG includes a range of non-lethal equipment, plus a significant amount of ammunition, according to U.S. officials. Urgent action is needed to address instability in Somalia, according to U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Johnnie Carson, the Obama administration's senior Africa policymaker. In the second part of an AllAfrica interview this week, he said continued insecurity poses a danger not only to the 10 million people living there, but also to the region and, as piracy directed at ships from around the world continues unabated, to the international community. Excerpts:

In the aftermath of the two bombings in Kampala on July 11, what is the United States doing to assist Uganda?

Let me start by saying that we in the United States were deeply saddened by the double bomb blasts that occurred on the last night of World Cup in Kampala, and this event in Uganda shattered what should have been an Africa-wide sense of achievement related to South Africa's successful holding of the Cup.

We believe that Uganda was probably targeted in large measure for its participation in Amisom and its support for the Djibouti [peace] process and the TFG, the current Somali government. While the information is still coming in, it would appear that elements linked to Shabaab were responsible. This event in Kampala focuses not only African, but international attention on the problem that exists in Somalia.

Somalia is a problem which is three-dimensional in nature. Somalia, for the last twenty years, has been a state without a strong, effective central government; it is a state which [has] virtually imploded; a state that has been racked by enormous civil strife, famine and recurring humanitarian problems. It is a state that has been fragmented into three large units: Puntland, Somaliland and south-central Somalia – Somalia as we know it, based out of Mogadishu. And certainly in southern Somalia we have seen episodic levels of extreme violence with warlords preying on citizens and relief groups, and now, violent extremists doing the same thing. Somalia has collapsed in on itself.

The second dimension is regional. Somalia's problems have overflowed into the region. Today, Kenya plays host to 170,000-plus Somalis in the Dadaab refugee camp in the northeastern part of the country. International aid agencies say that between 5,000 and 6,000 Somalis every month cross from the deteriorating situation in south-central Somalia into Kenya. Those who don't make it into Dadaab become a burden on the Kenyan state. Many migrate to Eastleigh, a major suburb inside Nairobi which is largely a Somali community.

You have Somali refugees in Ethiopia, Djibouti, and even further afield in places like Uganda and Tanzania. This is an enormous burden on all of the refugee-receiving countries, but it's not just the refugees who are causing this burden. We see enormous illegal arms flows out of Somalia into the region. We see illegal commercial items moving out of Somalia into the region. People talk, in many parts of eastern and southeastern Ethiopia, about illegal smuggled goods coming through the ports of Mogadishu and Kismayu ending up in Harar, Dire Dawa and Kulubi, undercutting the legitimate commerce of the region. This is true in Ethiopia, and it's true in Kenya. You have illegal goods coming in, illegal arms coming in, flows of people – all creating disturbances and having a negative impact.

We also have seen the problem bleed into international piracy in the Red Sea. Somali piracy is a direct result of the lack of centralized, effective governance in the country, the absence of a police force, the absence of a judiciary and the rise of impunity; also the absence of an alternative source of income; the absence of a formal and informal economy capable of providing jobs. If there were economies providing jobs, if there were a judiciary and a police force, security services to manage and jail people for piracy, we wouldn't see piracy going on. But as long as there is a breakdown of such enormous proportions across Somalia and Puntland, we will continue to see piracy.

Beyond piracy, we see a multiplicity of problems flowing throughout the region. Violent extremism is an issue of international concern. The bombings in Kampala are a result of violent extremism. We know some of the leaders of the al-Qaeda east African cell were responsible for the tragic bombings of the American embassies in Dar-es-Salaam and Nairobi on August 7th, 1998, and were responsible for the Paradise Hotel bomb blast in November 2002 and the attempt to shoot down an Israeli commercial plane on the same day. It is no longer possible for the international community to ignore the danger from a continued absence of security and governance in south-central Somalia.

What does it mean that the threat from Shabaab does not seem to be lessening? Do you believe that backing the TFG militarily and diplomatically can be effective?

I think it is the correct policy. The policy that we pursue towards Somalia is supported by IGAD [the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, an organization of six eastern African nations]. It is a policy that was designed and orchestrated by the people of Somalia and supported by the region to bring together a transitional government that would bring in as many clans and sub-clan groups as possible.

We think that we need to do as much as we possibly can to keep the Djibouti [peace] process – and the TFG which flows from it – moving forward. There is no question that the TFG has to do more than it's done in the past. It has to not simply be a government in name only, but it has to be a government that provides services to the people; a government that is working towards stability; a government that is trying to be inclusive and bringing in more groups opposed to al-Shabaab and committed to stability.

It has to provide a clear alternative to al-Shabaab. The people of Somalia are largely moderate followers of Islam – people who desire a stable and peaceful country; people who are desirous of the right to have economic opportunity and prosperity. Shabaab does not offer that. I think Shabaab provides an extremist, radical, draconian alternative. I don't think Somalis want it. I don't think Somalis deserve it.

Why hasn't the TFG been effective?

The TFG needs to improve its game. It needs to be more active and energetic – more inclusive, governing better, being seen by the people as a positive force for stability and the delivery of services, and security. Shabaab has only delivered an authoritarian and draconian alternative –ruthless, brutal, and bloody.

There are those who argue for "constructive disengagement", like Bronwyn Bruton in a Council on Foreign Relations report, saying "doing less is better than doing harm". Is it possible that the current U.S. approach is doing more harm than good?

Also there are reports of child soldiers being used by the Transitional Federal Government, of civilians being targeted. What does that say about the policy?

I think that's a false dichotomy. I think you can do more without doing harm, and I think that it is up to diplomats and to development workers and to security officials to calibrate U.S. policies in a fashion designed to advance stability, security, and service delivery as well as more inclusiveness and better governance – without doing harm.

I've seen the news reports about allegations of the TFG using child soldiers, and I believe those stories are an exaggeration. Not that there aren't child soldiers around, but that they represent a small fraction of what is happening. When we have talked to and worked with the TFG on training, we have made sure that none of the individuals associated with any training that we have assisted in funding have had child soldiers. It's against our laws. We vet to make sure that we are not in any way supporting child soldiers, and that we are not supporting in any way individuals who have been in violation of someone else's human rights or civil liberties. We take those legal requirements very seriously. Clearly, there are things in Somalia that we can't control, but we certainly try to make sure that anything we're associated with is done legally.

We've also seen in the Washington Post allegations of indiscriminate fire by Amisom troops on civilians. We don't deny that some of this has probably happened, but I do not believe that there is a policy of deliberate shelling by Amisom forces. That some of it may occur, yes, and it's wrong whether it's a lot or a little. But I don't think it represents a policy. Somalia is probably one of the three or four most dangerous and unpredictable war zones in the world, and these kinds of things happen in those environments.

Does the United States provide support directly to the TFG and to the African Union as well?

We work with the TFG directly, and we also work with Amisom countries. We have supported the acquisition of non-lethal equipment by Burundi and Uganda. We have provided them with military equipment – everything from communications gear to uniforms. We have supported the training of TFG forces outside Somalia, mostly in Uganda and in Djibouti. We have supported specialized training in dealing with improvised explosive devices and training for the protection of ports and airports. But this training has been provided by Ugandans, not by any U.S. military officials.

We work with the AU, and we work with the IGAD countries. And that is precisely what we need to do. We encourage others in the international community to do as we are doing. We have not done enough on Somalia, which, for far too long, has been the subject of benign neglect by the United States, and by the international community.

Given the magnitude of the problems on three levels – domestic, regional, international – now is the time for the international community to recognize that this problem will only get worse for all of us if we do not come together to find a solution.

Part 1: Carson Says U.S. is Boosting Efforts to Back Peace in Sudan

EARLIER ALLAFRICA INTERVIEWS

Carson Cites 'Powerful Success Stories' and Reiterates U.S. Commitment to Political and Economic Progress